In late 2019, a mysterious illness began appearing in Wuhan, a city in central China. At first, it seemed like a cluster of pneumonia cases, perhaps something seasonal or a localized outbreak. But within weeks, the world began to realize that something far more dangerous was unfolding. By early 2020, countries across the globe were scrambling to shut borders, cancel flights, and lock down cities. Hospitals overflowed. Streets fell eerily silent. Economies halted. A virus had emerged that would not only claim millions of lives but also challenge the very fabric of modern civilization. Its name was COVID-19.

COVID-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, became the defining global crisis of the 21st century. It was more than just a disease; it was a test of public health systems, scientific progress, political leadership, and global solidarity. But what exactly is COVID-19? How does it work? Why did it spread so quickly? And what has science done to fight back?

This comprehensive exploration delves into the biology, history, symptoms, spread, and global impact of COVID-19. It also chronicles the scientific race to understand, treat, and vaccinate against it—and how it may forever reshape the future of medicine, society, and human behavior.

The Origins of COVID-19: From Animal to Human

The story of COVID-19 begins with a virus. Coronaviruses are a family of viruses known for their crown-like appearance under an electron microscope. They have been responsible for illnesses in humans for decades, often causing mild respiratory infections like the common cold. However, certain coronaviruses that emerge from animal reservoirs can be far more dangerous. This is what scientists call a zoonotic spillover—when a virus jumps from animals to humans.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, is believed to have originated in bats, which are known hosts for various coronaviruses. The virus likely passed through an intermediate animal species before infecting humans. Though the exact pathway remains under investigation, the virus was first identified in Wuhan, China, where a cluster of pneumonia cases was linked to a seafood and live animal market.

The genetic structure of SARS-CoV-2 showed it was a new, previously unknown virus to science. Within weeks of its discovery in December 2019, Chinese scientists sequenced its genome and shared it globally—a crucial step that allowed the development of diagnostic tests and laid the foundation for vaccine research.

What Is SARS-CoV-2? Understanding the Virus Behind the Pandemic

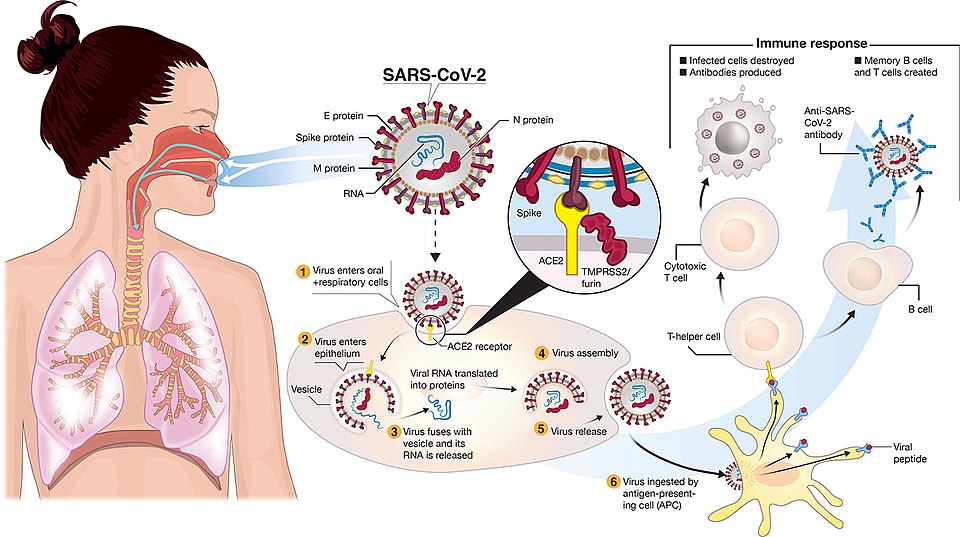

SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the betacoronavirus genus. Like all coronaviruses, it is enclosed in a lipid membrane and contains spike proteins on its surface that give it its characteristic “crown” appearance. These spike proteins are not just decorative—they are the key to the virus’s ability to infect cells.

The spike (S) protein binds to a receptor on human cells known as ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2), which is found in various tissues, including the lungs, heart, intestines, and even blood vessels. Once attached, the virus fuses with the cell membrane, hijacks the cell’s machinery, and begins replicating its RNA and producing viral proteins. Infected cells release new viruses, which go on to infect neighboring cells, triggering an immune response.

One of the features that made SARS-CoV-2 so successful was its ability to spread before symptoms appeared, a trait that made early containment extremely difficult. Some people carried and transmitted the virus while feeling completely healthy. This silent spreader phenomenon contributed to its rapid global transmission.

The Clinical Face of COVID-19: Symptoms, Severity, and Complications

COVID-19 manifests across a wide spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic or mild symptoms to severe respiratory failure and death. The most common symptoms include fever, dry cough, fatigue, and loss of taste or smell. Some patients experience sore throat, diarrhea, body aches, and nasal congestion. In severe cases, COVID-19 leads to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and blood clotting disorders.

The variability in symptoms is striking. While many people recover within two weeks, others require hospitalization, oxygen support, or intensive care. Older adults and those with underlying health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, or cardiovascular disease are at greater risk of severe outcomes.

Complications of COVID-19 have included heart inflammation, stroke, long-term lung damage, kidney injury, and neurological effects. One of the most concerning aspects of the disease is “Long COVID” or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). This condition involves lingering symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, breathlessness, and depression that can persist for months after the initial illness.

Global Spread: From Epidemic to Pandemic

What began as a local outbreak in China rapidly evolved into a global catastrophe. By January 2020, cases were appearing in Thailand, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

Global travel and urban density accelerated the spread. Despite lockdowns, border controls, and social distancing, the virus moved with breathtaking speed. Europe became the epicenter in early 2020, followed by devastating waves in the United States, Latin America, India, and Africa. Hospitals were overwhelmed, and morgues ran out of space. Health systems strained under the pressure of treating thousands of patients simultaneously.

Governments responded with varying degrees of success. Countries like New Zealand, South Korea, and Taiwan managed early containment through aggressive testing, contact tracing, and strict quarantine measures. Others, such as the U.S., Brazil, and India, struggled with fragmented healthcare systems, delayed responses, and public resistance to containment measures.

Testing and Diagnosis: Unveiling the Invisible

Testing became the frontline defense against COVID-19. The gold standard diagnostic method was the reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, which detects viral RNA in a patient’s respiratory sample. Rapid antigen tests and antibody tests were also developed, though they varied in accuracy.

Mass testing enabled health authorities to identify infected individuals, trace contacts, and break chains of transmission. However, early shortages of testing kits and delays in results hampered containment efforts. Over time, testing capacity increased, and home-based rapid tests became widely available, empowering individuals to monitor their own infection status.

The Race for a Vaccine: Science in Overdrive

Perhaps the most inspiring chapter of the COVID-19 story is the global scientific effort to develop a vaccine. Leveraging decades of research on viruses and novel vaccine platforms, scientists raced to create, test, and distribute vaccines at record speed. Within a year of the pandemic’s start, multiple vaccines had completed clinical trials and received emergency use authorization.

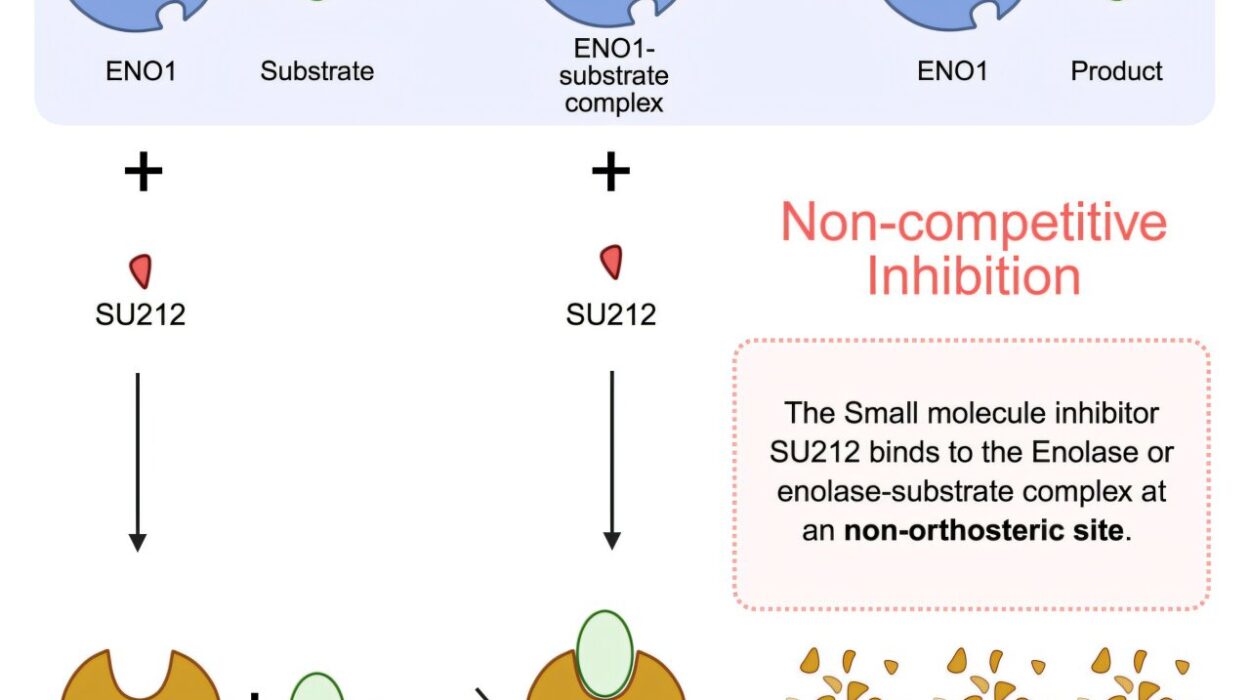

Two of the earliest and most successful vaccines—Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—used messenger RNA (mRNA) technology. These vaccines introduced a piece of genetic code that instructed human cells to produce the spike protein, teaching the immune system to recognize and attack the virus. Other vaccines, such as those from AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Sputnik V, used viral vectors to deliver the spike gene.

Vaccines saved millions of lives, dramatically reducing severe illness and hospitalization. However, challenges emerged. Misinformation, vaccine hesitancy, and inequitable distribution slowed global uptake. Booster doses became necessary as immunity waned and new variants emerged. Yet, the success of mRNA technology opened a new era for vaccine development, with implications far beyond COVID-19.

Variants: The Virus Evolves

Viruses mutate as they replicate. Some mutations offer advantages such as increased transmissibility or immune escape. SARS-CoV-2 followed this evolutionary path, spawning multiple variants that periodically reignited surges in infection.

The Alpha variant, first detected in the UK, was more contagious than the original strain. Delta, first seen in India, caused the most severe global wave, leading to higher rates of hospitalization and death. Omicron, detected in South Africa in late 2021, was even more transmissible but caused milder disease, especially in vaccinated individuals. Its subvariants continued to evolve, challenging the durability of immunity and the effectiveness of vaccines.

Variant surveillance became essential, requiring genomic sequencing and international collaboration. Scientists continued to modify vaccines and explore universal coronavirus vaccines to combat future threats.

Public Health Measures: Masks, Lockdowns, and Mandates

In the absence of vaccines during the early months, non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) became the primary defense. Masks, physical distancing, hand hygiene, and lockdowns were implemented to slow the virus’s spread and buy time for healthcare systems.

These measures were effective but controversial. Lockdowns saved lives but disrupted economies, education, and mental health. Mask mandates became politicized, especially in Western democracies. The tension between individual freedoms and collective safety played out in protests, courtrooms, and policy debates.

Nevertheless, countries that implemented early and coordinated NPIs generally fared better in terms of mortality and healthcare burden. The pandemic exposed weaknesses in public health infrastructure, the importance of clear communication, and the need for global cooperation.

The Societal Impact: A Changed World

COVID-19 left an indelible mark on society. Millions died. Countless more lost loved ones, jobs, or homes. Mental health deteriorated under the weight of isolation, anxiety, and grief. Children missed years of education. Essential workers bore the brunt of the crisis while often receiving the least protection.

Economically, the pandemic triggered recessions, disrupted supply chains, and redefined work. Remote work and telemedicine became mainstream. E-commerce surged. Cities emptied out while suburban and rural areas grew. In many ways, COVID-19 accelerated trends that were already underway.

Politically, the pandemic tested governments, exposed misinformation, and deepened social divides. Trust in science and institutions fluctuated, and conspiracy theories flourished online. Yet, it also inspired acts of heroism, community solidarity, and scientific breakthroughs.

Global Inequity: The Vaccine Divide

One of the harshest lessons of the pandemic was the inequality in global healthcare. While wealthy nations secured vaccines for their populations, many low-income countries struggled to vaccinate even their frontline workers. COVAX, a global initiative to promote equitable access, faced logistical and funding challenges.

This disparity prolonged the pandemic, allowing the virus to circulate and mutate in under-vaccinated regions. It also raised ethical questions about fairness, responsibility, and global solidarity. The pandemic made it painfully clear that no one is safe until everyone is safe.

COVID-19 and the Future: Preparing for the Next Pandemic

As the acute phase of the pandemic receded, attention turned to the future. How can the world prevent the next pandemic? Lessons from COVID-19 emphasize the need for early detection, robust surveillance, stockpiles of protective equipment, flexible manufacturing for vaccines, and investment in public health systems.

Organizations and governments are developing pandemic preparedness plans, strengthening laboratories, and exploring universal vaccine platforms. One proposal is a “pandemic treaty” to facilitate information sharing and joint responses to health threats.

COVID-19 also forced a reevaluation of the relationship between humans and nature. Zoonotic diseases are likely to increase due to deforestation, climate change, and wildlife trade. Preventing future pandemics will require not just medical preparedness but ecological responsibility.

Conclusion: A Pandemic That Redefined the 21st Century

COVID-19 was not just a health crisis—it was a historical rupture, a moment when the world paused, suffered, adapted, and learned. It revealed our vulnerabilities but also our resilience. It showed the power of science, the fragility of systems, and the interconnectedness of all people on this planet.

Understanding what COVID-19 is goes beyond virology or epidemiology. It encompasses sociology, psychology, economics, politics, and ethics. The virus reshaped how we live, work, and connect. It also left us with a choice: to return to business as usual or to build a more prepared, equitable, and compassionate world.

As scientists continue to study the long-term effects of the virus, develop better vaccines, and monitor emerging threats, the legacy of COVID-19 will be written not only in the history books but in the collective consciousness of generations to come.