In the sunbaked badlands of Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, scientists have uncovered the remains of a previously unknown reptile unlike anything seen before. The animal, named Akidostropheus oligos, lived about 220 million years ago during the Late Triassic Period and stood out with an unusual feature: a sharp bony spike projecting upward from its backbone, possibly used as a defensive weapon.

The discovery, published in Palaeodiversity, adds a surprising new branch to the family tree of tanystropheids, a group of long-necked reptiles that once thrived alongside the ancestors of crocodiles, dinosaurs, and birds. These creatures, known for their bizarre body proportions and ecological diversity, are helping paleontologists unravel how reptile life diversified after Earth’s greatest extinction event.

The Archosauromorph Legacy

Akidostropheus belonged to the archosauromorphs, an expansive reptile lineage that originated in the Permian Period, more than 250 million years ago. Following the catastrophic end-Permian extinction—the deadliest event in Earth’s history—archosauromorphs radiated widely, giving rise to crocodiles, non-avian dinosaurs, and ultimately birds.

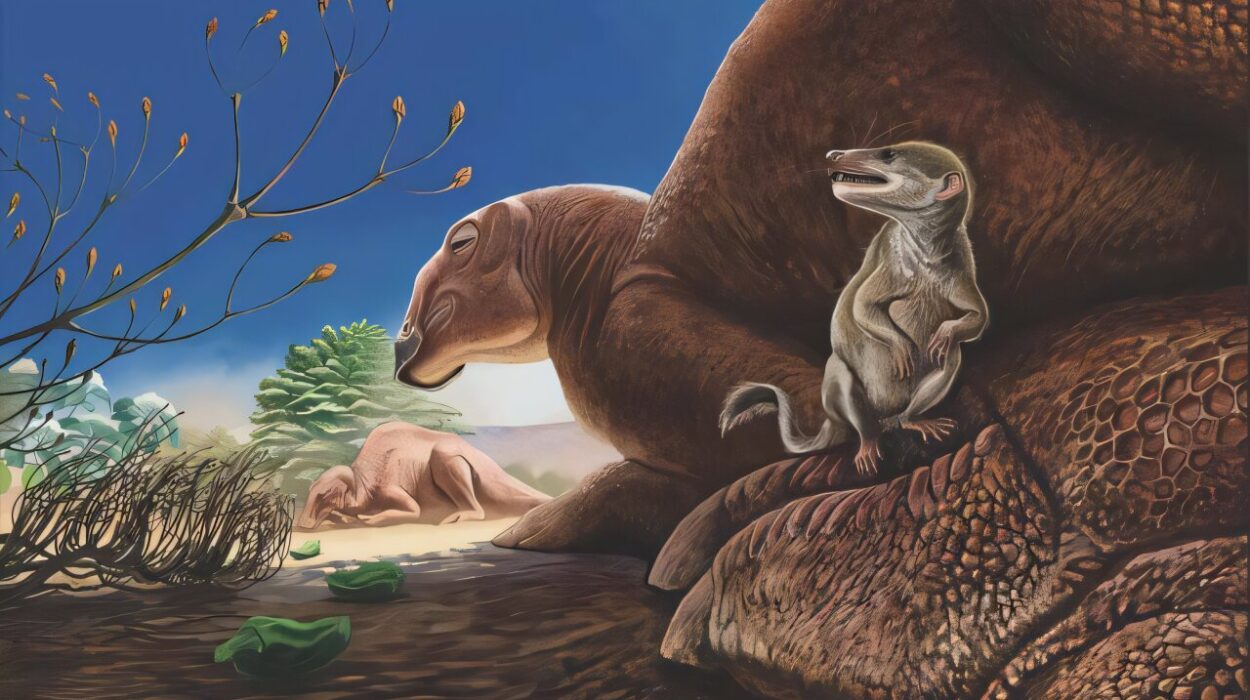

Yet, before these charismatic groups took over the Mesozoic, the so-called “stem” archosauromorphs, like tanystropheids, experimented with strange anatomies and lifestyles. These animals are crucial for understanding both the early steps toward archosaurs and the ecological dynamics of Triassic ecosystems.

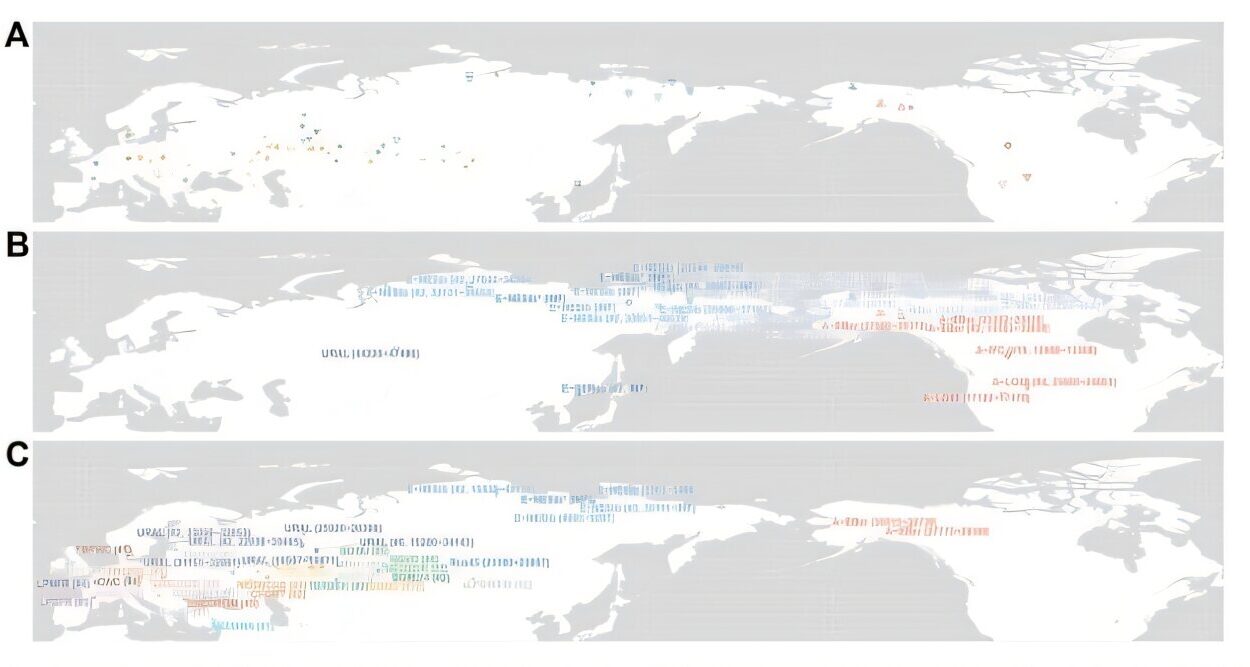

Tanystropheids in particular were evolutionary oddities. Some, like the iconic Tanystropheus, grew necks three times the length of their bodies, while others adapted to aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyles. Until recently, most tanystropheid fossils came from Europe and Asia, leaving their North American record sparse. The new finds in Arizona change that picture dramatically.

A Fossil Treasure at Thunderstorm Ridge

The team’s fieldwork focused on Thunderstorm Ridge, a fossil-rich outcrop within the Blue Mesa Member of the Chinle Formation. The sediments here, deposited between 223 and 218 million years ago, have preserved a jumble of reptile remains. Hundreds of bones—broken, disarticulated, and scattered—were recovered through painstaking excavation.

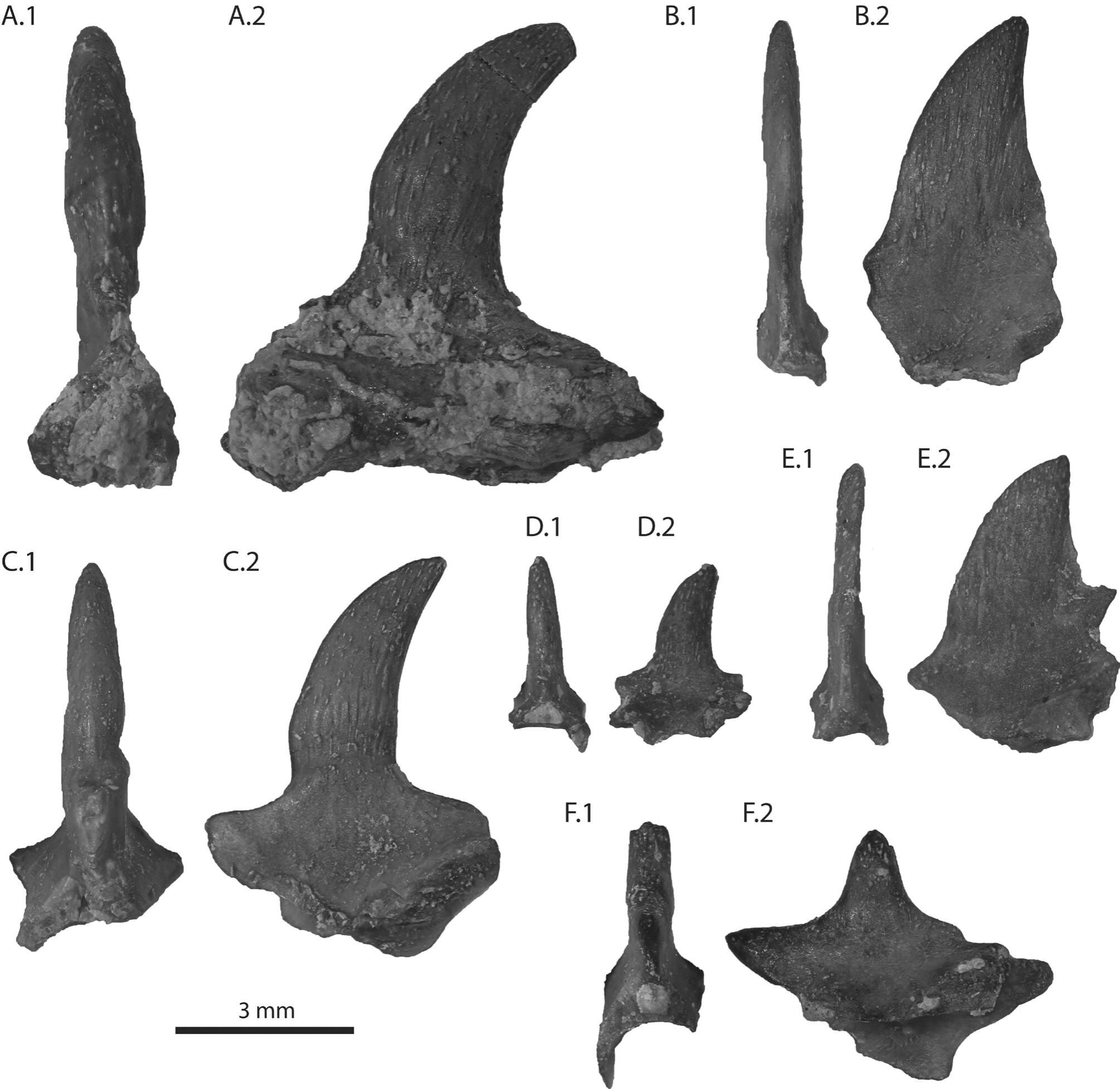

“Collecting these fossils is a slow, meticulous process,” the authors noted. The bones were unearthed by hand quarrying, screenwashing, and even microscopic picking, followed by careful preparation with adhesives, air scribes, and pin vises. What emerged was a remarkable variety of neck vertebrae, each revealing different anatomical blueprints.

By focusing on these cervical bones—key diagnostic structures in archosauromorphs—the researchers identified three distinct tanystropheid taxa. These included an animal resembling Tanystropheus, a pair of unidentified morphotypes, and the brand-new species Akidostropheus oligos.

The Spiked Stranger

What set A. oligos apart was the autapomorphic spike—a bony projection rising from the neural spine of its vertebrae. Measuring just millimeters across (6.7 mm tall and 5.5 mm long in one specimen), these tiny bones nonetheless carried unmistakable evidence of ornamentation. Fine striations suggested the spike may have been covered by a keratinous sheath, much like horns or spines in modern reptiles.

Similar structures were found not only on the neck vertebrae but also along the trunk and tail, hinting at a continuous line of defensive spikes running down its back. The researchers suggest the most likely function of these spikes was defense against predators, making A. oligos one of the earliest reptiles to weaponize its skeleton in this way.

A Cast of Long-Necked Characters

Alongside A. oligos, the site yielded evidence of two other tanystropheid forms.

One morphotype showed moderately elongated vertebrae with shallow ridges and small pits, while another displayed very elongated neck bones with faint side ridges and a keel toward the rear. Together, they hinted at reptiles experimenting with different ways to stretch and strengthen their necks.

The third taxon, closely related to Tanystropheus, bore ultra-elongated vertebrae with deep grooves running along the underside. What’s striking is the dating: these fossils are 4 to 19 million years younger than previously known Tanystropheus specimens, extending the animal’s evolutionary timeline into a later chapter of the Triassic.

Evolution in a Semi-Tropical World

The diversity found at Thunderstorm Ridge paints a picture of Late Triassic ecosystems teeming with evolutionary experimentation. Far from the coastal or lagoonal settings where tanystropheids are often discovered, these fossils come from semi-tropical, inland floodplains, suggesting these reptiles were more adaptable than once thought.

The coexistence of multiple closely related taxa at the same site hints at niche partitioning—different species occupying specialized roles to reduce competition. Some may have been aquatic ambushers, others terrestrial insect-hunters or small vertebrate predators. The presence of spiked defenses in A. oligos shows yet another survival strategy at play.

Rewriting the Story of the Triassic

The study does more than introduce a new species—it challenges assumptions about how diverse and widespread tanystropheids were. By expanding the North American fossil record and providing rare three-dimensional anatomical data, these discoveries help fill gaps in our understanding of early reptile evolution.

The Triassic Period, once overshadowed by the grandeur of the Jurassic dinosaurs, is now recognized as a critical time of innovation and radiation. Creatures like Akidostropheus oligos reveal that the evolutionary stage was crowded with strange experiments—some successful, others evolutionary dead ends.

The Legacy of Akidostropheus

At just a few centimeters long, the bones of A. oligos may seem insignificant. Yet, they carry an outsized message: evolution’s creativity often works on small scales before reshaping the larger world. The spikes that adorned this reptile’s back tell a story of adaptation, defense, and survival in a landscape where predation was a constant threat.

By uncovering this peculiar creature, scientists not only add a new genus and species to the fossil record but also highlight the importance of patient, meticulous paleontology. Each grain of rock sifted, each fragment cleaned under a microscope, brings us closer to understanding how life on Earth recovered, diversified, and flourished after catastrophe.

The discovery of Akidostropheus oligos reminds us that the Triassic world was filled with more than the ancestors of dinosaurs. It was a time of wonder, innovation, and strange reptilian forms—creatures that may have been forgotten by time, but are now rediscovered to expand the story of life’s resilience.

More information: Alaska N. Schubul et al, A diverse assemblage of tanystropheid archosauromorphs from the continental interior of Late Triassic Pangea includes a new taxon (Akidostropheus oligos gen. et sp. nov.), Palaeodiversity (2025). DOI: 10.18476/pale.v18.a5