For millions of people across the world, the simple act of laughing, coughing, or sneezing carries a secret fear—the sudden and uncontrollable loss of urine. This condition, known as urinary incontinence, is often shrouded in silence, cloaked in embarrassment, and dismissed as something to “just live with.” Yet behind that silence are real people—women, men, young mothers, older adults, athletes—whose quality of life is affected by something deeply personal.

Urinary incontinence is not a rare occurrence, nor is it a sign of weakness. It is a medical condition that can be understood, treated, and improved. At the heart of this condition lies a system of muscles we often overlook: the pelvic floor. Strengthening this hidden foundation of the body can restore control, rebuild confidence, and transform daily life. The most famous exercise for this? Kegels. But the truth is, most people do them incorrectly—or without fully understanding the power of the pelvic floor.

This article dives into the science of urinary incontinence, the anatomy of the pelvic floor, and how to truly master pelvic floor training. Along the way, we’ll dispel myths, provide practical guidance, and uncover the emotional impact of regaining control over one’s body.

Understanding Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence is not a single condition but a group of related problems where the bladder’s ability to store or control urine is compromised. It ranges from occasional leaks to a constant loss of bladder control. For some, it means a small drip when exercising; for others, it means avoiding social outings for fear of accidents.

The most common types include:

- Stress incontinence: Leakage triggered by pressure on the bladder, such as coughing, sneezing, laughing, or exercising. This is often linked to weakened pelvic floor muscles.

- Urge incontinence: A sudden, intense need to urinate followed by involuntary loss of urine, often connected to overactive bladder signals.

- Mixed incontinence: A combination of stress and urge incontinence.

- Overflow incontinence: When the bladder doesn’t empty properly, leading to continuous dribbling.

Though it affects both men and women, urinary incontinence is more common in women, largely due to pregnancy, childbirth, and hormonal changes during menopause. However, men—particularly those who have undergone prostate surgery—also face this challenge.

The Emotional Weight of Incontinence

Living with urinary incontinence often goes far beyond the physical inconvenience. It carries a heavy emotional and social burden. Many people describe feelings of shame, anxiety, and loss of dignity. Simple daily activities—running errands, attending a social event, or going to the gym—can trigger overwhelming worry about leaks.

This silent struggle fosters isolation. Some withdraw from friendships, intimacy, or professional opportunities. Depression and low self-esteem are common companions. Yet, the most painful aspect is often the belief that nothing can be done.

The truth is, urinary incontinence is treatable. And one of the most effective tools does not require surgery or medication but rather the empowerment of the body’s own muscular system—the pelvic floor.

The Pelvic Floor: The Body’s Hidden Foundation

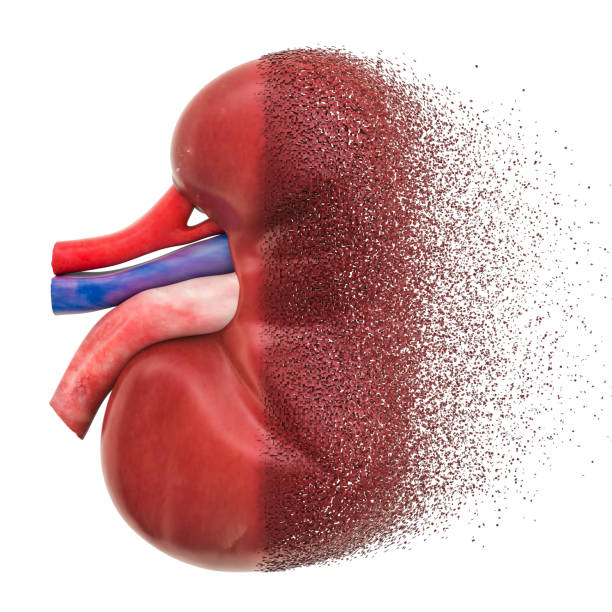

The pelvic floor is a hammock-like group of muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues stretching from the pubic bone at the front to the tailbone at the back. It acts as a supportive sling for key organs: the bladder, uterus (in women), and rectum.

This hidden muscle group has three critical jobs:

- Support: It holds the pelvic organs in place, preventing them from sagging or prolapsing.

- Control: It regulates the openings of the urethra, vagina (in women), and anus, allowing us to consciously start and stop urination, bowel movements, and even play a role in sexual function.

- Stability: It works in harmony with core muscles to stabilize the spine and pelvis, impacting posture and movement.

When the pelvic floor is strong and well-coordinated, it provides reliable control. When it weakens—through childbirth, aging, obesity, chronic coughing, or heavy lifting—the result is often leakage, discomfort, or even pelvic organ prolapse.

Why Kegels Became Famous

In the 1940s, gynecologist Dr. Arnold Kegel introduced pelvic floor exercises as a way to help women struggling with incontinence and postpartum recovery. These contractions, now universally called “Kegels,” were revolutionary: a non-surgical, accessible method to strengthen the muscles that govern bladder control.

The beauty of Kegels lies in their simplicity: contracting and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles, much like squeezing and releasing an internal fist. Over time, consistent practice improves muscle tone and endurance, much like weightlifting strengthens biceps or squats strengthen thighs.

However, Kegels are also widely misunderstood. Many people perform them incorrectly, activating the wrong muscles or holding their breath. Others overdo them, creating tension instead of strength. Done right, they are transformative. Done wrong, they can be frustrating or even harmful.

The Science of Pelvic Floor Training

Just like any other muscle in the body, the pelvic floor responds to training. But unlike visible muscles, its progress is subtle and internal. That’s why awareness is the first step.

The science of muscle physiology applies here too:

- Strengthening fibers: Slow, controlled contractions build endurance, crucial for holding urine during daily activities.

- Fast-twitch fibers: Quick squeezes train the muscles to respond instantly to sudden pressure, like a sneeze.

- Coordination: The ability to relax is just as important as contracting, especially for complete bladder emptying.

Research consistently shows that pelvic floor muscle training reduces urinary incontinence, particularly stress incontinence, with significant improvements after just 8–12 weeks of consistent practice.

Finding the Right Muscles

One of the greatest challenges is simply locating the pelvic floor muscles. Unlike arms or legs, they are not visible, and many people mistakenly engage abdominal or glute muscles instead.

The simplest way to find them is during urination: attempting to stop the flow midstream (though this should not be done regularly, as it can interfere with normal bladder emptying). That sensation—lifting and squeezing internally—is the pelvic floor at work.

Another way is to imagine holding back gas or gently lifting something inside the pelvis without tightening the stomach, thighs, or buttocks.

Doing Kegels Correctly

A proper Kegel has three phases:

- Engage: Gently contract and lift the pelvic floor muscles, as though drawing them upward inside the body.

- Hold: Maintain the contraction for a few seconds without straining or holding your breath.

- Release: Let go completely, allowing the muscles to relax fully.

Breathing plays a critical role—inhale to relax, exhale as you contract. The goal is control, not brute force.

Over time, a routine should include both slow holds (building endurance) and quick squeezes (training rapid response). Consistency matters more than intensity. Just a few minutes a day can lead to meaningful improvements.

When Kegels Alone Aren’t Enough

Though highly effective, Kegels are not a cure-all. For some, the problem lies not only in weakness but also in muscle tension, poor coordination, or nerve damage. Overactive pelvic floor muscles, for example, can actually worsen symptoms.

That’s why professional guidance is often invaluable. Pelvic floor physical therapists specialize in assessing these muscles through gentle examinations, biofeedback, or electrical stimulation, then tailoring programs to individual needs.

Beyond Kegels: Other Pelvic Floor Exercises

The pelvic floor doesn’t work in isolation; it’s part of the body’s core system. Exercises that engage multiple muscle groups can also enhance pelvic strength. Yoga poses like bridge or child’s pose, Pilates-based core training, and even deep breathing exercises improve pelvic health.

Squats, when done with awareness, also activate the pelvic floor. The principle is integration: training the pelvic floor to coordinate with the diaphragm, abdominal muscles, and back muscles for full-body stability.

Lifestyle Factors That Influence Incontinence

Exercise is powerful, but lifestyle choices also shape pelvic health. Excess weight adds pressure on the bladder. Chronic constipation strains the pelvic floor. Coughing from smoking weakens it over time. High-impact sports can aggravate leaks.

Simple changes—hydrating wisely, managing weight, reducing caffeine, quitting smoking—can significantly ease symptoms. Even bladder training techniques, like timed voiding or gradually extending the time between urination, help retrain the bladder-brain connection.

Men, Incontinence, and the Pelvic Floor

Though often thought of as a women’s issue, men also benefit from pelvic floor training. In fact, after prostate surgery, pelvic floor exercises are one of the most recommended strategies for regaining bladder control.

For men, the sensation of engaging the pelvic floor often feels like lifting the base of the penis or tightening around the anus. With practice, Kegels can restore urinary control, improve sexual function, and support overall pelvic health.

Postpartum Recovery and the Pelvic Floor

Pregnancy and childbirth place enormous demands on the pelvic floor. Muscles stretch, nerves may be damaged, and connective tissues can weaken. For many women, this leads to postpartum incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse.

Kegels and other pelvic floor exercises are critical in recovery, helping restore strength and function. However, timing and technique matter—too much too soon can be harmful. Gentle activation, guided by healthcare providers, ensures safe rehabilitation.

The Role of Hormones

Hormones, particularly estrogen, influence pelvic health. During menopause, declining estrogen levels can thin the tissues of the urethra and vaginal walls, reducing their ability to resist pressure. This is one reason why incontinence often emerges or worsens later in life.

Pelvic floor exercises remain beneficial at every age, but in some cases, hormone replacement therapy or local estrogen treatments may complement training.

Breaking the Stigma

Perhaps the greatest barrier to addressing urinary incontinence is not biology but stigma. Too many suffer in silence, convinced it is a natural part of aging or something to be ashamed of. Yet incontinence is a medical condition, not a moral failing.

Conversations—between patients and doctors, friends, partners, or communities—are crucial. When the silence is broken, solutions emerge. Pelvic floor therapy, medical treatments, lifestyle changes, and surgical options all exist. But it begins with the courage to speak.

A Future of Innovation

Biology and technology are expanding possibilities for managing incontinence. Biofeedback devices help people visualize pelvic floor activity. Wearable sensors track progress. Electrical stimulation can activate muscles unable to contract voluntarily.

Research into regenerative medicine and stem cell therapy holds future promise. Meanwhile, public health efforts are slowly normalizing conversations about pelvic health, recognizing it as central to overall well-being.

Regaining Control: A Story of Empowerment

Imagine the transformation: from fearing every cough to laughing freely again, from planning every outing around bathroom access to living spontaneously. Regaining bladder control is not just about dry clothes—it is about reclaiming dignity, freedom, and confidence.

Strengthening the pelvic floor is not glamorous. It takes patience, persistence, and sometimes guidance. But it is profoundly empowering. Every contraction is a step toward control, every relaxation a step toward balance, every exercise an investment in one’s quality of life.

Conclusion: Kegels Done Right, Life Lived Fully

Urinary incontinence is not destiny. It is not something one must simply accept. At its root is a system of muscles—the pelvic floor—that, like any other, can be trained, strengthened, and healed.

Doing Kegels correctly, integrating pelvic floor exercises into daily life, and addressing lifestyle and medical factors unlock the possibility of transformation. For women and men, young and old, this simple yet powerful practice offers hope.

Biology gave us a pelvic floor; awareness and action give us the ability to protect it. By breaking the silence, practicing with intention, and embracing pelvic health as essential, we move closer to a future where laughter, movement, and living fully are no longer shadowed by fear of leakage.

The journey begins within—quiet contractions, gentle lifts, consistent practice. Over time, it leads outward, to renewed freedom, dignity, and joy. Because life is too rich, too beautiful, to live in fear of a sneeze.