Timekeeping has always depended on rhythm. From the steady swing of pendulums to the precise flicker of atomic transitions, every clock humanity has built relies on something that repeats, again and again, with unwavering regularity. But what if a system could generate its own rhythm—naturally, persistently, and without constant external prompting?

A new mathematical analysis suggests that such a possibility may not belong to imagination alone. According to research published in Physical Review Letters and led by Ludmila Viotti at the Abdus Salam International Center for Theoretical Physics in Italy, a strange and fascinating class of physical systems called time crystals could one day provide the foundation for remarkably precise quantum clocks.

Unlike conventional designs that must be continuously driven by external energy, these exotic systems may carry their own built-in rhythm. And if that rhythm can be harnessed, it could redefine how precisely we measure time itself.

When Patterns Escape Space and Enter Time

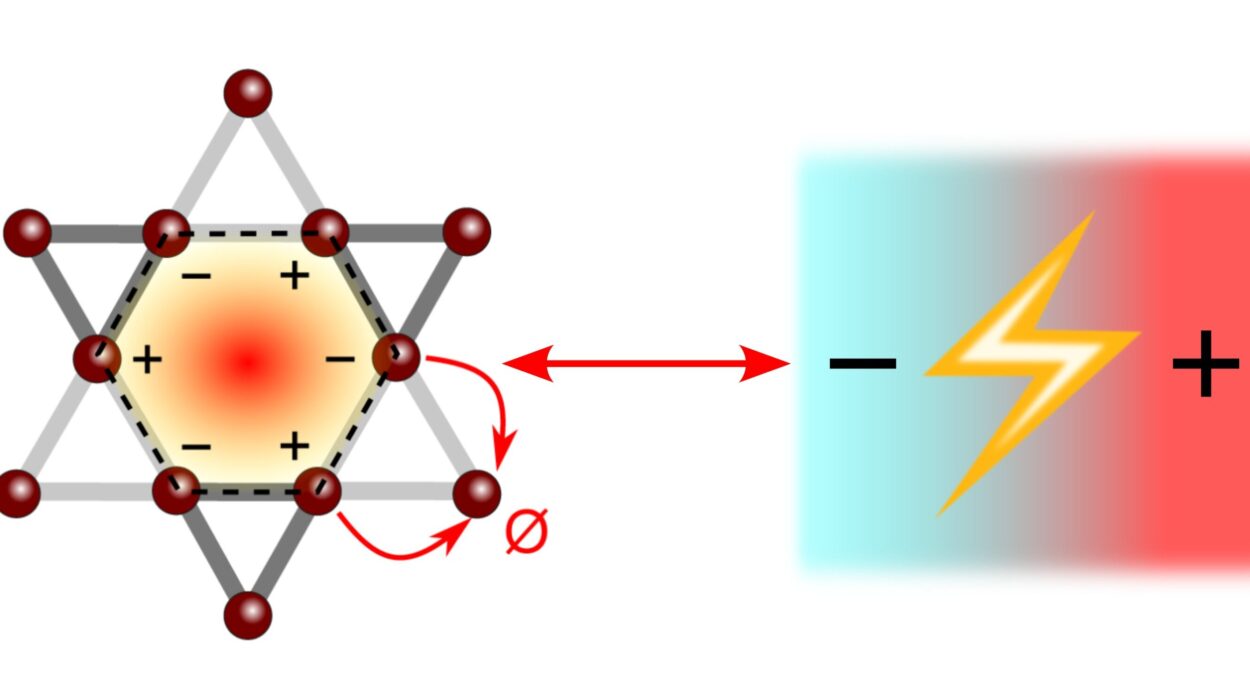

To understand what makes time crystals so intriguing, it helps to begin with a familiar idea. In physics, a crystal is any system whose microscopic structure repeats in a regular pattern. In everyday materials, that pattern repeats across space. The atoms in a crystal lattice, for example, arrange themselves in orderly, repeating positions.

But some systems behave differently. Instead of repeating across space, their configurations repeat across time.

These unusual structures—called time crystals—exhibit patterns that recur again and again as time passes. Their defining feature is not where things are arranged, but how they evolve. A repeating temporal structure replaces the familiar repeating spatial one.

This idea was not merely theoretical speculation. Time crystals were first demonstrated experimentally in 2016, opening a new frontier in physics. Since then, researchers have been trying to understand what these systems might actually be useful for. Could something that repeats naturally in time serve as a perfect timekeeper?

That question lies at the heart of the new research.

The Search for a Truly Reliable Timekeeper

Modern high-precision clocks already operate at astonishing levels of accuracy. Many rely on carefully controlled quantum systems, such as trapped ions or atoms cooled to extremely low temperatures. Lasers push electrons into higher energy states, and when those electrons fall back down, they emit photons with very precise frequencies.

These emitted optical frequencies provide extraordinarily stable reference signals—far more precise than the microwave frequencies used in older atomic clocks. This leap in frequency allows for dramatically improved time measurement.

But there is a trade-off. These systems demand complex setups, continuous energy input, and delicate laboratory conditions. They are powerful, but not simple. Maintaining their precise oscillations requires constant external control.

Time crystals promise something fundamentally different.

Rather than being driven from the outside, a time-crystalline system can sustain its repeating behavior through its own internal interactions. A recurring pattern emerges naturally in a measurable property of the system—a collective observable—and persists without ongoing external excitation.

In other words, the system does not need to be pushed to keep ticking. It simply continues.

If that natural rhythm proves stable enough, it could serve as the heartbeat of an entirely new kind of clock.

A World of Spinning Possibilities

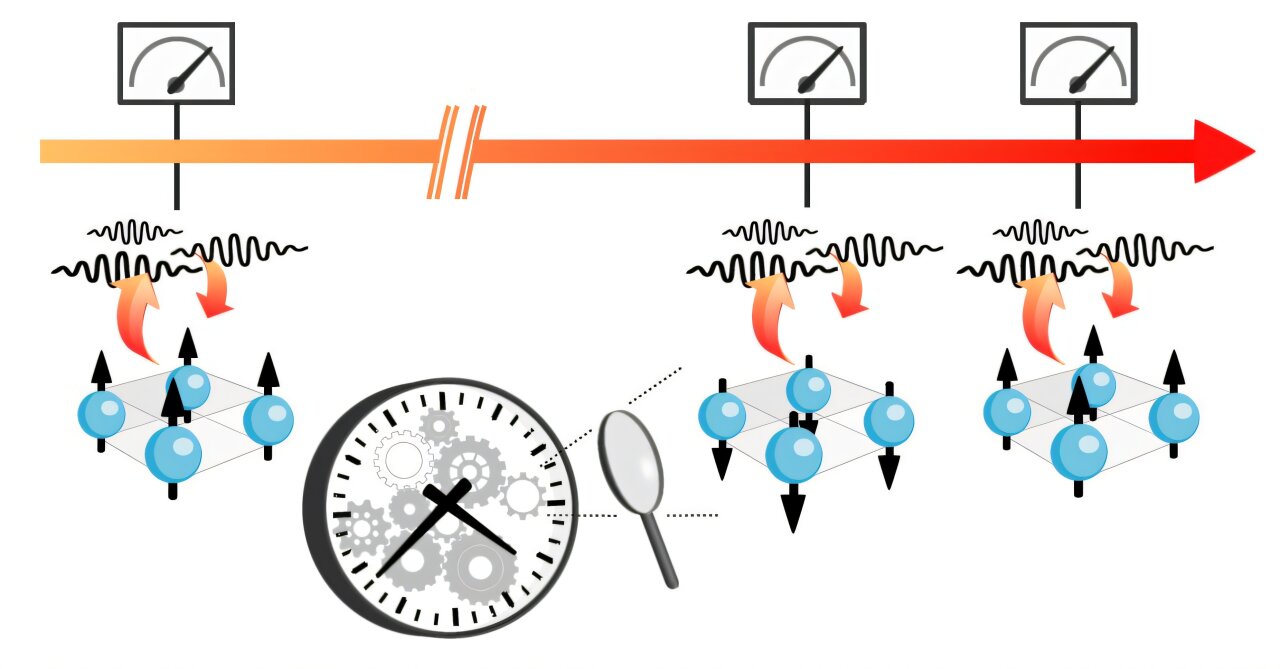

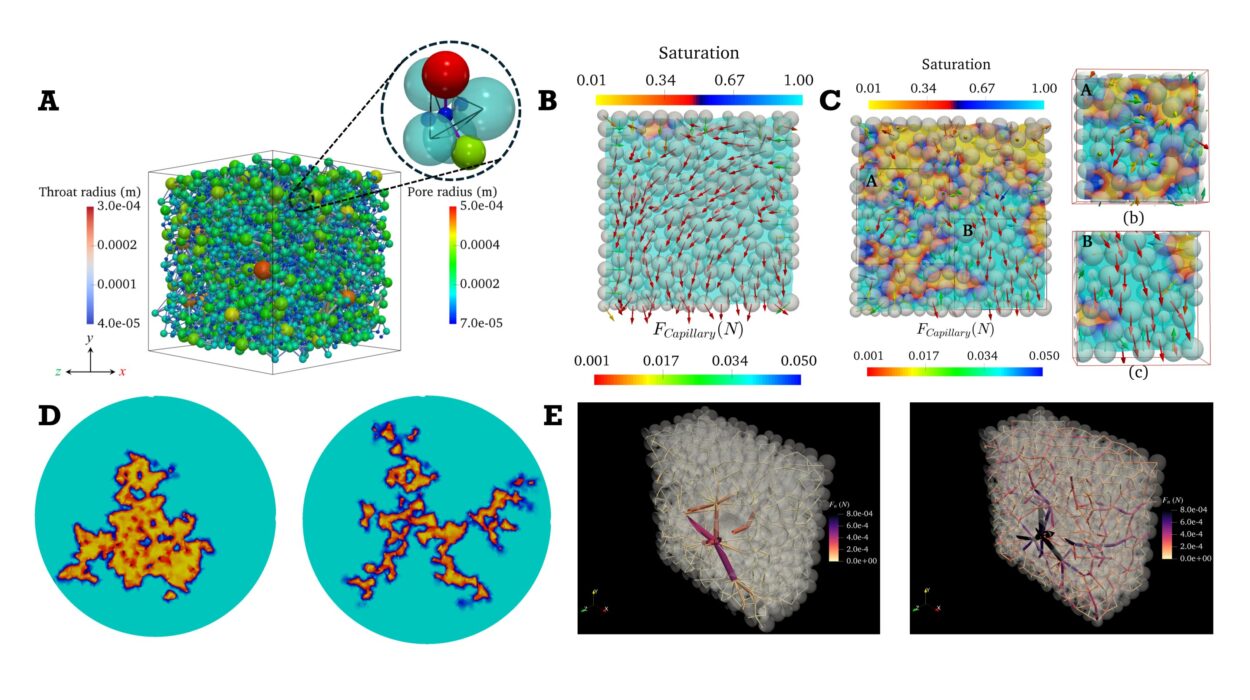

To explore whether this idea could work in practice, Viotti’s team turned to mathematical simulation. They imagined a system made of 100 quantum particles, each capable of existing in one of two possible spin states: up or down.

Even this simple description produces enormous complexity. With so many particles, the number of possible collective spin configurations becomes vast. As the system evolves, these configurations shift according to the internal dynamics governing the particles’ interactions.

Within this simulated world, the researchers observed two distinct behavioral regimes—two different phases of operation.

In one phase, the system behaves conventionally. Its collective spin configuration can be made to oscillate, but only if an external laser field continuously drives the motion. The rhythm exists, but it must be imposed from outside.

In the other phase, something remarkable happens. A repeating pattern emerges spontaneously. The oscillation sustains itself, not because of constant external influence, but because of the system’s own internal structure. This is the time-crystalline phase—a self-maintaining rhythm generated from within.

Both phases produce oscillations. But only one produces them naturally.

The question then becomes: which rhythm keeps better time?

Testing the Limits of Precision

To evaluate timekeeping performance, the researchers asked how well each phase could measure increasingly tiny intervals. The smaller the time slices being measured, the greater the demand on the clock’s precision.

In the conventional phase, where oscillations depend on external driving, precision began to falter as the time intervals shrank. The clock’s ability to resolve fine temporal differences deteriorated quickly.

In the time-crystalline phase, the outcome was strikingly different. Even when probing extremely short time intervals, the system’s precision remained far more stable. Its self-generated oscillations held their integrity under conditions that challenged the externally driven system.

The comparison revealed a key insight. A rhythm sustained by intrinsic interactions may be inherently more robust than one sustained by continuous external forcing.

If confirmed experimentally, this could mark a profound shift in how quantum clocks are designed. Instead of constantly maintaining oscillations from the outside, engineers might someday rely on systems that naturally keep their own tempo.

A Future Still Taking Shape

Despite the promise revealed by the mathematical analysis, practical realization remains a distant goal. Significant technological advances will be required before time crystals can serve as working components in real quantum clocks.

For now, the findings exist primarily as theoretical guidance—a demonstration of what might be possible under the right conditions. Yet even this conceptual step is important. By showing that time-crystalline systems could, in principle, outperform conventional designs in precision, the research provides a roadmap for future experimental exploration.

Viotti and her colleagues hope their work will inspire both theoretical refinement and laboratory testing. Bridging the gap between mathematical possibility and physical implementation will be a long journey, but one with potentially transformative rewards.

Why This Discovery Matters

Time measurement underpins much of modern technology. Systems that depend on precise timing include satellite navigation, which relies on extraordinarily accurate clocks to determine position, and ultra-sensitive detectors of magnetic fields, which require stable temporal references to detect minute changes.

Improving timekeeping precision can therefore ripple across many scientific and technological domains.

The new research suggests that time crystals—once considered purely exotic curiosities—could eventually provide a more stable and efficient foundation for the next generation of quantum clocks. By sustaining oscillations through internal interactions rather than constant external excitation, these systems may offer both enhanced precision and reduced operational complexity.

If future experiments confirm the theoretical predictions, the implications could be profound. Humanity’s ability to measure time—already astonishingly refined—could become even more exact.

And all because of systems that do something quietly extraordinary: they keep ticking on their own.

Study Details

Anonymous, Quantum time crystal clock and its performance, Physical Review Letters (2026). DOI: 10.1103/dj21-gmdj . On arXiv: arxiv.org/abs/2505.08276