In the middle of the twentieth century, long before smartphones, social media, or conversational artificial intelligence, a quiet but radical question was posed: can machines think? The question did not emerge from science fiction or philosophical speculation alone, but from the mind of a mathematician who had already reshaped the modern world. Alan Turing, best known for his foundational work in computation and his role in codebreaking during World War II, understood that asking whether a machine could “think” was both profound and dangerously vague. Words like thinking and intelligence carried too much philosophical baggage. So Turing proposed something deceptively simple: instead of asking what intelligence is, ask whether a machine can convincingly behave like an intelligent human.

From this idea emerged what is now known as the Turing Test. It has become one of the most famous and controversial ideas in the history of artificial intelligence. To some, passing the Turing Test would signal the arrival of truly intelligent machines. To others, it would prove very little beyond a machine’s ability to imitate human conversation. Decades after its proposal, the test still sparks debate, not only about machines, but about ourselves: what intelligence really means, how we recognize it, and whether human-like behavior is the right benchmark at all.

This article explores the Turing Test in depth, examining its origins, its goals, its limitations, and why passing it might not mean that a machine is genuinely “smart.” Along the way, it reveals how the test continues to shape modern discussions about artificial intelligence, consciousness, and the nature of understanding.

Alan Turing and the Problem of Defining Intelligence

Alan Turing lived at a time when the very idea of a computing machine was new and uncertain. Computers as we know them did not exist; computation was largely understood as a human activity involving pencil, paper, and disciplined thought. Turing’s theoretical work helped define what computation itself meant, showing that a simple abstract machine could, in principle, perform any calculation that could be described algorithmically. This insight laid the foundation for digital computers.

When Turing turned his attention to machine intelligence, he quickly encountered a problem that still troubles researchers today. Intelligence is an everyday word, but it resists precise definition. Is intelligence the ability to reason logically, to solve problems, to learn from experience, to use language, or to understand meaning? Humans display all of these abilities, but not always consistently or equally. Even among people, judgments about intelligence are shaped by culture, context, and bias.

Turing recognized that debates about whether machines could think risked becoming endless philosophical arguments over definitions. To avoid this, he reframed the question in operational terms. Instead of asking whether a machine truly thinks, he proposed a practical test based on observable behavior. If a machine’s responses were indistinguishable from a human’s in a particular setting, perhaps that was enough to count as thinking.

This move was both pragmatic and provocative. It shifted the focus away from inner mental states and toward external performance. In doing so, it also raised a deeper question: is intelligence something we infer from behavior, or does it require something more?

The Structure of the Turing Test

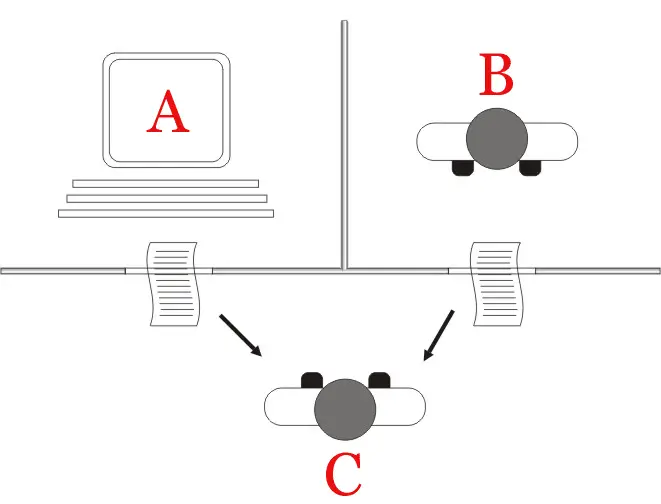

The Turing Test was originally described as an “imitation game.” In its classic form, a human judge engages in a text-based conversation with two unseen participants: one is a human, the other a machine. The judge’s task is to determine which is which, based solely on their written responses. If the judge cannot reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine is said to have passed the test.

Several details of this setup are crucial. The interaction is text-only, eliminating clues such as voice, appearance, or physical presence. This restriction was deliberate, ensuring that success depended on language use rather than sensory mimicry. The judge is free to ask any questions, from casual small talk to complex reasoning puzzles. The machine, in turn, must respond in a way that appears human.

At first glance, the test seems straightforward, even elegant. Language is one of the most distinctive features of human intelligence. It allows us to express abstract ideas, emotions, intentions, and knowledge. A machine that can participate in unrestricted conversation might reasonably be considered intelligent.

Yet embedded within this simplicity are profound assumptions. The test assumes that intelligence can be evaluated through conversational behavior alone. It also assumes that human-like responses are the gold standard for intelligence. These assumptions have been challenged repeatedly, especially as machines have become increasingly capable of generating convincing language without clear evidence of understanding.

Early Reactions and Misunderstandings

When Turing introduced his test, reactions were mixed. Some philosophers and scientists found it compelling, appreciating its clarity and practicality. Others objected strongly, arguing that imitation was a poor substitute for genuine thought. A machine might fool a human judge through clever tricks, scripted responses, or sheer speed, without possessing any real understanding.

Turing anticipated many of these objections. He addressed concerns about consciousness, emotions, creativity, and even spirituality, arguing that human judgments of intelligence are themselves based on behavior. We infer that other people think and feel not because we can access their inner experiences, but because they act in ways similar to us.

Despite these arguments, the Turing Test gradually took on a symbolic role that went beyond Turing’s original intent. It became shorthand for the ultimate goal of artificial intelligence: building machines that are indistinguishable from humans in conversation. This symbolism, while powerful, also contributed to confusion. Passing the Turing Test came to be seen by some as proof of machine intelligence, rather than as one possible indicator among many.

Intelligence as Imitation Versus Intelligence as Understanding

At the heart of the debate over the Turing Test lies a tension between two views of intelligence. One view emphasizes behavior: if a system behaves intelligently, responding appropriately to a wide range of situations, then it is intelligent by definition. The other view emphasizes internal processes: intelligence requires understanding, awareness, or meaningful representation, not just outward performance.

The Turing Test clearly aligns with the behavioral view. It asks whether a machine can produce responses that are functionally equivalent to those of a human. But critics argue that this equivalence may be superficial. A machine might generate correct or convincing answers without any grasp of what those answers mean.

This concern becomes clearer when we consider how modern AI systems operate. Many language-based systems rely on statistical patterns learned from vast amounts of text. They generate responses by predicting which words are likely to come next, given the context. This process can produce remarkably fluent and relevant language, yet it does not necessarily involve understanding in the human sense.

The distinction between imitation and understanding is subtle but important. Humans do not merely produce language; they use it to convey intentions, beliefs, and experiences grounded in a shared physical and social world. Whether a machine that lacks such grounding can truly be said to understand remains an open question.

The Chinese Room Argument and the Limits of the Test

One of the most influential critiques of the Turing Test came from philosopher John Searle, who proposed the famous “Chinese Room” thought experiment. In this scenario, a person who does not understand Chinese is placed in a room with a set of rules for manipulating Chinese symbols. By following these rules, the person can produce appropriate responses to questions written in Chinese, convincing outside observers that the room understands the language.

According to Searle, this situation mirrors what happens in a computer program. The system manipulates symbols according to formal rules, without understanding their meaning. From the outside, the behavior appears intelligent, but internally there is no comprehension. The Chinese Room, Searle argued, could pass a Turing Test in Chinese without understanding a single word.

This argument does not deny that machines can behave intelligently. Instead, it challenges the idea that behavior alone is sufficient to establish understanding. If the Chinese Room passes the Turing Test, does that mean it understands Chinese? Many people intuitively answer no, suggesting that passing the test might not be enough to demonstrate genuine intelligence.

Supporters of the Turing Test respond that understanding itself may be nothing more than the ability to use symbols appropriately within a system. From this perspective, the distinction between syntax and semantics may be less clear-cut than critics assume. The debate remains unresolved, reflecting deeper disagreements about the nature of mind and meaning.

Language as a Proxy for Intelligence

The Turing Test places language at the center of intelligence assessment. This choice reflects the undeniable importance of language in human cognition. Language enables abstract reasoning, social coordination, and cultural transmission. It allows us to ask questions, tell stories, and imagine possibilities beyond immediate experience.

However, equating intelligence with conversational ability has limitations. Many forms of intelligence do not depend primarily on language. Visual perception, motor coordination, spatial reasoning, and emotional understanding are all central to human intelligence, yet they play little role in the classic Turing Test.

Moreover, language itself can be misleading. Humans often use fluent language to express confusion, uncertainty, or even deception. A person can speak eloquently without deep understanding, while another may understand profoundly but struggle to articulate their thoughts. If this is true for humans, it raises questions about using language alone as a measure of intelligence in machines.

The focus on language also encourages AI systems to prioritize surface-level fluency over deeper reasoning or grounding. A machine trained to pass the Turing Test may learn to avoid difficult questions, deflect with humor, or imitate human conversational quirks, all without improving its underlying cognitive abilities.

The Problem of Deception and Performance

Another challenge for the Turing Test is its reliance on deception. To pass, a machine must convince a human judge that it is human. This framing implicitly rewards systems that hide their limitations rather than confront them. A machine that admits ignorance or responds honestly but non-humanly may fail the test, while a machine that uses evasive or misleading tactics may succeed.

This emphasis on performance over transparency raises ethical and practical concerns. In real-world applications, we often want machines to be reliable, explainable, and aware of their own limitations. A system optimized to pass the Turing Test might prioritize appearing competent over being trustworthy.

Furthermore, the test depends heavily on the expectations and biases of human judges. What counts as “human-like” varies across cultures, contexts, and individuals. A machine might pass the test with one judge but fail with another, not because its intelligence has changed, but because human perceptions have.

These issues suggest that passing the Turing Test may say as much about human psychology as it does about machine intelligence.

Modern AI and the Illusion of Understanding

In recent years, advances in machine learning have produced AI systems capable of generating highly convincing text. These systems can answer questions, write essays, and engage in extended dialogue on a wide range of topics. In many interactions, they appear knowledgeable, coherent, and even empathetic.

Such systems bring the Turing Test back into public attention. If a machine can carry on a conversation that feels natural and informative, has it passed the test in spirit, if not in a formal experimental setting? And if so, what does that achievement really mean?

From a scientific perspective, it is important to distinguish between linguistic competence and conceptual understanding. Modern AI systems learn from patterns in data, not from direct experience of the world. They do not have bodies, sensory perception, or personal histories. Their “knowledge” consists of statistical associations rather than grounded concepts.

This does not make their achievements trivial. Generating coherent language at scale is a remarkable technical accomplishment. But it does suggest caution in interpreting conversational success as evidence of human-like intelligence. A machine may produce responses that sound thoughtful without having beliefs, intentions, or awareness.

The emotional impact of interacting with such systems can be powerful. Humans are naturally inclined to attribute minds to entities that communicate fluently. This tendency can lead us to overestimate machine intelligence, projecting understanding where there may be none.

Intelligence Beyond Human Likeness

One of the most significant limitations of the Turing Test is its focus on human imitation. By defining intelligence in terms of resemblance to human behavior, the test risks overlooking other forms of intelligence that are equally valid or even superior in certain domains.

Machines already outperform humans in tasks such as complex calculations, pattern recognition in large datasets, and strategic games with clearly defined rules. These achievements demonstrate intelligence in a functional sense, yet they do not resemble human cognition. A chess-playing program does not think like a human chess master, but it can play at a level no human can match.

If intelligence is the ability to solve problems, adapt to environments, and achieve goals, then human-like conversation is only one expression of it. The Turing Test, by privileging imitation, may encourage a narrow view of intelligence that undervalues diversity in cognitive strategies.

This perspective invites a broader question: should we judge machine intelligence by how well machines mimic us, or by how effectively they perform tasks in their own way? The answer has implications not only for AI research but for how we understand intelligence itself.

Consciousness, Experience, and the Hard Problem

Perhaps the deepest reason why passing the Turing Test might not mean a machine is “smart” lies in the issue of consciousness. Human intelligence is intimately connected to subjective experience: the feeling of thinking, understanding, and being aware. We do not merely process information; we experience the world.

The Turing Test deliberately sidesteps the question of consciousness, focusing instead on observable behavior. Turing himself was skeptical of claims that consciousness could be reliably tested or defined. Yet for many people, intelligence without experience feels incomplete.

A machine could, in principle, pass the Turing Test while lacking any inner life. It could generate responses without feeling confusion, curiosity, or insight. Whether such a system should be considered truly intelligent depends on one’s philosophical stance.

From a scientific standpoint, consciousness remains poorly understood. There is no agreed-upon test for its presence, whether in humans, animals, or machines. This uncertainty makes it difficult to incorporate consciousness into formal criteria for intelligence. The Turing Test avoids this difficulty, but at the cost of leaving a central aspect of intelligence unaddressed.

The Enduring Influence of the Turing Test

Despite its limitations, the Turing Test has had a lasting impact on artificial intelligence research and public imagination. It provided an early, concrete goal that stimulated discussion and experimentation. It also forced researchers to confront the complexity of natural language and human interaction.

The test’s influence extends beyond science into philosophy, literature, and popular culture. It has shaped how people think about intelligent machines, often framing AI progress in terms of conversational ability. Even criticisms of the test have helped clarify important distinctions between appearance and reality, performance and understanding.

In this sense, the Turing Test’s value may lie less in its role as a definitive measure and more in its function as a catalyst for debate. It continues to provoke questions that remain central today: what does it mean to understand, to think, to be intelligent?

Rethinking What It Means to Be “Smart”

If passing the Turing Test does not necessarily mean a machine is smart, then what does? The answer depends on how intelligence is defined. Scientific perspectives increasingly view intelligence as a collection of capacities rather than a single trait. These capacities include learning, reasoning, perception, communication, and adaptation, each of which can be studied and measured in different ways.

From this viewpoint, no single test can capture intelligence in its entirety. The Turing Test assesses one narrow slice of cognitive behavior: conversational imitation. It does not measure problem-solving ability, creativity, emotional understanding, or embodied interaction with the world.

Recognizing these limitations does not diminish the test’s historical importance. Instead, it places it in context, as an early attempt to grapple with a complex and evolving concept. As artificial intelligence advances, the challenge is not merely to build machines that sound human, but to develop systems that are robust, transparent, and aligned with human values.

Conclusion: Beyond the Imitation Game

The Turing Test remains one of the most iconic ideas in the study of artificial intelligence, not because it offers a final answer, but because it raises enduring questions. It challenges us to consider how we recognize intelligence, why we associate it with certain behaviors, and where the boundary lies between imitation and understanding.

Passing the Turing Test might demonstrate remarkable technical skill and linguistic sophistication, but it does not settle the deeper question of what it means for a machine to be “smart.” Intelligence is richer and more complex than conversational fluency alone. It involves understanding, context, learning, and perhaps even experience.

In the end, the most important legacy of the Turing Test may be its reminder that intelligence is not a simple label to be awarded, but a concept to be explored. As machines grow more capable, the test invites us to look inward as well as outward, examining not only what machines can do, but how we define ourselves as thinking beings in a universe increasingly shared with artificial minds.