For more than a century, robots have lived in our collective imagination as hard, angular, metallic beings. From early industrial machines bolted to factory floors to science-fiction androids with gleaming steel limbs, the robot has been defined by rigidity, precision, and strength. These machines were built to be powerful, fast, and repeatable, excelling in environments carefully engineered to suit them. Yet as robotics moves beyond factories and laboratories and into hospitals, homes, oceans, disaster zones, and even the human body, this traditional vision is beginning to fracture. The future of robotics, many researchers now argue, is not hard and metallic but soft, flexible, and adaptive. The future is squishy.

Soft robotics represents a profound shift in how scientists and engineers think about machines, materials, and intelligence. Instead of resisting deformation, soft robots embrace it. Instead of rigid joints and precise motors, they use elastic materials, fluid-driven motion, and structures inspired by living organisms. This change is not merely aesthetic. It reflects a deeper understanding of how nature solves complex problems and how machines must evolve if they are to safely and effectively coexist with the living world.

The Limits of Traditional Robotics

Classical robotics emerged alongside industrialization, shaped by the needs of manufacturing. Assembly lines required machines that could perform repetitive tasks with extreme accuracy and reliability. Rigid metal frames, electric motors, gears, and precise control algorithms were ideal for this environment. These robots excelled at welding car bodies, assembling electronics, and moving heavy loads with millimeter precision. Their strength lay in predictability.

However, rigidity comes at a cost. Traditional robots are inherently fragile in unstructured environments. A slight misalignment, an unexpected obstacle, or a human presence can turn a powerful industrial robot into a dangerous liability. Extensive safety measures, such as cages and emergency shutdown systems, are required to keep humans safe. The robots themselves must rely on complex sensing and control systems to compensate for their lack of physical adaptability.

As roboticists began pushing robots out of factories and into real-world settings, the limitations of rigidity became increasingly clear. Natural environments are messy. Surfaces are uneven, objects vary in shape and texture, and interactions are rarely perfectly predictable. Living organisms handle this complexity effortlessly, not because they calculate everything precisely, but because their bodies are inherently compliant. They bend, stretch, compress, and absorb forces without breaking. This realization has driven a fundamental question: what if robots, too, were built to yield rather than resist?

What Is Soft Robotics?

Soft robotics is a subfield of robotics that focuses on creating machines made primarily from compliant, deformable materials such as silicones, elastomers, gels, fabrics, and even biological tissues. These robots lack the rigid skeletons and discrete joints typical of conventional machines. Instead, their bodies can continuously deform, allowing them to adapt their shape to their surroundings.

Scientifically, soft robotics draws on principles from physics, materials science, biology, and engineering. Soft robots exploit elasticity, viscoelasticity, fluid dynamics, and nonlinear mechanics. Their motion often emerges from the interaction between material properties and external forces rather than from tightly controlled motor commands. This gives them a fundamentally different relationship with the world.

Importantly, softness is not synonymous with weakness. Soft materials can store and release energy, distribute stress, and survive impacts that would damage rigid machines. By allowing deformation, soft robots can interact safely with delicate objects and living beings, opening possibilities that rigid robots struggle to achieve.

Lessons from Living Systems

Nature is the greatest inspiration for soft robotics. Almost all living organisms are soft or at least partially compliant. Even animals with hard skeletons rely on muscles, tendons, skin, and connective tissue that deform constantly. This softness is not a flaw but a feature, enabling adaptability, resilience, and efficiency.

Consider the octopus, one of the most iconic inspirations for soft robotics. With no rigid bones, an octopus can squeeze through tiny openings, manipulate objects with extraordinary dexterity, and regenerate damaged limbs. Its arms act simultaneously as sensors, actuators, and structural supports. Control is distributed throughout the body rather than centralized in a single brain. This challenges the traditional robotics paradigm, which assumes a rigid body controlled by a central processor.

Similarly, worms move by propagating waves of contraction through their soft bodies, allowing them to navigate complex terrain. Jellyfish exploit fluid interactions and elastic recoil to swim efficiently. Human hands, despite containing bones, rely heavily on soft tissues that conform to the shape of objects, enabling delicate manipulation.

Soft robotics seeks to capture these biological advantages not by copying organisms exactly, but by understanding the physical principles that make soft bodies so effective. The result is a new design philosophy where intelligence is embedded not only in software but also in materials and structure.

The Physics of Softness

From a scientific perspective, softness introduces complexity. Rigid bodies are relatively easy to model because their shape does not change. Soft bodies, by contrast, undergo continuous deformation, leading to highly nonlinear behavior. Forces applied at one point can produce unexpected effects elsewhere in the structure.

Soft materials exhibit properties such as elasticity, where they return to their original shape after deformation, and viscoelasticity, where their response depends on time and loading history. These properties allow soft robots to absorb shocks, damp vibrations, and smoothly interact with their environment. However, they also complicate control, as the robot’s shape and mechanical state are constantly changing.

Physicists and engineers studying soft robotics must grapple with continuum mechanics, a branch of physics that describes materials as continuous distributions of matter rather than collections of discrete parts. This contrasts sharply with the rigid-body mechanics traditionally used in robotics. Advances in computational modeling, experimental methods, and materials characterization have been crucial in making soft robotics feasible.

Actuation Without Motors

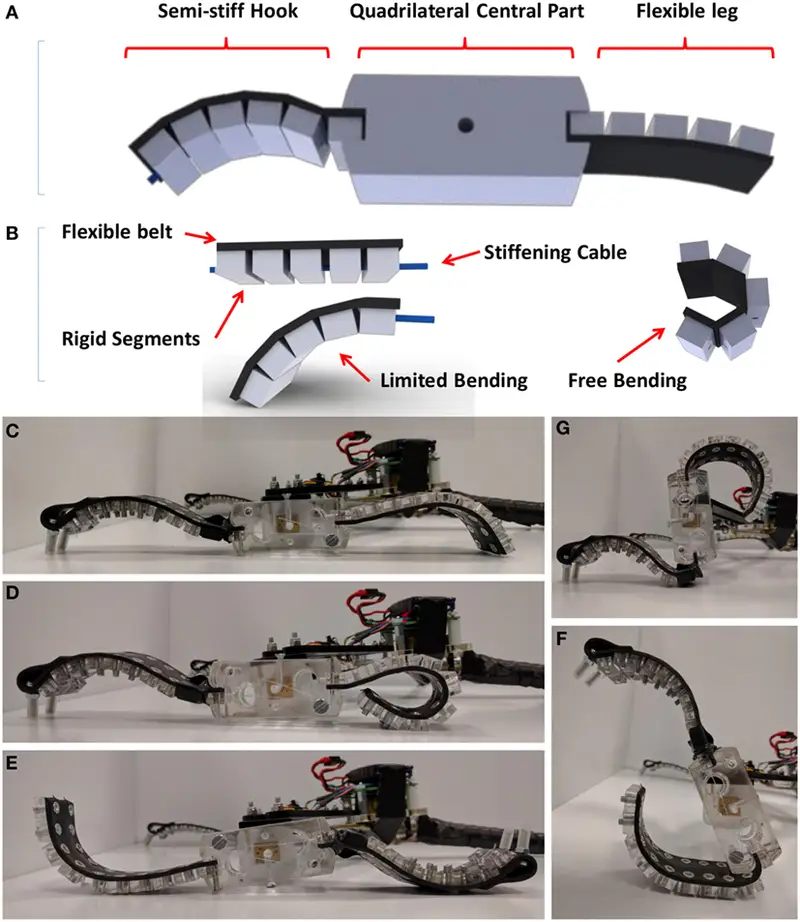

One of the most striking differences between soft robots and traditional machines lies in how they move. Rigid robots typically rely on electric motors or hydraulic actuators connected by joints. Soft robots often use entirely different mechanisms.

Pneumatic and hydraulic actuation is common in soft robotics. By inflating chambers within an elastic material, a robot can bend, twist, or elongate. The direction and extent of motion depend on the geometry of the chambers and the material’s properties. This approach allows smooth, lifelike movement without rigid components.

Other soft robots use smart materials that respond directly to external stimuli. Shape-memory polymers can change shape when heated. Dielectric elastomers deform under electric fields. Hydrogels swell or contract in response to changes in humidity, temperature, or chemical composition. These materials blur the line between actuator and structure, further integrating function into form.

The emotional resonance of this approach is subtle but powerful. Motion in soft robots often appears organic, even gentle. Watching a soft robotic gripper wrap itself around a fragile object can feel less like observing a machine and more like witnessing a living process.

Control in a Deformable World

Controlling a soft robot presents challenges that strike at the heart of robotics and neuroscience. In rigid robots, control algorithms calculate precise joint angles and motor torques. In soft robots, there may be no joints at all, and the number of possible shapes is effectively infinite.

One strategy is to simplify control by exploiting the body’s physical properties. This concept, sometimes called morphological computation, suggests that the robot’s shape and material can perform part of the “computation” traditionally handled by software. For example, a soft leg can passively adapt to uneven ground without requiring complex sensing or control.

Another approach involves distributed sensing and control, inspired by biological systems. Soft sensors made from stretchable materials can be embedded throughout a robot’s body, providing rich information about deformation, pressure, and contact. Machine learning techniques are increasingly used to map this sensory data to control actions, allowing robots to learn how to move and interact through experience rather than explicit programming.

These strategies reflect a broader philosophical shift. Instead of imposing rigid order on the world, soft robotics embraces uncertainty and variability. Control becomes a dialogue between body, environment, and algorithm rather than a top-down command.

Safety and Human Interaction

One of the strongest arguments for soft robotics lies in safety. As robots increasingly work alongside humans, physical interaction becomes unavoidable. Rigid robots, even when carefully controlled, pose risks due to their mass, speed, and stiffness. Collisions can result in serious injury.

Soft robots, by contrast, naturally limit the forces they can exert. Their compliant bodies deform upon contact, reducing impact forces and distributing pressure over a larger area. This makes them inherently safer for tasks such as rehabilitation, caregiving, and collaborative manufacturing.

In medical settings, softness is particularly valuable. Soft robotic devices can conform to the human body, providing assistance without causing discomfort or damage. Wearable exosuits made from textiles and elastomers can support movement without restricting natural motion. Soft surgical tools can navigate delicate tissues with reduced risk of injury.

The emotional dimension of safety should not be underestimated. People are more likely to trust and accept robots that feel safe to touch. Softness changes not only the physical interaction but also the psychological relationship between humans and machines.

Soft Robotics in Medicine

Few fields stand to benefit more from soft robotics than medicine. The human body is itself a soft, dynamic system, and interacting with it using rigid tools is inherently challenging. Soft robotic technologies offer a more harmonious interface.

In minimally invasive surgery, soft robotic instruments can snake through complex anatomical pathways, reaching targets that rigid tools cannot. Their compliance allows them to navigate without exerting excessive force on surrounding tissues. In rehabilitation, soft robotic gloves and suits can assist patients recovering from stroke or injury, providing gentle, adaptive support that responds to the user’s intent.

Soft robots are also being explored for drug delivery, where tiny deformable devices could move through blood vessels or gastrointestinal tracts. While many of these applications remain experimental, they illustrate the profound potential of softness to transform healthcare.

Beyond the technical benefits, there is an emotional aspect to medical soft robotics. Devices that feel less mechanical and more natural can reduce anxiety and improve patient comfort. In contexts where vulnerability is high, the gentle touch of a soft machine matters.

Exploring Extreme Environments

Soft robots are uniquely suited to environments that are difficult or dangerous for humans and rigid machines alike. In the deep sea, where pressure is immense and terrain is unpredictable, soft robots can withstand compression and adapt their shape to navigate tight spaces. Unlike rigid submersibles, they are less likely to suffer catastrophic failure when deformed.

In disaster zones, soft robots can squeeze through rubble to search for survivors, conforming to irregular spaces without causing further collapse. Their resilience to impacts and ability to absorb shocks make them well suited to chaotic conditions.

Even in space exploration, where one might assume rigidity is essential, softness has advantages. Inflatable habitats, flexible robotic arms, and deformable exploration devices can reduce mass and increase versatility. Soft robotics challenges assumptions about what machines must be made of to survive extreme conditions.

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability

Soft robotics also raises important questions about energy and sustainability. Traditional robots often rely on energy-intensive motors and rigid structures that must be strong enough to handle worst-case loads. Soft robots, by contrast, can exploit passive dynamics and elastic energy storage, reducing energy consumption.

For example, a soft robotic leg can store energy as it deforms during contact with the ground and release it during push-off, much like a tendon in an animal. This can improve efficiency and reduce the need for active control. In the long term, such principles could contribute to more sustainable robotic systems.

Materials choice also matters. Many soft robots are made from polymers derived from fossil fuels, raising concerns about environmental impact. However, research into biodegradable and bio-based materials is growing. Soft robotics, with its emphasis on material innovation, may ultimately contribute to greener technologies.

Intelligence Beyond the Brain

One of the most radical ideas emerging from soft robotics is that intelligence does not reside solely in a central processor. In biological systems, cognition is deeply embodied. The physical structure of an organism shapes how it perceives and interacts with the world.

Soft robots embody this principle. Their bodies filter sensory input, constrain possible actions, and respond dynamically to forces. This reduces the computational burden on control systems and allows for robust behavior in uncertain environments. Intelligence becomes a property of the entire system, not just the software.

This perspective resonates with broader trends in cognitive science and artificial intelligence, which increasingly recognize the importance of embodiment. Soft robotics provides a tangible demonstration that thinking machines may need soft bodies as much as fast processors.

Challenges and Open Questions

Despite its promise, soft robotics faces significant challenges. Modeling and predicting the behavior of soft systems remains difficult. Manufacturing soft robots with consistent, reliable properties is nontrivial, especially at scale. Integrating soft materials with electronics, power sources, and control systems requires innovative solutions.

Durability is another concern. Soft materials can degrade over time, especially when exposed to harsh conditions. Ensuring long-term reliability is essential for real-world applications. Researchers are actively exploring self-healing materials and hybrid designs that combine soft and rigid elements to balance flexibility and strength.

These challenges are not signs of failure but indicators of a young, evolving field. Just as early rigid robots faced limitations that were gradually overcome, soft robotics is advancing rapidly as materials science, computation, and design techniques improve.

Soft Robotics and the Future of Work

As robots become more integrated into human environments, their physical form will influence how they are perceived and accepted. Soft robots may play a key role in reshaping the future of work, particularly in roles that require close human interaction.

In collaborative manufacturing, soft robotic grippers can handle delicate components and work safely alongside people. In agriculture, soft robots can harvest fruits without damaging them. In caregiving, soft robotic assistants can provide physical support without the coldness associated with metal machines.

This does not mean rigid robots will disappear. Rather, the future is likely to involve hybrid systems that combine rigid structures for strength with soft components for interaction. The shift toward softness reflects a broader understanding that efficiency and power must be balanced with adaptability and care.

Cultural and Emotional Implications

The rise of soft robotics also challenges cultural narratives about machines. Hard, metallic robots often evoke fear or alienation, shaped by decades of dystopian fiction. Soft robots, with their pliable forms and gentle motion, suggest a different relationship between humans and technology.

This shift has emotional significance. Machines that feel less threatening may be more easily integrated into daily life. Softness can signal approachability, empathy, and safety, even if these qualities are ultimately the result of engineering rather than intention.

At a deeper level, soft robotics invites reflection on what it means to be mechanical or alive. When machines move like organisms and adapt like living systems, the boundary between the artificial and the natural becomes less distinct. This does not diminish the uniqueness of life but highlights the continuity between physical principles across domains.

The Philosophical Meaning of Squishiness

Soft robotics forces a reconsideration of long-held assumptions about control, precision, and perfection. Traditional engineering often values rigidity, predictability, and exactness. Soft robotics embraces uncertainty, variability, and imperfection as sources of strength.

This philosophical shift mirrors broader changes in science and society. Complex systems, from ecosystems to economies, are increasingly understood as dynamic and adaptive rather than static and controllable. Soft robots embody this worldview in material form.

There is something profoundly human in this approach. Living bodies are not perfect machines; they are resilient precisely because they are flexible and forgiving. By building robots that share these qualities, engineers are not making machines weaker but making them more capable of surviving in a complex world.

Conclusion: A Softer Technological Future

Soft robotics represents more than a new class of machines. It signals a transformation in how technology relates to the living world. By embracing softness, compliance, and adaptability, robots can move beyond controlled environments and become partners rather than tools.

The future of robotics will not be defined solely by faster processors or stronger materials, but by a deeper understanding of how bodies and environments interact. Soft robots show that intelligence can emerge from material properties, that safety can be built into form, and that power does not require rigidity.

In choosing squishiness over metal, soft robotics aligns technology more closely with life itself. It suggests a future where machines are not cold and distant but responsive and integrated, capable of touching the world without harming it. In that softness lies not fragility, but a new kind of strength—one that may define the next era of robotics and our relationship with the machines we create.