Beneath our feet, far below roads, fields, forests, and cities, lies one of the most important life-support systems on Earth. It does not glitter like rivers, roar like waterfalls, or stretch visibly like oceans. It is silent, hidden, and largely ignored—until it fails. Aquifers, vast underground stores of freshwater, sustain nearly half of the world’s drinking water and irrigate a large share of global agriculture. They make modern civilization possible in places where surface water is scarce or unreliable. Yet these invisible reserves are being drained at a pace that far exceeds their natural ability to recover.

The story of aquifers is a story of abundance mistaken for infinity, of slow processes colliding with fast human demand, and of a crisis unfolding quietly underground. To understand why aquifers matter so profoundly—and why their depletion poses one of the greatest environmental challenges of the twenty-first century—we must first understand what they are, how they work, and how deeply our lives depend on them.

What an Aquifer Really Is

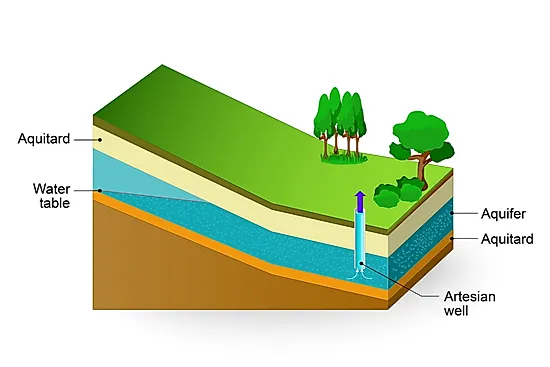

An aquifer is not an underground lake or a hidden river flowing through vast caverns, as popular imagination often suggests. Instead, an aquifer is a body of rock or sediment that can store and transmit water through tiny spaces between grains or through fractures in solid rock. Sand, gravel, sandstone, limestone, and fractured volcanic rock can all form aquifers, while dense materials like clay tend to block water movement.

Rain and melting snow seep slowly into the ground, pulled downward by gravity. As water percolates through soil and rock, it eventually reaches a depth where all available spaces are filled with water. This saturated zone is the domain of groundwater, and aquifers are the geological formations that hold and move it. Some aquifers lie just a few meters below the surface, while others extend hundreds or even thousands of meters underground.

What makes aquifers so valuable is their ability to release water steadily. When a well is drilled into an aquifer, water flows into the well either by natural pressure or by pumping. This reliability has made groundwater a cornerstone of human settlement, especially in regions where rivers dry up seasonally or rainfall is unpredictable.

The Slow Magic of Groundwater Recharge

Aquifers are renewed through a process known as recharge, which occurs when water from precipitation or surface sources infiltrates the ground and reaches the saturated zone. This process is slow—sometimes painfully slow by human standards. In shallow aquifers with permeable soils, recharge may occur over months or years. In deep aquifers sealed beneath layers of clay or rock, recharge can take centuries or millennia.

Some of the world’s most heavily used aquifers contain what is known as fossil water. This water entered the ground during ancient climatic periods when rainfall patterns were very different from today. In arid regions, fossil aquifers may receive little to no recharge under current climate conditions. When water is pumped from these aquifers, it is effectively a one-time withdrawal from a nonrenewable resource.

This mismatch between slow natural replenishment and rapid human extraction lies at the heart of the aquifer crisis. Groundwater behaves on geological timescales, while agriculture, industry, and cities demand water on daily, seasonal, and annual cycles. When pumping exceeds recharge, aquifers begin to shrink, often invisibly, until the consequences become impossible to ignore.

Why Aquifers Became the Backbone of Civilization

For most of human history, surface water shaped where people could live. Rivers supported agriculture, trade, and urban growth, while dry regions remained sparsely populated. The widespread use of groundwater changed this equation dramatically. With the invention of efficient drilling techniques and mechanical pumps, people gained access to water far from rivers and lakes.

Groundwater offered several advantages. It was naturally filtered by soil and rock, often making it cleaner than surface water. It was protected from evaporation, a critical benefit in hot climates. And it was available year-round, independent of seasonal rainfall. As a result, aquifers enabled the expansion of agriculture into drylands, supported booming cities, and fueled economic growth.

In many regions, groundwater use grew quietly, without the political and infrastructural complexity associated with large dams and reservoirs. Individual farmers drilled wells, industries secured private water supplies, and cities expanded their groundwater networks. Over time, this decentralized exploitation created a massive but largely unmonitored drawdown of underground water reserves.

Agriculture and the Thirst Below

No sector relies on aquifers more heavily than agriculture. Irrigation accounts for the majority of global groundwater extraction, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. Crops such as rice, wheat, maize, and cotton—staples of the global food system—depend on consistent water supplies that rainfall alone cannot provide in many climates.

Groundwater irrigation has been transformative. It has increased crop yields, stabilized food production, and lifted millions out of poverty. In regions like South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of the United States, aquifers underpin food security for hundreds of millions of people.

Yet this success has come at a cost. As farmers pump water to meet growing demand, water tables fall. Wells must be drilled deeper, increasing energy costs and excluding poorer farmers who cannot afford the investment. In extreme cases, aquifers become so depleted that wells run dry altogether, leaving communities without water for crops or daily life.

The tragedy is that groundwater depletion often accelerates silently. Fields remain green, harvests continue, and the illusion of abundance persists—until the tipping point is reached. By the time the damage is visible at the surface, recovery may take generations or may not be possible at all.

Urban Growth and Invisible Dependence

Cities, too, are deeply dependent on aquifers, even when rivers and reservoirs dominate the visible water supply. As urban populations grow, groundwater often serves as a critical backup during droughts or as a primary source when surface water is insufficient or polluted.

Many of the world’s largest cities draw heavily on aquifers beneath and around them. This extraction can lead to dramatic consequences. When groundwater is removed faster than it is replenished, the land above can sink—a process known as land subsidence. Buildings crack, roads warp, drainage systems fail, and flood risk increases, particularly in coastal cities.

Subsidence is not a sudden disaster but a slow deformation, unfolding over years or decades. Like aquifer depletion itself, it often escapes attention until the damage is extensive and costly to repair. In some cities, subsidence has permanently altered landscapes, increasing vulnerability to storms and sea-level rise.

The Physics and Chemistry of Aquifer Depletion

At a physical level, aquifer depletion occurs when water pressure within the pore spaces of rock decreases. In many aquifers, water pressure helps support the overlying material. When water is removed, grains can compact, reducing the aquifer’s ability to store water in the future. This compaction is often irreversible, meaning that even if recharge occurs later, the aquifer will never regain its original capacity.

Chemically, excessive pumping can degrade water quality. As water levels drop, saline water from deeper layers or nearby coastal areas can intrude into freshwater aquifers, rendering the water unsuitable for drinking or irrigation. In some regions, lowering the water table exposes minerals that release naturally occurring contaminants such as arsenic into the groundwater.

These processes illustrate a critical truth: aquifers are not just containers of water but complex systems. When disrupted, they respond in ways that can permanently alter both water quantity and quality.

Climate Change and the Fragile Balance

Climate change adds another layer of stress to already strained aquifers. Rising temperatures increase evaporation and plant water use, raising demand for irrigation. Changing precipitation patterns alter recharge rates, often reducing the amount of water that infiltrates the ground.

In many regions, climate change is intensifying droughts, pushing communities to rely even more heavily on groundwater during dry periods. This reliance can create a vicious cycle: drought drives increased pumping, which lowers water tables, reducing resilience to future droughts.

At the same time, extreme rainfall events—another consequence of climate change—do not necessarily translate into increased recharge. When rain falls too quickly, it runs off the surface rather than soaking into the ground, especially in urbanized or compacted landscapes. Thus, even a wetter climate does not guarantee healthier aquifers.

The Hidden Geography of Global Aquifers

Some aquifers span vast areas, crossing political boundaries and linking regions in unseen ways. These transboundary aquifers challenge traditional notions of water management, which are often based on surface waters and national borders.

The use of satellite data has revealed the scale of groundwater depletion in many major aquifers around the world. Measurements of Earth’s gravitational field show where groundwater mass is decreasing, exposing hotspots of unsustainable use. These findings confirm what local communities have experienced for years: the water beneath them is disappearing.

Yet governance of aquifers remains fragmented. In many places, groundwater is treated as a private resource tied to land ownership, encouraging overuse. Without coordinated management, individual users have little incentive to conserve water that others can freely extract.

Ecosystems That Depend on Groundwater

Aquifers do not serve humans alone. Many ecosystems depend on groundwater to survive, particularly in dry regions. Springs, wetlands, rivers, and oases often owe their existence to groundwater discharge. When aquifers are depleted, these ecosystems can collapse.

Groundwater-fed rivers may shrink or dry up, affecting fish populations and downstream water users. Wetlands can disappear, taking with them biodiversity and natural flood protection. Trees with deep roots that tap into groundwater reserves may die, altering entire landscapes.

These ecological losses are often irreversible on human timescales. They also highlight the interconnectedness of surface water and groundwater, reminding us that what happens underground ultimately reshapes the visible world.

The Illusion of Control

One of the most dangerous misconceptions about aquifers is the belief that technology alone can solve groundwater scarcity. Deeper wells, more powerful pumps, and advanced drilling techniques can delay the moment of reckoning, but they do not change the fundamental balance between recharge and extraction.

This illusion of control has allowed societies to postpone difficult decisions. As long as water continues to flow from taps and irrigation pipes, the crisis feels distant. Yet every additional meter of decline in water tables is a warning sign, a measure of how much future security is being traded for present convenience.

True solutions require not only technological innovation but also social, economic, and political change. They demand a shift from viewing groundwater as an infinite commodity to recognizing it as a shared, finite resource.

Managing Aquifers for the Long Term

Sustainable aquifer management begins with understanding. Measuring groundwater levels, mapping aquifer systems, and monitoring extraction are essential first steps. Without data, depletion remains invisible and unaddressed.

Equally important is aligning water use with natural limits. This may involve reducing water-intensive crops in arid regions, improving irrigation efficiency, and rethinking urban water consumption. In some cases, managed aquifer recharge—intentionally directing surface water into the ground—can help restore depleted aquifers, though it is not a universal solution.

Policy plays a decisive role. Effective groundwater governance requires clear rules, enforcement mechanisms, and cooperation among users. When communities are involved in managing their shared water resources, sustainable practices are more likely to emerge.

Cultural and Emotional Dimensions of Groundwater

Water is not just a physical resource; it is deeply woven into culture, identity, and emotion. For many communities, wells are symbols of security and continuity, passed down through generations. The drying of a well can feel like the loss of a living connection to the land.

Because aquifers are invisible, their decline often lacks the dramatic imagery that galvanizes public concern. A shrinking river can be photographed, a cracked reservoir can be broadcast on the news. A falling water table, by contrast, leaves no immediate visual trace. This invisibility makes it harder to inspire action, even as the stakes grow higher.

Storytelling, education, and science communication therefore play a crucial role. By making the hidden visible—through data, narratives, and shared experience—we can foster a deeper emotional connection to groundwater and a stronger commitment to its protection.

The Future Beneath Our Feet

The fate of aquifers is inseparable from the future of human civilization. As populations grow and climates change, pressure on groundwater will only increase. The choices made today will determine whether aquifers remain a source of resilience or become a symbol of irreversible loss.

There is still time to change course. Aquifers respond slowly, but they do respond. With careful management, reduced demand, and respect for natural limits, groundwater systems can stabilize and, in some cases, recover. The challenge lies not in a lack of knowledge, but in the will to act before the damage becomes final.

Conclusion: Learning to See the Invisible

Aquifers teach us a profound lesson about the nature of sustainability. They remind us that the most essential systems may be the least visible, and that abundance can mask fragility. By drawing water from the depths without regard for replenishment, humanity has treated aquifers as if they were endless. Science tells a different story—one of slow renewal, delicate balance, and finite capacity.

To protect aquifers is to practice patience, foresight, and humility. It is to accept that some of the most important work happens out of sight, over timescales longer than a human lifetime. In learning to value the invisible water beneath our feet, we take a step toward a more sustainable relationship with the planet that sustains us.