What does it mean to be aware? To feel the warmth of the sun, to savor the sweetness of honey, or to grieve at the loss of a loved one? These experiences are not simply patterns of electrical signals coursing through neurons—they are lived realities, filled with texture and meaning. This inner dimension of life, this “what it is like” to be, is consciousness. And though we navigate the world each day immersed in its presence, science still stands at the threshold of its greatest puzzle: how and why subjective experience arises from physical matter.

The challenge is known as the hard problem of consciousness, a term coined by philosopher David Chalmers in the 1990s. While neuroscience can explain many “easy problems” of cognition—how the brain perceives shapes, remembers facts, or controls movement—the hard problem asks something deeper. Why does processing information feel like anything at all? Why isn’t the brain just a silent computer, performing calculations without awareness? Why is there an inner light behind the eyes?

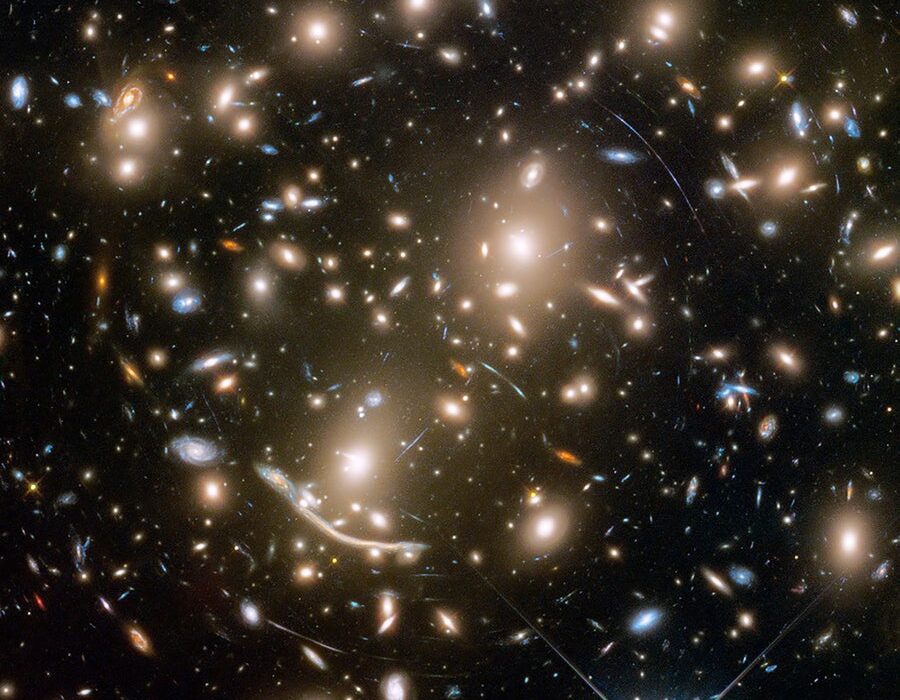

The enigma of consciousness is not merely academic. It touches the essence of who we are. Without consciousness, the universe would be a cold expanse of particles and forces. With it, stars are beautiful, love is real, and life has meaning. To grapple with consciousness is to grapple with existence itself.

The Easy Problems and the Hard Problem

Modern neuroscience has made dazzling progress. We can map brain regions, record electrical activity, and even decode visual images from neural signals. Scientists understand how sensory information travels from receptors in the eye or ear to the cortex, how neurons fire in synchrony, and how networks coordinate to produce behavior. These are the so-called “easy problems” of consciousness—not easy in practice, but tractable within the framework of physical science.

Yet all this leaves the hard problem untouched. Imagine a robot programmed to detect red light and respond by saying “I see red.” We could design circuits, measure responses, and replicate the behavior perfectly. But nothing in the circuitry explains what it feels like to see red. That raw sensation—the redness of red—is what philosophers call qualia. The hard problem asks: why should any physical process give rise to qualia at all? Why doesn’t the brain operate like a robot, processing without feeling?

This gap between mechanism and experience is a chasm that empirical research struggles to cross. For centuries, thinkers have wrestled with it, from Descartes declaring mind and body separate substances, to modern materialists insisting the mind must be reducible to the brain. But the mystery endures, stubbornly resisting reduction.

The Brain as a Biological Machine

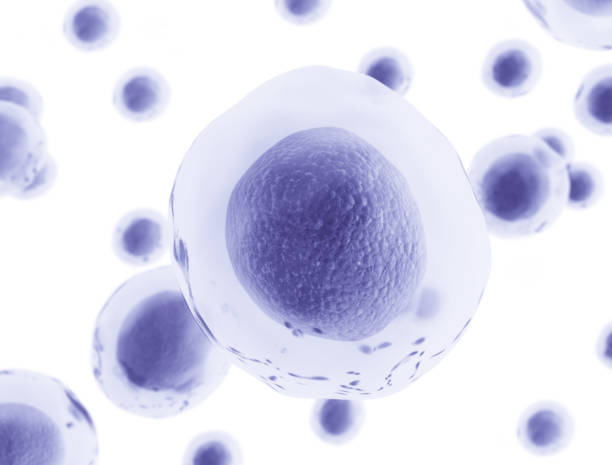

One approach is to assume consciousness is an emergent property of the brain’s complexity. Just as liquidity emerges when countless molecules of water interact, perhaps awareness emerges when billions of neurons form intricate networks. The brain, with its eighty-six billion neurons and trillions of synapses, is the most complex structure known in the universe. Could consciousness be the natural outcome of such complexity?

Neuroscientists point to phenomena like global neuronal workspace theory, which suggests consciousness arises when information is globally broadcast across widespread brain networks. Another theory, integrated information theory (IIT), argues that consciousness corresponds to the degree of information integration in a system—the higher the integration, the richer the experience. According to IIT, consciousness may be measured as “phi,” a mathematical quantity.

These theories attempt to map patterns of brain activity to subjective states, and they have experimental support. Certain neural signatures, such as synchronized oscillations between cortical regions, correlate with conscious perception. Patients under anesthesia, for example, show a breakdown of these signatures, suggesting that consciousness dims when integration fails.

And yet, even the most sophisticated models describe correlates of consciousness, not its essence. They explain how information is shared, but not why sharing feels like something. The hard problem persists: how do electrical impulses in gray matter conjure the shimmering world of subjective awareness?

Philosophical Quandaries

Philosophy refuses to let science rest easy with its correlations. Chalmers argued that even if we mapped every neuron and decoded every signal, we would still face the “explanatory gap.” Knowing the mechanics does not reveal why the mechanics are accompanied by experience.

One famous thought experiment is the story of Mary, the color scientist. Mary lives in a black-and-white room but knows everything about the physics of light and the biology of color vision. One day, she steps outside and sees red for the first time. Has she learned something new? Intuitively, yes—she now knows what red feels like. This suggests that subjective experience contains knowledge irreducible to physical facts.

Another puzzle is the possibility of philosophical zombies—beings that behave exactly like humans, with identical brains and behaviors, but without any inner experience. If such zombies are conceivable, then consciousness cannot be fully explained by physical processes alone. These thought experiments expose the stubbornness of the hard problem.

Beyond the Brain: Radical Theories

Frustration with the hard problem has inspired some thinkers to explore more radical ideas. One such idea is panpsychism—the notion that consciousness is a fundamental feature of reality, present in all matter to some degree. Just as mass and charge are basic properties, perhaps consciousness pervades the universe, with complex systems like brains merely amplifying it. This view, once considered fringe, has gained serious philosophical attention.

Another radical approach comes from quantum mechanics. Some physicists, such as Roger Penrose, suggest that quantum processes in microtubules inside neurons could give rise to consciousness. According to this controversial theory, consciousness is tied to the fundamental indeterminacy of quantum states, giving it a role in shaping reality itself. While evidence for this remains limited, the hypothesis reflects the desperation to link mind and matter at their most fundamental levels.

Others propose that consciousness may not be “produced” by the brain at all, but rather that the brain acts as a filter or receiver of consciousness, much like a radio tuning into signals. This idea harks back to William James and other early psychologists, and while speculative, it highlights our limited assumptions about what consciousness must be.

The Limits of Science

Science thrives on objectivity, but consciousness is intrinsically subjective. Every measurement of brain activity is third-person observation, while consciousness itself is first-person experience. Bridging these perspectives may be the greatest challenge of all. How can we build a science of the subjective?

Some researchers argue for new methodologies that incorporate subjective reports into empirical frameworks. Others suggest that consciousness might demand entirely new paradigms of science, just as relativity and quantum mechanics once forced revolutions in physics. Perhaps the tools we currently wield are too blunt to cut through the mystery.

And yet, to dismiss the problem as unsolvable is to surrender the very heart of human inquiry. For what question is more urgent than: why are we aware at all? Without consciousness, there is no science, no art, no love, no suffering. Consciousness is the stage upon which the entire play of life unfolds.

Consciousness and Artificial Intelligence

The rise of artificial intelligence has brought fresh urgency to the hard problem. As machines grow more sophisticated, simulating human conversation, vision, and reasoning, the question looms: could AI ever be conscious?

If consciousness is merely computation, then in principle a machine with sufficient complexity could awaken. But if consciousness requires something beyond information processing—some intrinsic quality of biological matter or a fundamental property of the universe—then machines may forever remain dark inside, however clever their behavior.

This is not a question of idle speculation. If AI were conscious, ethical implications would follow. Could a machine suffer? Could it have rights? To answer such questions, we must first answer what consciousness truly is. The hard problem, once a philosophical curiosity, may soon have profound consequences for society.

The Human Dimension

Beyond theories and experiments, the mystery of consciousness is deeply personal. Each of us carries within an inner universe, vast and ineffable. Our joys, fears, and dreams are all woven from the fabric of awareness. Science may dissect the brain, but only we ourselves can feel the warmth of love or the sting of sorrow.

This subjective richness is what makes life meaningful. Imagine a world without consciousness: no beauty in sunsets, no melody in music, no tenderness in touch. The cosmos might roll on indifferently, but without awareness, it would all be mute and empty. Consciousness is not an ornament of existence; it is its very essence.

Perhaps this is why the hard problem stirs such fascination and frustration. We are trying to solve the riddle of ourselves. In probing consciousness, science peers into the mirror of being, seeking not only knowledge but understanding.

Toward the Horizon

Where, then, does the quest stand? Neuroscience will continue to uncover the brain’s mechanisms, providing ever-finer maps of the correlates of consciousness. Philosophy will continue to sharpen arguments, testing the boundaries of thought. Radical theories may rise and fall, and perhaps one day, a breakthrough will come—an insight as radical as relativity or quantum mechanics, one that dissolves the hard problem into clarity.

Or perhaps consciousness will forever elude full explanation, remaining an irreducible mystery. But even if it does, the pursuit is not in vain. To chase the mystery is to expand the human spirit, to deepen our wonder at the miracle of being.

Albert Einstein once remarked that the most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. Consciousness, the inner light that makes mystery possible, may be the greatest wonder of all. Whether we solve it or not, its presence is the reason we care to solve anything at all.

Conclusion: The Fire Within

Consciousness is both ordinary and extraordinary. It is in every breath, every thought, every moment we live. And yet it is the most perplexing phenomenon science has ever faced. The hard problem challenges us to explain not just the machinery of life but the fire that animates it—the difference between a world observed and a world experienced.

In seeking answers, we confront the deepest truths about ourselves. We are not merely bodies of matter and energy; we are beings who feel, who know, who wonder. And that wonder may itself be the bridge that carries us, however imperfectly, across the gulf of the hard problem.

Until then, consciousness remains both our greatest gift and our greatest riddle—a light burning within the darkness, asking, always asking, why it shines at all.