Imagine standing on a quiet hill a thousand years from now. The wind moves through forests that once were cities. Rivers run freely where highways once roared. The sky is clearer than any human in the 21st century ever knew it. No voices, no engines, no lights at night—only the deep, patient rhythms of a planet continuing its ancient work.

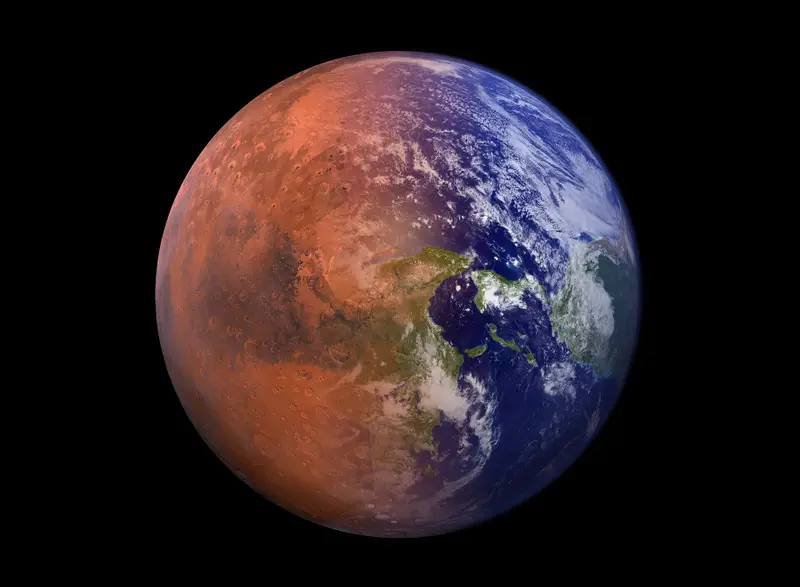

The question of what Earth will look like after humans is not just a speculative exercise. It is a mirror held up to our present moment. It forces us to confront how powerful our species has been, how fragile our systems are, and how resilient the planet truly is. Scientifically, we know a great deal about how ecosystems recover, how materials decay, and how climate systems respond over centuries. Emotionally, this vision stirs something deeper: humility.

One thousand years is a blink in geological time, yet it is long enough for the fingerprints of human civilization to fade and for Earth to reclaim much of what was altered. The planet will not forget us entirely, but it will move on.

The Silence After Us

The first and most striking change after humans vanish is silence. Not an absolute silence, but the absence of mechanical noise that has defined the modern era. Within days, power plants shut down as fuel systems fail. Electrical grids collapse. Artificial light disappears from the night sky, allowing darkness to return in its natural form.

Within years, cities grow quiet. Buildings stand intact at first, frozen monuments to human ambition. But without maintenance, decay begins immediately. Water infiltrates cracks. Metal corrodes. Roots push into foundations. Nature does not rush, but it never stops.

Animals that once avoided human-dominated landscapes begin to explore them. Urban environments, already home to adaptable species, become gateways for ecological return. Birds nest in skyscrapers. Mammals roam streets that once choked with traffic. The absence of humans removes fear as a controlling force, and life responds quickly.

Cities Become Ruins, Then Habitats

Over centuries, cities undergo a predictable transformation guided by physics, chemistry, and biology. Concrete crumbles as steel reinforcements rust and expand. Glass shatters under thermal stress and storms. Asphalt breaks apart as plants exploit microscopic weaknesses.

In humid regions, forests reclaim urban cores surprisingly fast. Trees sprout from rooftops. Moss and fungi accelerate the breakdown of stone and brick. In drier climates, wind and temperature fluctuations do the work more slowly, but the result is the same: human structures lose their dominance.

After a thousand years, recognizable city outlines still exist in places, but only as ghostly frameworks. Large stone monuments may remain partially intact, while wooden structures have long since returned to soil. Subway tunnels collapse or flood, becoming subterranean rivers or sealed chambers preserved in darkness.

These ruins are not barren. They become complex ecosystems. Cavities provide shelter. Artificial cliffs host nesting birds. Materials once engineered for permanence now serve life in unexpected ways.

The Fate of Roads, Bridges, and Infrastructure

Human infrastructure is vast, but it is not immortal. Roads crack quickly without repair. Freeze-thaw cycles pry them apart. Plant roots accelerate the process. Within centuries, most paved roads are unrecognizable, reduced to gravel mixed with soil.

Bridges fare differently depending on their construction. Steel bridges corrode, eventually collapsing into rivers. Stone arches may last longer, echoing the durability of ancient structures, but even they succumb to erosion and plant growth over time.

Dams represent one of the most significant post-human changes. Without maintenance, many fail within decades to centuries. When they do, rivers reclaim their ancient courses. Sediments trapped for generations surge downstream, reshaping landscapes. Floodplains revive. Fish migrations resume. These moments are violent but restorative, releasing ecosystems that had been artificially constrained.

Pipelines rupture. Mines flood. Quarries soften into wetlands or lakes. Earth reclaims not only the surface but also the scars carved deep into its crust.

Oceans After Humans

The oceans carry some of humanity’s longest-lasting legacies. Plastics, chemical pollutants, and altered ecosystems do not vanish quickly. Yet even here, Earth responds with relentless persistence.

In the absence of new pollution, existing plastics slowly fragment under sunlight and mechanical stress. Microplastics persist for centuries, circulating through marine food webs, but over time they become buried in sediments or broken down further by chemical processes. They do not disappear completely in a thousand years, but their biological impact gradually diminishes as concentrations decline.

Coral reefs, devastated by warming and acidification, face a complicated future. If human-driven climate pressures cease, ocean chemistry slowly stabilizes. Some coral species adapt and recolonize. Others are lost forever. Reef structures rebuild over centuries, not to their former exact forms, but into new configurations shaped by altered conditions.

Whales, fish, and marine mammals rebound dramatically without hunting, shipping noise, and fishing pressure. Ocean ecosystems become richer and more complex, though forever marked by the memory of industrial exploitation.

Climate in a Humanless Millennium

One of the most misunderstood aspects of a post-human Earth is climate. The planet does not instantly reset. Carbon dioxide released by human activity remains in the atmosphere for centuries. Temperatures decline slowly, not abruptly.

In the first few centuries, global temperatures remain elevated compared to pre-industrial levels. Ice sheets respond sluggishly, continuing to melt or stabilize depending on the extent of prior warming. Sea levels remain high, reshaping coastlines permanently. Some low-lying regions never re-emerge.

By the end of a thousand years, Earth’s climate begins to settle into a new equilibrium. It is not the same as before humans. Forests grow in regions once too cold. Deserts expand or contract depending on shifting atmospheric circulation. The planet adapts, not by restoring a previous state, but by creating a new one.

Earth has experienced far more extreme climate shifts in its deep past. From that perspective, the human era is a brief but intense disturbance, one the planet absorbs and moves beyond.

Nuclear Shadows and Long-Lived Traces

Among the most enduring human artifacts are nuclear materials. Reactors shut down without human intervention, many suffering meltdowns in the early decades. Radiation spreads locally but does not sterilize the planet. Nature adapts even here. Life persists in radioactive environments, exploiting niches humans once thought uninhabitable.

Nuclear waste storage sites remain dangerous for thousands of years, but even these are not eternal. Containers corrode. Warning symbols fade. Eventually, geological processes bury and isolate much of this material. Radiation levels decline through decay, following immutable physical laws.

In a thousand years, radiation hotspots remain detectable, but they are localized anomalies rather than global threats. They stand as one of the clearest signatures of technological civilization, silent markers of a species that mastered the atom but not itself.

Agriculture Returns to Wilderness

Fields once meticulously managed begin their quiet transformation almost immediately. Without plowing, planting, and harvesting, soil systems rebuild. Microbial communities recover. Native plants outcompete domesticated crops, which lack resilience without human care.

Within decades, grasslands replace farms. Within centuries, forests return in suitable climates. This process, known as ecological succession, follows patterns observed whenever land is abandoned. The speed varies, but the outcome is consistent: complexity increases.

Former agricultural landscapes often become biodiversity hotspots, enriched by deep soils and altered hydrology. Even invasive species eventually integrate into new ecological balances, though some losses of native species are permanent.

The idea that humans “feed the world” dissolves in this future. Earth feeds itself, as it did for hundreds of millions of years before agriculture.

The Return of Wildness

Perhaps the most emotionally powerful change after humans is the return of wildness. Not a romantic fantasy of untouched Eden, but a dynamic, sometimes harsh, always alive world.

Large predators reclaim territories. Ecosystems regain top-down balance. Forests grow dense, then burn, then regrow. Rivers shift. Coastlines erode and rebuild. Life is not gentle, but it is whole.

Extinctions caused by humans cannot be undone. Species lost are gone forever. Yet evolution continues. New species emerge. Genetic diversity increases as populations expand and adapt without human pressure.

The biosphere does not mourn humans. It responds to absence with abundance.

The Night Sky After Artificial Light

One of the most immediate gifts of a humanless Earth is darkness. Light pollution disappears within days. The Milky Way becomes visible from every point on the planet.

Nocturnal ecosystems, long disrupted by artificial lighting, return to natural cycles. Migratory birds navigate accurately. Insects follow ancient rhythms. Even plants respond to restored patterns of night and day.

This darkness is not emptiness. It is fullness restored, a reminder that Earth evolved under stars, not streetlights.

Geological Time and Human Time

From a geological perspective, a thousand years is almost nothing. Mountain ranges rise and erode over millions of years. Continents drift over tens of millions. Yet the human impact is sharp enough to be recorded in stone.

Future geologists, human or otherwise, would find a thin layer rich in plastics, unusual metals, and altered isotopes. This layer marks the Anthropocene, a brief but intense chapter in Earth’s story.

What is remarkable is not that humans altered the planet, but how quickly. No previous species changed atmospheric chemistry at this scale in such a short time. That fact is both a testament to human ingenuity and a warning encoded in stone.

The Emotional Meaning of a World Without Us

Imagining Earth after humans can feel unsettling, even sad. It touches on fears of extinction and insignificance. But it can also be strangely comforting.

It reminds us that Earth does not depend on us to exist. It never did. The planet is not fragile in the way we are. It is resilient beyond imagination. This does not excuse destruction; rather, it reframes responsibility. We are not guardians of a helpless world, but participants in a vast system that will continue with or without us.

This perspective can deepen care rather than diminish it. Knowing Earth will survive does not mean our actions do not matter. They matter profoundly to us, to other species, and to the quality of life in the time we do exist.

Lessons Written in the Future

A thousand years from now, Earth will be quieter, wilder, and more balanced in many ways. It will still bear scars, but they will be woven into new patterns of life. The planet will not look ruined. It will look changed, as it always has.

The true lesson of imagining this future is not about disappearance, but about presence. It asks what kind of trace we want to leave, knowing it will fade. It challenges the illusion of permanence that drives so much human behavior.

Physics, biology, and geology all tell the same story: nothing lasts forever, but everything matters while it exists.

Earth Continues

In the end, Earth in 1,000 years without humans is not an apocalypse. It is a continuation. Rivers flow. Forests breathe. Oceans pulse. The planet does what it has always done: it lives.

The absence of humans is not a judgment, nor a triumph. It is simply another state in an ongoing story billions of years long. The Earth has known fire and ice, mass extinctions and explosions of life. Humanity is one chapter, intense and transformative, but not the final one.

And perhaps the most profound realization is this: imagining Earth after humans is really about understanding Earth with humans. It is about recognizing that we are temporary, powerful, and deeply connected to a world that does not belong to us, but of which we are undeniably a part.