Eighty million years ago, the Late Cretaceous world looked vastly different than the one we inhabit today. While North America and Asia were massive landmasses teeming with life, Europe was a scattered island archipelago. For decades, a mystery haunted the halls of paleontology: why were the ceratopsians—those iconic horned, beaked herbivores—seemingly missing from the European landscape? They were abundant in the fossil records of the surrounding continents, which were linked by land bridges and island chains, yet the European record remained stubbornly quiet. A few bone fragments had surfaced over the years, but they were often dismissed or disputed, leaving scientists to wonder if these creatures had simply bypassed the region entirely.

A Case of Mistaken Identity

The silence, it turns out, was not due to an absence of dinosaurs, but a case of hidden identity. For years, fossils belonging to these horned pioneers had been tucked away in museum drawers or sitting on display shelves, masquerading as entirely different species. The breakthrough came when a team of researchers decided to take a second look at a specific specimen found in Hungary, known as Ajkaceratops. For a long time, the status of this dinosaur was a subject of heated debate. The original find was nothing more than a single, partial snout, which provided very little for scientists to work with. Because of its shape, many paleontologists argued that it wasn’t a ceratopsian at all, but rather a relative of the iguanodontians, a group of herbivores that shared a similar skull structure.

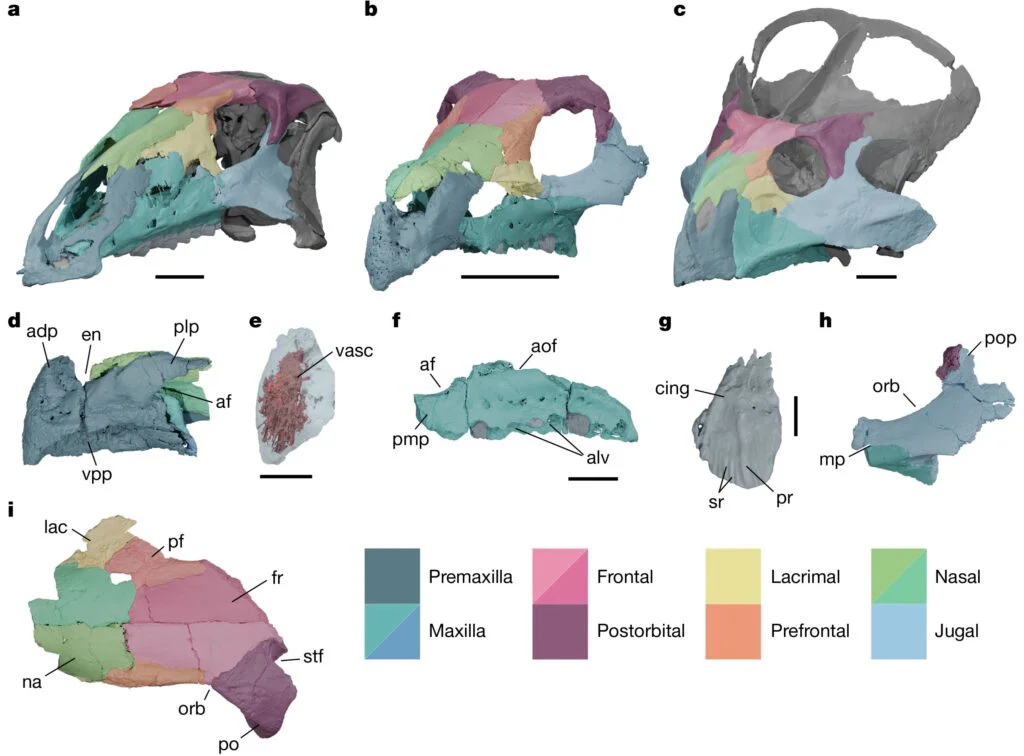

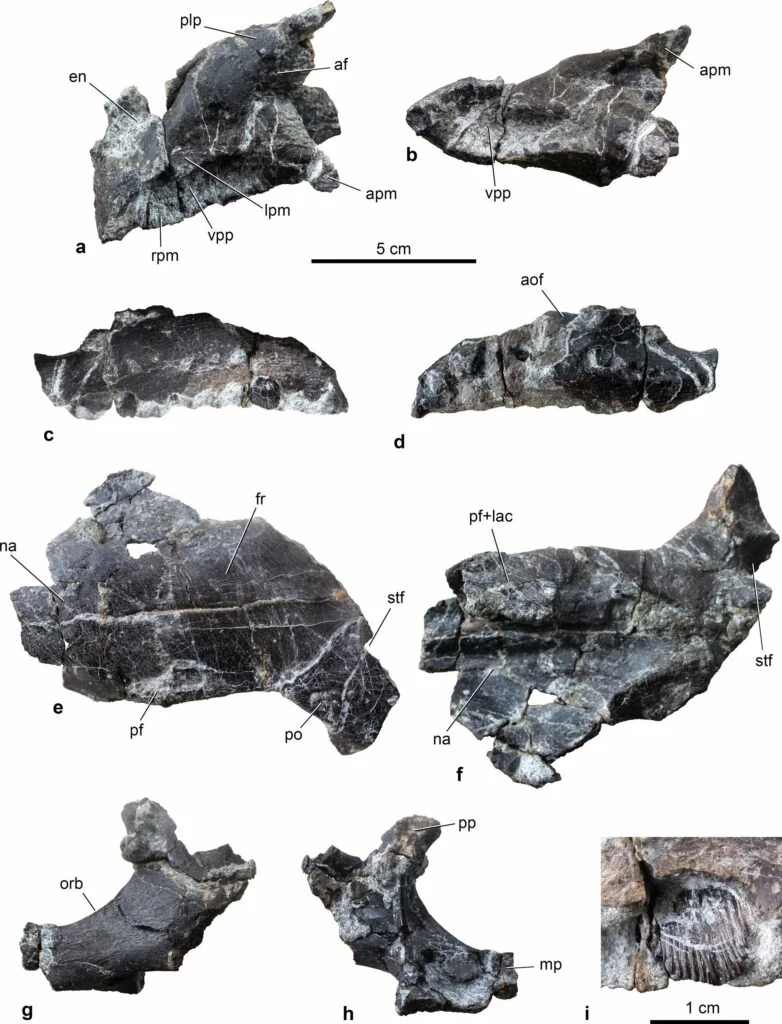

To solve the puzzle, the research team turned to modern technology, employing CT scanning and 3D modeling to peer inside the skull of a more complete specimen. By digitally reconstructing the internal anatomy, they were able to compare it to known relatives from Asia. The results were undeniable. The dinosaur possessed a sharp, hook-like beak and a deeply vaulted roof of the mouth, a specific anatomical signature found in primitive horned dinosaurs but completely absent in iguanodontians. This digital autopsy proved that the horned dinosaurs had indeed made Europe their home, living right under the noses of researchers who had mistaken them for their cousins.

Unmasking the Ghosts of the Archipelago

Once the true nature of Ajkaceratops was revealed, the scientific “dominoes” began to fall. The researchers realized that if one dinosaur had been misidentified, others likely were too. They turned their attention to a mysterious specimen from Romania that had been a taxonomic nomad for years, categorized and re-categorized as various different species as experts struggled to place it on the family tree. Armed with their new understanding of European ceratopsian anatomy, the team recognized the Romanian fossil for what it truly was. They officially moved it into the ceratopsian group and gave it a new name: Ferenceratops.

This realization acted as a skeleton key, unlocking a new perspective on the Late Cretaceous period. These dinosaurs hadn’t vanished; they had been hiding in plain sight, obscured by the limitations of earlier anatomical comparisons and the poor preservation of their remains. The discovery suggests that the island archipelago of Europe was far more diverse than previously imagined, serving as a vital habitat for groups of dinosaurs that were once thought to be restricted to the larger eastern and western continents.

Reconstructing a Lost World

The implications of this study reach far beyond the identification of two specific dinosaurs. It challenges the conventional understanding of how herbivorous dinosaurs evolved and spread across the globe. For a long time, the European fossil records were seen as an outlier, a place where certain famous lineages simply didn’t thrive. This new evidence indicates that our maps of ancient migrations are incomplete. The researchers are now calling for a massive overhaul of European fossil collections, urging their colleagues to revisit existing specimens with fresh eyes and advanced technology.

There is a sense of urgency in their message, as they believe many more ancient relics recovered from countries across the continent may have been mislabeled for decades. By re-evaluating these herbivorous dinosaur assemblages, scientists can begin to piece together a more accurate story of life on the European islands. It is a reminder that the history of our planet is not just written in the stones we find, but in how we choose to interpret them.

Why This Discovery Changes Everything

This research matters because it forces a fundamental re-evaluation of dinosaur history. It proves that even in a field as old as paleontology, “new” discoveries don’t always require digging in the dirt; sometimes, they require looking at what we already have through a different lens. By confirming the presence of ceratopsians in Europe, scientists have bridged a massive gap in the ornithischian dinosaur evolution timeline.

Understanding how these creatures moved between Asia, North America, and the European islands helps us understand how species adapt to fragmented environments. It shifts our view of the Late Cretaceous from a series of isolated ecosystems into a more connected and dynamic world. As paleontologists begin to unmask more “hidden” dinosaurs in collections across Europe, the story of the horned giants will only grow more complex and fascinating, proving that the past still has plenty of secrets left to tell.

Study Details

Susannah C. R. Maidment et al, A hidden diversity of ceratopsian dinosaurs in Late Cretaceous Europe, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09897-w