Deep inside every living cell, tiny engines hum away, turning the food we eat into the energy that keeps us alive. Most of the time, we never notice this microscopic labor. But a new line of research suggests that by nudging these engines to work just a little harder, scientists may have found a promising new way to help the body burn more calories. The work does not rely on forcing the body into extremes. Instead, it explores a subtle shift in how energy is handled at the most fundamental level of life.

Researchers have developed experimental drugs that encourage mitochondria, the energy-producing structures inside cells, to burn fuel less efficiently. The result is simple in principle but powerful in effect: more calories are consumed, and more energy is released as heat. These findings, recently published in Chemical Science and highlighted as “pick of the week,” could open the door to new treatments for obesity and improvements in metabolic health.

The study was led by Associate Professor Tristan Rawling from the University of Technology Sydney, in collaboration with scientists from Memorial University of Newfoundland in Canada. Together, they revisited an old and dangerous idea and reshaped it into something potentially safer and far more precise.

The Weight of a Global Problem

Obesity is not a niche concern or a localized issue. It is a global epidemic and a major risk factor for a wide range of diseases, including diabetes and cancer. Existing treatments can help, but many current obesity drugs require injections and may cause unpleasant or serious side effects. For people and healthcare systems alike, this creates a pressing need for alternatives that are both effective and safe.

Against this backdrop, the idea of boosting the body’s own energy-burning processes is especially appealing. Instead of suppressing appetite or interfering with hormones, this approach works by changing how cells use fuel. It asks a simple question: what if cells could be encouraged to waste a little energy, in a controlled way, without harming themselves?

The answer lies in a class of molecules known as mitochondrial uncouplers.

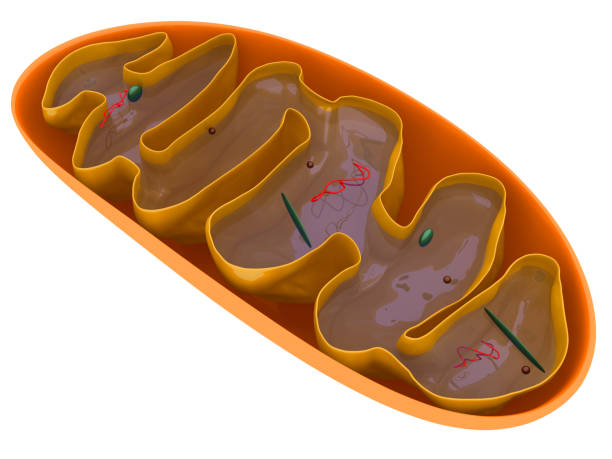

When the Powerhouse Leaks Energy

To understand mitochondrial uncouplers, it helps to understand what mitochondria normally do. As Associate Professor Rawling explains, “Mitochondria are often called the powerhouses of the cell. They turn the food you eat into chemical energy, called ATP or adenosine triphosphate. Mitochondrial uncouplers disrupt this process, triggering cells to consume more fats to meet their energy needs.”

Under normal conditions, mitochondria convert nutrients into ATP with impressive efficiency. This efficiency is essential for life, but it also means that excess energy is easily stored, often as fat. Uncouplers interfere with this efficiency. They make mitochondria less tidy and more wasteful, so that some of the energy from food is lost as heat rather than stored or used.

Associate Professor Rawling offers a vivid analogy. “It’s been described as a bit like a hydroelectric dam. Normally, water from the dam flows through turbines to generate electricity. Uncouplers act like a leak in the dam, letting some of that energy bypass the turbines, so it is lost as heat, rather than producing useful power.”

In the context of the human body, that “leak” forces cells to burn more fuel just to keep up with their energy demands.

A Dark Chapter from the Past

This idea is not entirely new. In fact, mitochondrial uncoupling has a long and troubling history. Compounds that trigger this process were first discovered around a century ago, and the results were dramatic and often deadly.

“During World War I, munitions workers in France lost weight, had high temperatures and some died. Scientists discovered this was caused by a chemical used at the factory, called 2,4-Dinitrophenol or DNP,” said Associate Professor Rawling.

DNP worked exactly as intended, at least from a metabolic perspective. It disrupted mitochondrial energy production and drove metabolism into overdrive. People burned calories rapidly and lost weight. The effect was so striking that DNP was briefly marketed in the 1930s as one of the first weight-loss drugs.

But the danger soon became clear. “DNP disrupts mitochondrial energy production and increases metabolism. It was briefly marketed in the 1930s as one of the first weight-loss drugs. It was remarkably effective but was eventually banned due to its severe toxic effects. The dose required for weight loss and the lethal dose are dangerously close,” he said.

The problem was not the idea of uncoupling itself, but the lack of control. Too much uncoupling caused cells to overheat and fail, leading to severe toxicity and death. For decades, this history cast a long shadow over the field.

Tuning the Fire, Not Igniting an Inferno

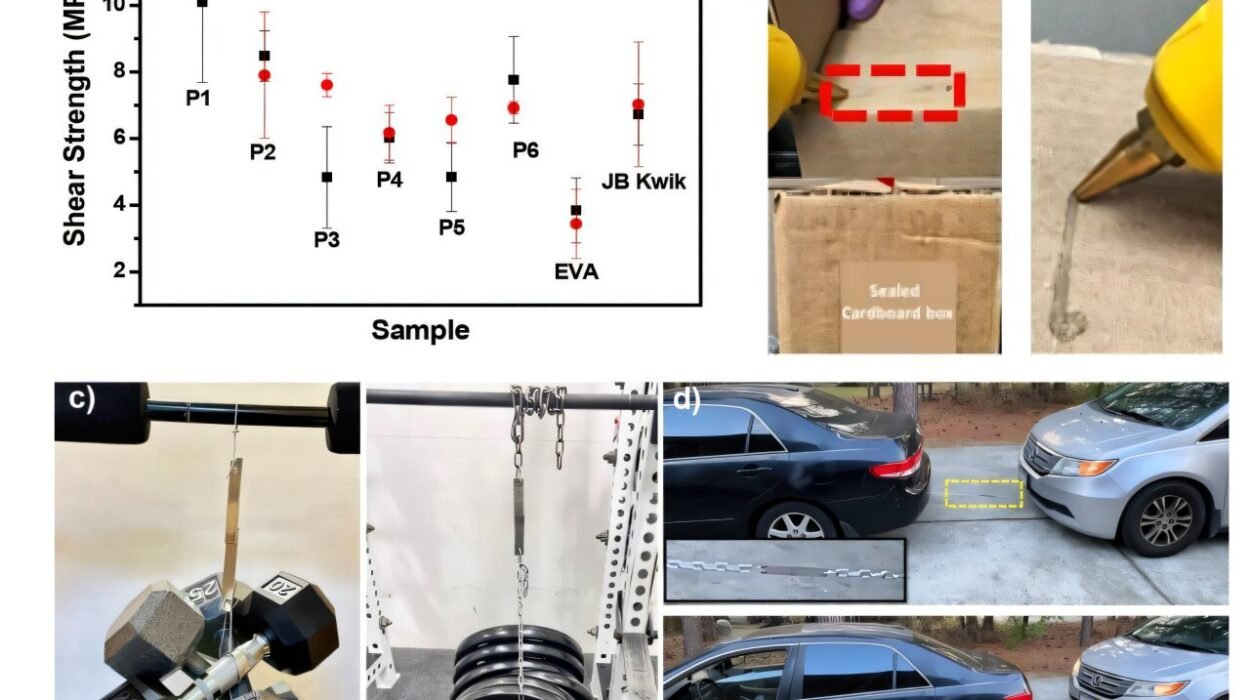

The new study takes a fundamentally different approach. Instead of using powerful uncouplers that overwhelm cells, the researchers set out to design “mild” mitochondrial uncouplers. These are molecules whose effects can be carefully adjusted by changing their chemical structure.

By fine-tuning these structures, the team was able to control how strongly the experimental drugs increased cellular energy use. Some of the molecules gently encouraged mitochondria to work harder without damaging cells or interfering with their ability to produce ATP. Others, however, crossed the line and recreated the dangerous uncoupling seen with older, toxic compounds.

This contrast turned out to be crucial. It allowed the researchers to identify what makes a mitochondrial uncoupler safe or unsafe. The mild uncouplers slowed the energy process just enough for cells to handle the change. Instead of triggering a runaway reaction, they introduced a manageable inefficiency.

In essence, the researchers learned how to adjust the size of the “leak in the dam,” making it small enough to be beneficial rather than catastrophic.

Beyond Weight Loss

The potential benefits of mild mitochondrial uncouplers may extend beyond burning calories. Another key finding of the study is that these gentler compounds reduce oxidative stress inside cells. Oxidative stress is a form of cellular strain that can damage structures and impair function.

By lowering this stress, mild uncouplers could improve overall metabolic health. The researchers suggest that this effect might also contribute to anti-aging benefits and protection against neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia. These possibilities remain speculative at this stage, but they highlight the broad biological impact of mitochondrial function.

What makes this particularly intriguing is that all of these effects arise from a single, carefully controlled change in how cells handle energy.

Why This Research Matters

This work is still at an early stage, and no new drug is ready for clinical use. Yet its importance lies in the framework it provides. By showing that mitochondrial uncoupling can be made mild, tunable, and potentially safe, the researchers have reopened a field that was once considered too dangerous to explore.

Obesity remains a major public health challenge, and current treatments do not work for everyone. A new class of drugs that helps the body burn more energy, without injections or severe side effects, could transform how metabolic disease is treated. Beyond weight loss, the possibility of improving metabolic health, reducing cellular stress, and protecting against age-related diseases adds further significance.

At its core, this research demonstrates the power of precision in biology. By understanding and respecting the delicate balance inside our cells, scientists are learning how to harness processes that were once lethal and turn them into tools for health. The tiny engines inside us have always been burning fuel. Now, we may finally be learning how to guide that fire safely.

More information: Ethan Pacchini et al, The role of transmembrane proton transport rates in mild mitochondrial uncoupling by arylamide substituted fatty acids, Chemical Science (2026). DOI: 10.1039/d5sc06530e