For years, a particular mathematical statement sat quietly at the foundation of quantum information theory, rarely questioned and widely relied upon. Known as the generalized quantum Stein’s lemma, it offered researchers a way to understand how well quantum states can be told apart when many identical copies are available. That question is not abstract bookkeeping. It lies at the heart of how quantum technologies store, process, and transform information under strict physical rules.

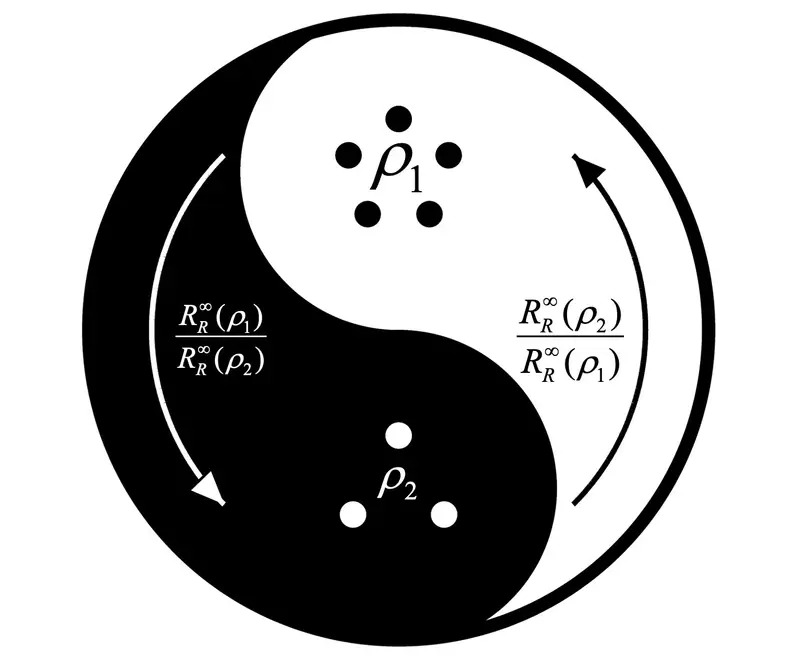

Quantum information theory itself emerged to make sense of these rules. As quantum devices grew more sophisticated, researchers developed frameworks to describe what transformations are possible when only limited operations are allowed. Among the most influential of these frameworks are resource theories, which treat certain quantum states as valuable resources and others as free. The generalized quantum Stein’s lemma, introduced in 2008 by two scientists at Imperial College London, played a crucial role in this landscape. It connected the ability to distinguish quantum states with deeper ideas about resource conversion.

For more than a decade, the lemma was used as if its foundations were firm. Papers were written. Results were extended. Entire arguments leaned on its conclusions. Then, quietly at first, something began to crack.

When a hidden gap comes into view

The trouble surfaced indirectly. In 2021, a team of physicists posted a paper whose ideas depended on the generalized quantum Stein’s lemma. Marco Tomamichel, a professor at the National University of Singapore, noticed something was off. The issue did not stop with the new paper. Tracing the logic backward led him and others to the original theorem itself.

As Masahito Hayashi, a co-author of the new study, later explained, “Later, Berta and his colleagues published a paper explicitly describing the gap and its consequences.” What had once seemed like a settled result was now revealed to rest on a proof that was incomplete.

This discovery sent ripples through the field. The lemma was not a niche curiosity. It was described by Hayashi as “foundational in quantum resource theory,” and many papers depended on it. If the proof contained a gap, then the certainty of all those dependent results was suddenly in question.

Researchers responded quickly. Some attempted to patch the argument, hoping the original claim could still be salvaged. One such effort was posted by Yamasaki and Kuroiwa, but that proof, too, turned out to contain a gap. The situation was unsettling. Either the theorem needed a correct proof, or the field would have to rethink a decade’s worth of conclusions.

A second-hand warning and a false assumption

During this period, Hayashi was deeply engaged in quantum information theory, testing various quantum hypotheses. Yet he was not immediately drawn into the controversy. His understanding of the problem came indirectly, and crucial details were missing.

“I initially heard about this issue second-hand, and the person conveying it did not accurately specify the five conditions imposed on the composite alternative hypothesis,” Hayashi recalled. Those five conditions were essential to the theorem. Without them, counterexamples could easily be constructed.

“For instance, if the composite hypothesis is not convex, it is easy to construct counterexamples—yet that condition was not communicated while the closedness of the composite hypothesis is one of the five conditions.”

Based on this incomplete information, Hayashi reached a pessimistic conclusion. He believed that the generalization proposed in 2008 could not possibly hold. As a result, he did not attempt to repair the theorem. For a time, the problem remained something he was aware of, but not actively pursuing.

A workshop in Granada and a change of mind

Everything shifted in May 2024 at an international workshop held at the University of Granada. There, Hayashi listened as his future co-author, Hayata Yamasaki, carefully laid out the conjectured generalized quantum Stein’s lemma. This time, the explanation included all five conditions, presented clearly and precisely.

“At this workshop, my co-author Hayata Yamasaki explained the conjectured generalized quantum Stein’s lemma and, crucially, stated the five conditions on the composite alternative hypothesis correctly and clearly,” Hayashi said.

The effect was immediate. With the full structure of the claim finally visible, Hayashi saw that his earlier pessimism might have been misplaced. “Because the explanation was easy to follow, Hayashi began—during the latter half of the workshop and while traveling to the next meeting—to examine whether the claim could be proved.”

The problem that had once seemed impossible now looked approachable. The theorem did not need to be abandoned. It needed careful repair.

Chasing a proof through travel and exchange

Hayashi’s first approach drew on Schur duality, a mathematical concept rooted in group representation theory. Instead of following earlier strategies exactly, he made a deliberate choice. He excluded one of the five technical conditions usually assumed, namely the idea that the allowed set of states remains valid after part of the system is discarded.

The result was a rough proof, incomplete but promising. Hayashi sent it to Yamasaki, initiating a back-and-forth exchange that refined the argument. “After developing a rough proof of the theorem, I sent it to Yamasaki for checking,” Hayashi said. “After several rounds of exchange, the proof was completed and we moved on to generalizing the resource conversion theory.”

The collaboration became a true partnership. During the next phase, Yamasaki articulated the main ideas for extending the theory, while Hayashi refined and modified them. Step by step, the argument grew stronger, shedding unnecessary assumptions and closing logical gaps.

Facing the eigenvalue obstacle

Even with the core proof in place, challenges remained. Hayashi presented the work at a seminar organized by Tomamichel, the very researcher who had first identified the flaw years earlier. This was a pivotal moment. Tomamichel confirmed the correctness of the proof, but with an important caveat.

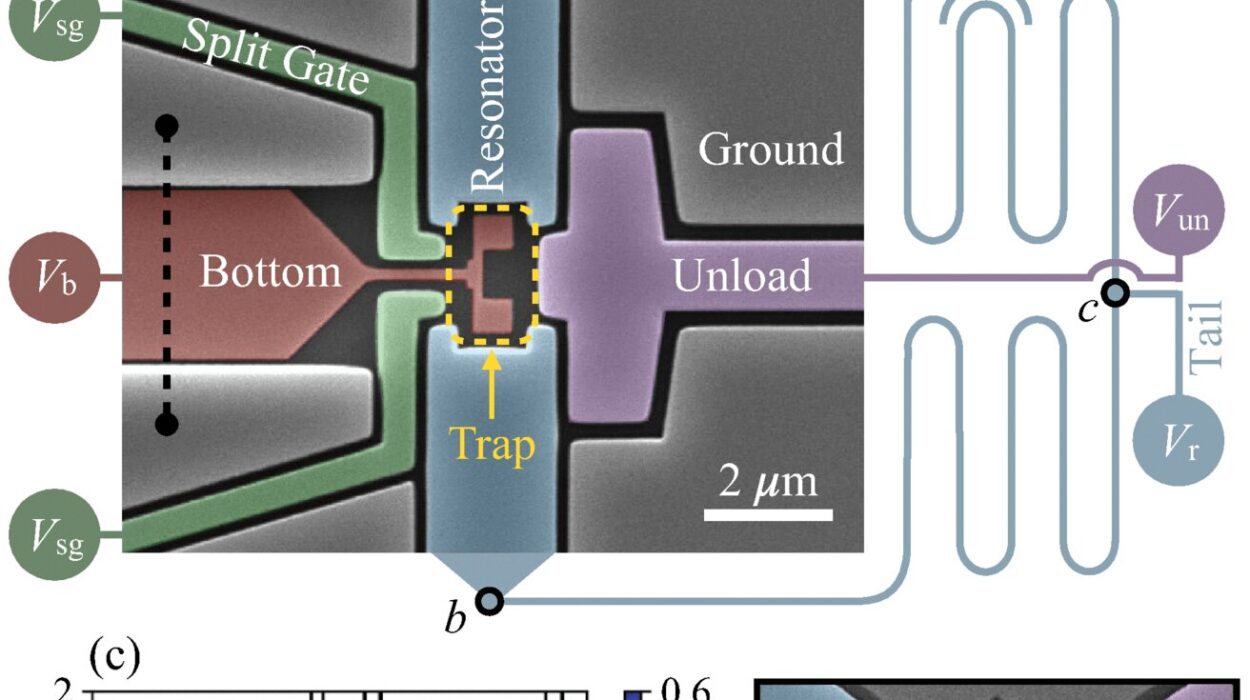

“At this stage, the proof still assumed one of the five conditions: closure under permutations,” Hayashi explained. That assumption was tied to a mathematical procedure known as pinching, which depends on controlling the number of distinct eigenvalues associated with a quantum system.

Eigenvalues, in this context, capture essential properties of matrices describing quantum states. If their number grows too quickly as systems become larger, the proof can break down. Traditionally, permutation-closure ensured that the number of eigenvalues remained manageable, growing only polynomially with the number of copies.

To remove this assumption, Hayashi and Yamasaki turned to a technique introduced in an earlier paper. “To handle the case where the number of eigenvalues is not polynomial, we used a technique introduced in an earlier paper, which works by replacing a matrix with another matrix whose number of eigenvalues is polynomial and then carrying out the argument,” Hayashi said.

This move was decisive. It eliminated the need for permutation-closure altogether. With all unnecessary assumptions removed and the gap fully repaired, the researchers submitted the final version of their work to Nature Physics.

Restoring a quantum ‘second law’

The repaired theorem does more than fix a technical oversight. It restores confidence in a principle that echoes one of the most powerful ideas in physics. According to Hayashi and Yamasaki, quantum resources obey a law similar to the second law of thermodynamics. Not every transformation is possible, and those that are possible follow strict rules about rates and limitations.

“With this result, we succeeded in re-establishing the ‘second law’ in quantum resource theories,” Hayashi said. “In other words, the conversion of various types of quantum resources can—under an appropriate class of conversion rules—now be discussed in a unified way in terms of conversion rates.”

This unification matters because resource theories are used to understand what quantum technologies can realistically achieve. Quantum computers, sensors, and communication devices all rely on carefully managing limited quantum resources. A flawed theorem at the foundation would cast doubt on predictions about their performance.

By repairing the generalized quantum Stein’s lemma, Hayashi and Yamasaki have provided a more reliable mathematical basis for designing and analyzing these technologies. Their work clarifies which transformations are fundamentally allowed and which are not, under clearly stated and justified conditions.

Why this repair matters for the future of quantum technology

At first glance, fixing a gap in a mathematical proof may seem like an internal concern for theorists. In reality, its consequences reach far beyond chalkboards and equations. Quantum engineers depend on theoretical guarantees to optimize algorithms and to predict the limits of their systems. If those guarantees are shaky, progress slows.

The updated version of the generalized quantum Stein’s lemma offers renewed certainty. It tells researchers that the rules governing quantum resource conversion are consistent and dependable. It allows different types of resources to be compared and transformed within a single, coherent framework.

Hayashi and Yamasaki are already looking ahead. As Hayashi noted, “As a continuation of this work, we plan to further develop resource theories for dynamical resources and have already obtained some results in this direction.”

The story of this theorem is a reminder of how science advances. Even widely accepted results can hide subtle flaws. What matters is not the absence of mistakes, but the willingness to confront them openly and repair them carefully. In doing so, this work strengthens the foundations on which future quantum technologies will be built, ensuring that their remarkable promises rest on solid ground rather than fragile assumptions.

More information: Masahito Hayashi et al, The generalized quantum Stein’s lemma and the second law of quantum resource theories, Nature Physics (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41567-025-03047-9