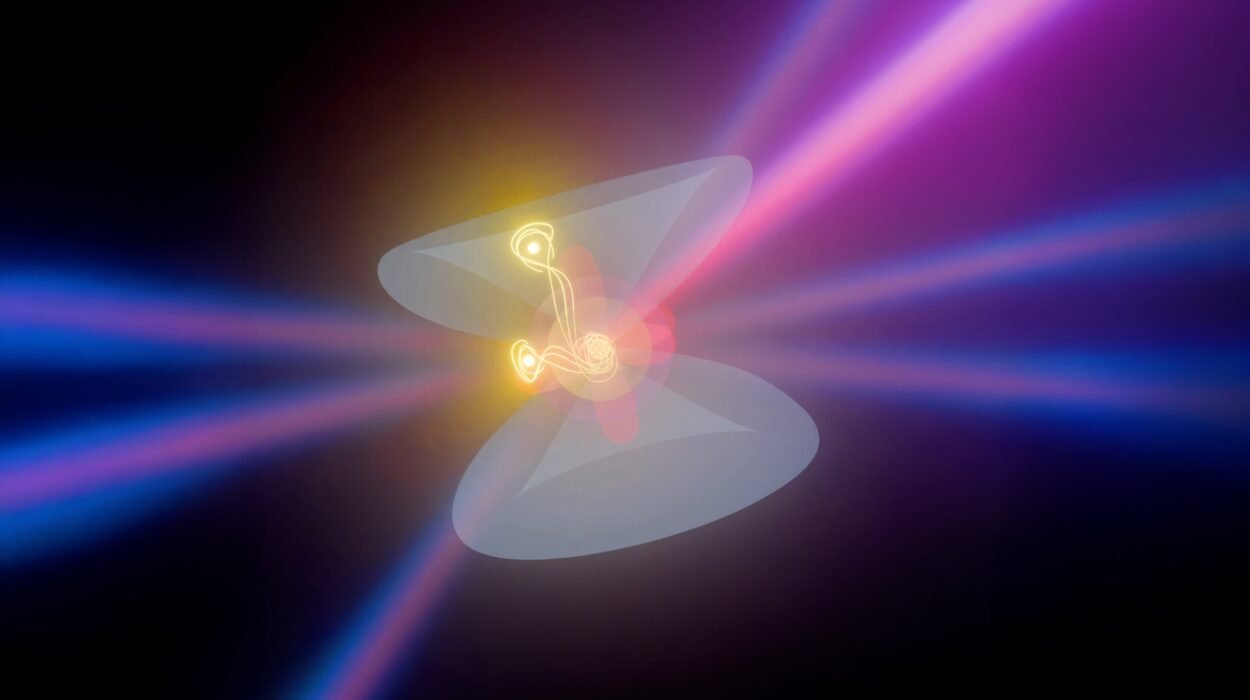

Separate two superconductors with a thin barrier, and physics does something quietly astonishing. The property that allows electricity to flow without resistance does not stop at the edge of the material. Instead, it seeps across the divide, synchronizing electrons on both sides as if distance were an illusion. This strange cooperation is known as a Josephson junction, a device so central to modern quantum technology that advances related to it were honored with the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics.

For decades, the rules seemed clear. A Josephson junction required two superconductors, each supplying its own perfectly paired electrons. Without that symmetry, the effect should vanish. And yet, a new experiment has revealed behavior that refuses to follow that expectation. An international team has observed electrical signatures that look unmistakably like a Josephson junction, even though only one superconductor was present.

The finding suggests that superconductivity does not merely influence its neighbor in a faint or superficial way. Under the right conditions, it can awaken something far more organized and powerful on the other side of a barrier. The work, published in Nature Communications, opens a surprising window into how quantum materials might be simplified, reshaped, and possibly made more robust for future technologies.

A Junction with a Missing Half

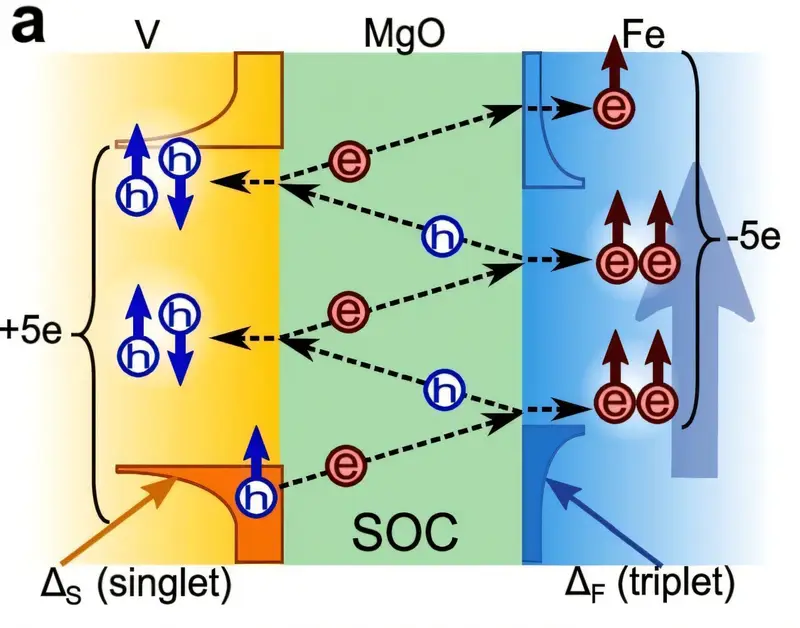

At the center of the experiment was a carefully constructed device. On one side sat vanadium, a metal known for its superconducting properties. On the other side was iron, a material famous not for superconductivity but for ferromagnetism, the same phenomenon that gives permanent magnets their strength. Between them lay a thin layer of magnesium oxide, forming a barrier that electrons could not easily cross.

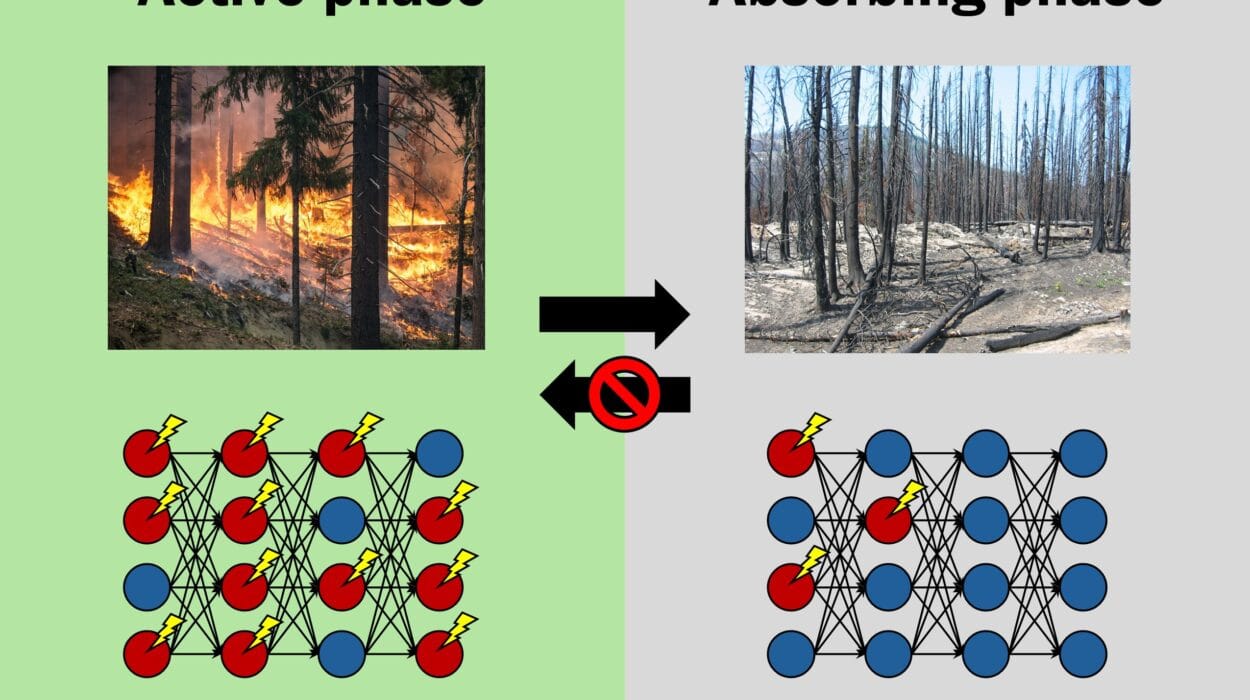

According to long-standing theory, superconductivity can leak slightly into neighboring materials. This so-called proximity effect has been studied for years. But what the team observed went far beyond a weak echo of superconducting behavior. The vanadium appeared to induce strong electron pairing inside the iron, enough to produce synchronized electrical behavior that closely mimicked a Josephson junction.

In other words, the iron began to act as if it were a superconductor in its own right, even though it was never intended to be one. The result was not just a subtle modification of iron’s properties, but a coordinated response that sent signals back across the barrier, completing a kind of quantum conversation between the two materials.

A River, an Army, and an Unexpected Militia

To describe what they saw, the researchers turned to metaphor. “A typical Josephson junction with two superconductors is like two army battalions marching in step along opposite banks of a river. In our experiment, there was only one battalion—yet it’s as if its marching caused citizens on the other side to form a militia and begin marching to the beat of a different drum,” says the study’s co-corresponding author, Igor Žutić, SUNY Distinguished Professor in the Department of Physics in the University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences.

The image captures both the surprise and the subtlety of the effect. Vanadium set the rhythm, but iron did not simply copy it. Instead, iron organized its own internal motion, forming electron pairs in a way that was distinct from the superconductivity that initiated the process. Despite this difference, the two sides remained synchronized well enough to behave as a single quantum system.

The experiments were conducted in the laboratory of co-corresponding author Farkhad Aliev, Ph.D., professor of condensed matter physics at the Autonomous University of Madrid. The collaboration spanned institutions across Spain, France, Romania, China, and the United States, bringing together expertise that allowed theory and experiment to meet in an especially striking way. The measurements confirmed ideas that had existed in theoretical form for decades, but had never before been observed directly.

Listening to the Noise Beneath the Current

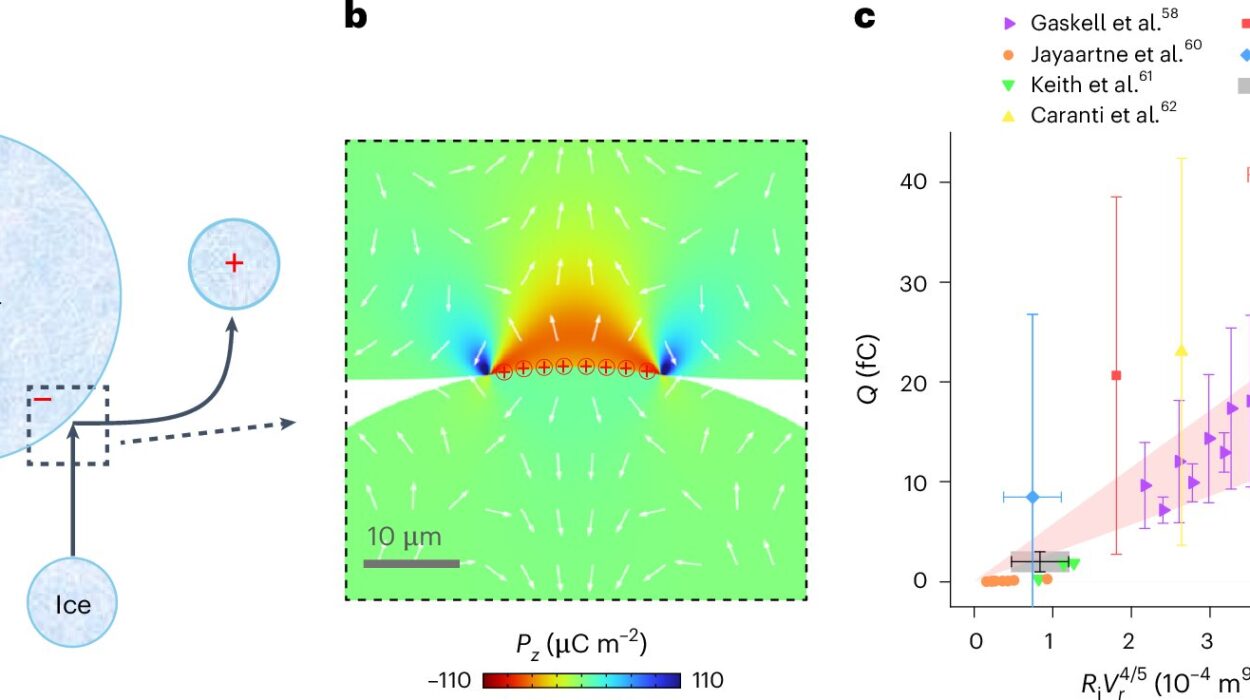

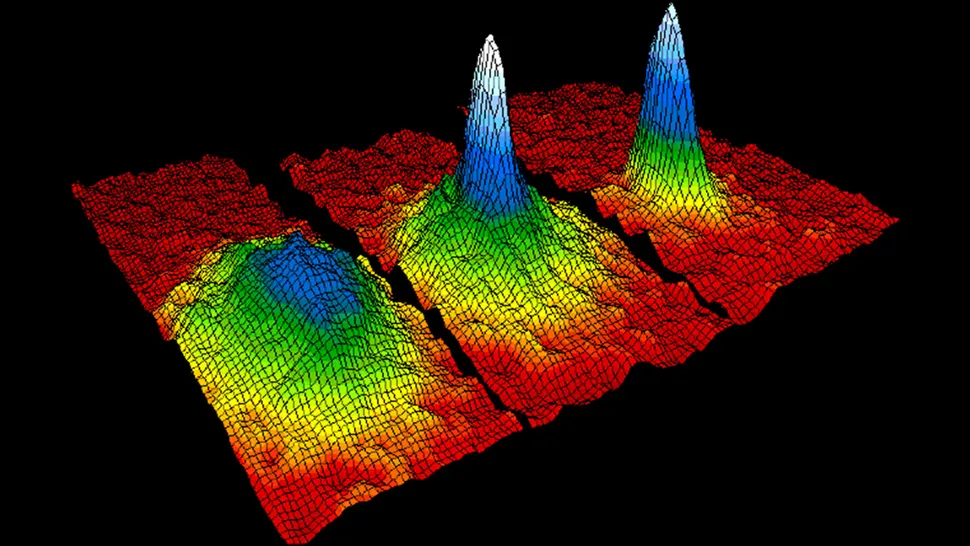

To understand how the team detected this hidden synchronization, it helps to rethink what electrical current really is. At everyday scales, electricity seems smooth and continuous, like water flowing from a tap. But look closer, and that flow breaks down into discrete events, individual electrons arriving in tiny, irregular bursts.

“These small, unavoidable fluctuations in electron flow are called noise, and by listening to them we can learn how charge moves through a material,” says Jong Han, Ph.D., professor in the UB Department of Physics and a co-author of the study.

Rather than being a nuisance, this noise becomes a source of insight. By carefully analyzing the fluctuations in their vanadium–iron device, the researchers were able to infer how electrons were moving inside the materials. What they found was extraordinary. Inside the iron, electrons were not acting independently. They were traveling in large, highly coordinated groups, a signature of the collective behavior normally associated with superconductivity.

This kind of coordination is exactly what gives a Josephson junction its unique properties. It indicates that electron pairs are moving in lockstep, maintaining a shared quantum phase. Observing this inside iron, a material that should resist such pairing, was a clear signal that something unusual was happening at the quantum level.

When Magnetism and Superconductivity Collide

The result was especially surprising because iron is a ferromagnet, and ferromagnetism and superconductivity are typically incompatible. In conventional superconductors, electrons form pairs with opposite spins, one pointing up and the other pointing down. This opposition allows them to move without resistance. In ferromagnets, however, electrons tend to align their spins in the same direction, like compass needles responding to a magnetic field.

An electron’s spin can be thought of as a tiny magnetic arrow. In iron, most of those arrows point the same way. That alignment should tear apart the delicate opposite-spin pairs required for standard superconductivity. And yet, the experiment showed that iron was somehow able to form electron pairs anyway.

“The iron essentially created a different type of superconductivity from vanadium,” Žutić says. “In other words, the citizens organized in their own way but kept time well enough to march as an army and send their own rhythm back across the river.”

This statement points to the heart of the discovery. The pairing inside iron involved electrons with spins in the same direction, a fundamentally different arrangement from conventional superconductivity. Despite this difference, the pairing was robust enough to support Josephson junction-like behavior, allowing the iron to participate actively in the quantum synchronization rather than passively responding to it.

An Answer That Opens New Questions

While the experimental evidence is compelling, the precise mechanism by which iron managed to sustain these same-spin electron pairs remains an open question. The researchers are continuing to theorize about how such pairing could become strong and stable enough to mimic the behavior of an independent superconductor.

This mystery is not a weakness of the work, but a source of excitement. Same-spin pairing has been discussed in theoretical contexts before, particularly in connection with exotic states of matter. Seeing hints of it emerge in a relatively simple device suggests that new forms of superconductivity might be more accessible than previously thought.

The team is particularly intrigued by the possible implications for topological superconductors. These materials are valued for their resilience. They store quantum information in ways that are less sensitive to local disturbances, protecting delicate quantum states from environmental noise. In such systems, information is tied to global, knot-like properties rather than fragile local details.

“The problem with conventional quantum computers is that even small environmental changes can throw off the spin of their electrons. We want to find a way to essentially lock an electron’s spin into place, and same-spin pairing could hold some answers,” Žutić says.

Why This Discovery Matters

Beyond its theoretical intrigue, the discovery carries practical promise. Josephson junctions are foundational elements of quantum computers, but they often rely on complex fabrication and carefully chosen materials. Demonstrating Josephson-like behavior with only one traditional superconductor hints at the possibility of simpler designs.

There is also an appealing familiarity to the materials involved. Iron and magnesium oxide are not exotic laboratory curiosities. They are already widely used in magnetic computer hard drives and magnetic random-access memory. The idea that such common materials could be combined with superconductors to create new quantum devices suggests a path toward technologies that are not only powerful but also scalable.

“We have added a superconducting twist to commercially viable devices,” Žutić says.

At a deeper level, the research matters because it challenges assumptions about what materials can do when placed in the right quantum environment. It shows that superconductivity is not a rigid identity confined to a select group of elements, but a behavior that can be induced, reshaped, and shared in unexpected ways. By listening carefully to the noise beneath the current, the researchers have revealed a hidden order where disorder was expected, and in doing so, they have expanded the map of what quantum matter can become.

More information: César González-Ruano et al, Giant shot noise in superconductor/ferromagnet junctions with orbital-symmetry- controlled spin-orbit coupling, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64493-w