In a chemistry department in Helsinki, something ordinary and invisible became the focus of a long, patient experiment. The air itself, untreated and unfiltered, drifted through a laboratory where a researcher was trying to do something deceptively simple: catch carbon dioxide without grabbing anything else. No oxygen, no nitrogen, no surrounding noise of the atmosphere. Just CO2, singled out from the crowd.

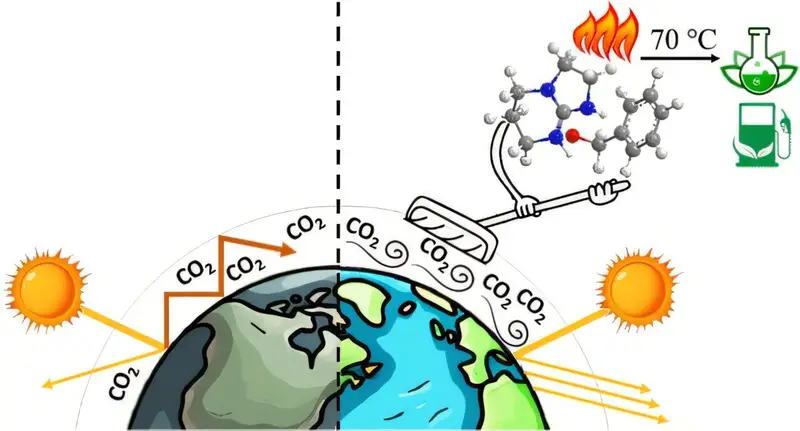

This quiet ambition has now turned into a discovery that feels almost storybook in its simplicity. A new method to capture carbon dioxide directly from the air has been developed at the University of Helsinki, and it does so with a gentleness that sets it apart from existing approaches. The work emerged from the chemistry department, led by Postdoctoral Researcher Zahra Eshaghi Gorji, and it points toward a future where pulling carbon dioxide out of the sky may be less harsh, less costly, and more reusable than before.

A Compound That Knows What to Ignore

At the heart of the discovery is a compound formed from a superbase and an alcohol. That description may sound technical, but its behavior is strikingly selective. When exposed to ambient air, the compound absorbs carbon dioxide while leaving the rest of the atmosphere untouched.

Tests carried out in Professor Timo Repo’s group revealed just how effective this selectivity is. One gram of the compound can absorb 156 milligrams of carbon dioxide directly from untreated ambient air. It does not react with nitrogen, oxygen, or other atmospheric gases. That focus gives it an edge over current carbon capture methods, whose capacity it clearly outperforms.

The result feels almost like a handshake between chemistry and restraint. Instead of forcing reactions at extreme conditions or filtering massive volumes of gas, the compound waits, absorbs what it needs, and ignores the rest.

Letting Go Without Fire

Capturing carbon dioxide is only half the story. Releasing it again, cleanly and efficiently, has long been one of the greatest challenges in carbon capture technology. Many existing compounds cling so tightly to CO2 that freeing it requires enormous amounts of energy. Typically, releasing carbon dioxide from current compounds demands heat above 900° C, a process that is costly and energy-intensive.

This new compound behaves differently. The carbon dioxide it captures can be released by heating the compound to 70° C for 30 minutes. From this mild process, clean CO2 is recovered and can be recycled.

The ease of this release is described as the key advantage of the compound. It suggests a gentler cycle of capture and release, one that does not depend on extreme temperatures or punishing conditions. Instead of burning energy to undo what has been done, the compound loosens its grip with relative ease.

A Material That Endures the Cycle

In the real world, usefulness depends on repetition. A material that works once but fails quickly is little more than a laboratory curiosity. Gorji and her colleagues paid close attention to how the compound behaved over many cycles of capture and release.

The results were encouraging. According to Gorji, the compound retained 75% of its original capacity after 50 cycles and 50% after 100 cycles. Even as its performance gradually declined, the fact that it continued to function across dozens of uses suggests a resilience that is essential for practical applications.

This durability turns the compound from a single-use solution into a reusable tool, one that can be asked to do its job again and again without being discarded after a short lifespan.

A Year of Testing, One Discovery at a Time

The compound did not appear overnight. Gorji describes a long process of experimentation, testing a number of bases in different combinations. The work stretched over more than a year, filled with trial and error, patience, and careful observation.

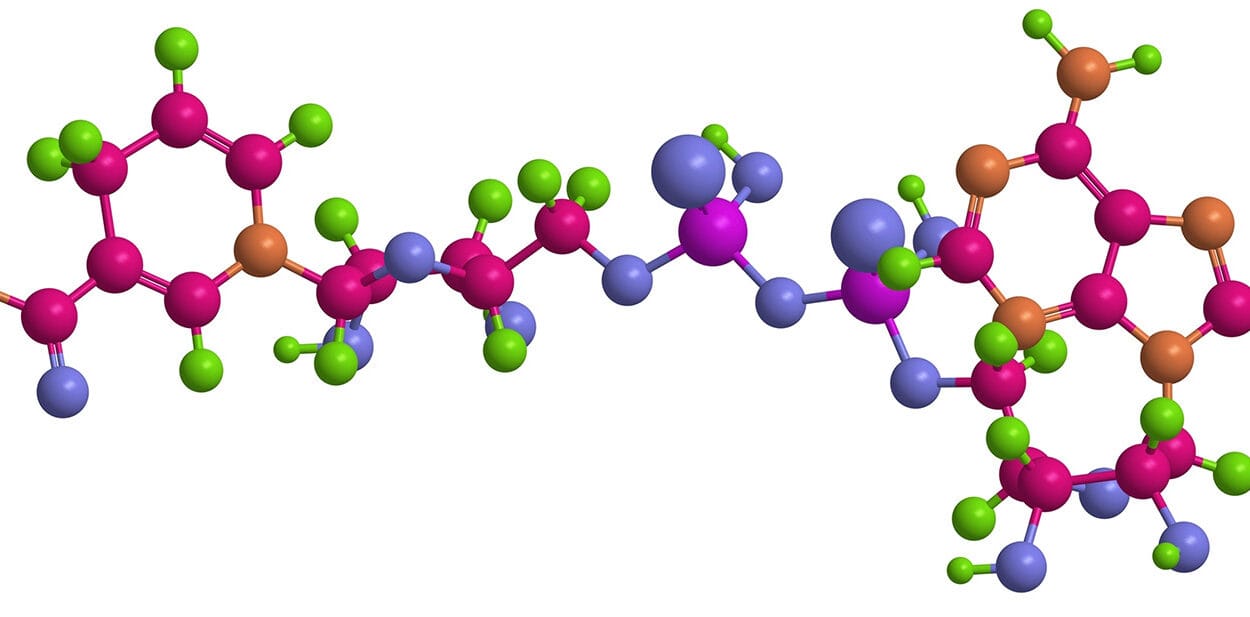

Out of these experiments, one base stood out as the most promising: 1,5,7-triazabicyclo [4.3.0] non-6-ene, known as TBN. This base was developed in Professor Ilkka Kilpeläinen’s group and became the foundation for the final compound when combined with benzyl alcohol.

The discovery was not a sudden flash of insight but a gradual narrowing of possibilities. Each experiment eliminated what did not work and sharpened the focus on what did. In that sense, the compound carries within it the quiet history of many failed attempts that eventually pointed the way forward.

Affordable Chemistry With a Human Scale

Cost and safety often determine whether a scientific breakthrough remains confined to academic journals or moves into the world. Gorji emphasizes that the components of the compound are not exotic or prohibitively expensive.

“None of the components is expensive to produce,” notes Gorji.

Beyond affordability, the compound is also non-toxic. That combination matters. A material designed to interact with air on a large scale cannot pose risks to people or the environment around it. The fact that this compound avoids toxicity while remaining effective adds to its promise as a practical solution rather than a theoretical one.

From Grams to Something Bigger

So far, the compound has lived its life in small quantities, measured in grams and tested under controlled laboratory conditions. The next chapter moves it closer to the scale where it could make a tangible difference.

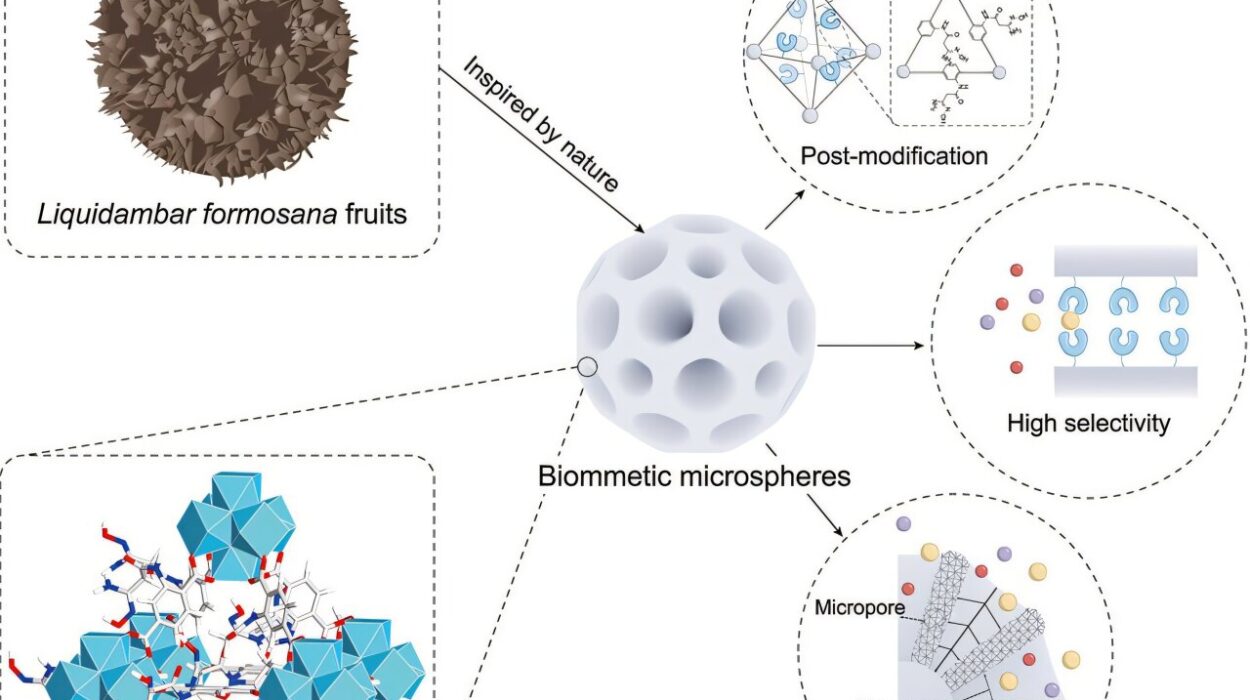

The compound will now be tested in pilot plants at a near-industrial scale. To make this leap, it must change its physical form. A solid version of the currently liquid compound needs to be created so it can be used effectively in larger systems.

Gorji outlines the idea guiding this transformation. “The idea is to bind the compound to compounds such as silica and graphene oxide, which promotes the interaction with carbon dioxide,” says Gorji.

This step is about giving the compound structure and support, anchoring it to materials that help it meet carbon dioxide more efficiently. It is a move from the delicate environment of a laboratory bench to the rougher demands of real-world operation.

A Study Shared With the World

The research has been published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, placing it into the broader scientific conversation about carbon capture and climate solutions. Publication marks not an end but an invitation, allowing other scientists to examine, test, challenge, and build upon the findings.

What stands out in this work is not only the numbers or the chemistry but the philosophy behind it. Rather than overpowering nature with extreme conditions, the compound works quietly within the bounds of modest temperatures and repeated use.

Why This Research Matters

Carbon dioxide in the air is one of the defining challenges of our time, but capturing it has often come at a high energetic and economic cost. This research points toward a different path. A compound that selectively absorbs CO2 from untreated ambient air, releases it at relatively low temperatures, and can be reused dozens of times changes the conversation about what carbon capture can look like.

The significance lies not in a single number or reaction but in the balance the compound achieves. It combines effectiveness with restraint, durability with simplicity, and innovation with affordability. The fact that it avoids reacting with other atmospheric gases, releases CO2 without extreme heat, and relies on non-toxic, cost-effective components makes it more than an academic success.

As the compound moves toward pilot-scale testing, it carries with it the possibility of carbon capture systems that are gentler, more efficient, and more realistic to deploy. This research matters because it shows that progress does not always require louder machines or hotter fires. Sometimes, it begins with a molecule that quietly breathes in the air and knows exactly what it is looking for.

More information: Zahra Eshaghi Gorji et al, Direct Air Capture: Recyclability and Exceptional CO2 Uptake Using a Superbase, Environmental Science & Technology (2025). DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5c13908