Ammonia is everywhere and almost nowhere at the same time. It is colorless, easy to miss, and yet deeply woven into modern life. It helps grow the food that fills fields and markets. It appears in cleaning products under kitchen sinks. It plays a role in industrial materials powerful enough to reshape landscapes. Made from nitrogen and hydrogen, ammonia looks simple on paper, NH3, but its impact stretches across agriculture, industry, and the environment.

For more than a century, the world has relied on a single dominant method to make it. The Haber-Bosch process, an industrial triumph of chemistry, forces nitrogen and hydrogen to react by pushing them to extremes. High temperatures. Crushing pressures. Massive energy input. It works, but it comes at a cost that has become harder to ignore.

As the researchers behind a new study plainly state, “The Haber–Bosch process for ammonia synthesis contributes up to ~3% of global greenhouse gas emissions.” That number hangs in the air like a challenge. Ammonia is essential, but the way it is made is part of the climate problem. The question that has lingered for years is whether there is another way.

A Glimmer of Light in an Old Problem

At Stanford University School of Engineering, Boston College, and several other institutions, researchers began looking at ammonia through a different lens, quite literally. Instead of heat and pressure, they asked what light could do. Not intense industrial furnaces or sealed reactors, but visible light, the kind that arrives every day from the sun.

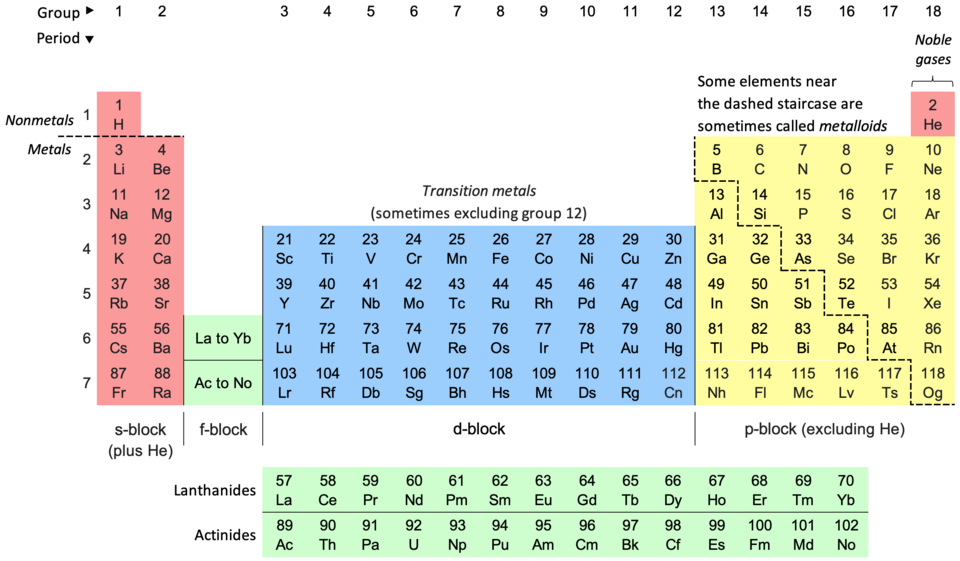

Their idea centered on catalysts, materials that speed up chemical reactions without being consumed. The team focused on plasmonic catalysts, materials known for their strong interactions with light. When light hits them, electrons respond in ways that can change how chemical reactions unfold.

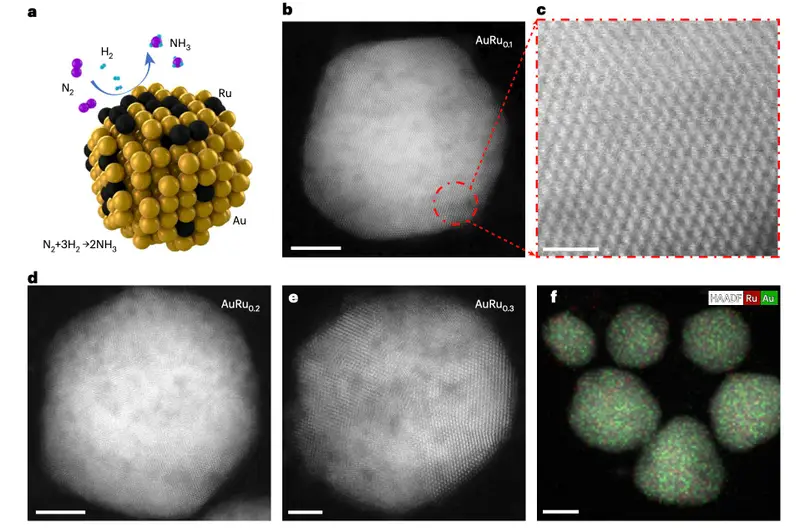

“Plasmonic catalysts strongly concentrate light and can alter the reaction intermediates via out-of-equilibrium processes, providing the potential for an alternative, less-energy-intensive pathway to synthesize ammonia,” the researchers wrote. Then came the statement that turned heads. “We show that gold-ruthenium (AuRu) bimetallic nanoparticles can synthesize ammonia at room temperature and pressure using visible light.”

Room temperature. Normal pressure. No industrial extremes. The words carried a quiet but profound disruption.

Tiny Particles, Big Possibilities

The catalysts themselves are almost unimaginably small. They are nanoparticles made of gold and ruthenium blended together in different ratios, forming tiny AuRu alloys. Each particle is a miniature stage where light, hydrogen, and nitrogen meet.

When light shines on these particles, something remarkable happens. The nanoparticles respond, absorbing and concentrating the light, and in doing so they speed up the chemical steps that transform nitrogen and hydrogen into ammonia. The reaction that once demanded harsh industrial conditions begins to unfold calmly, under ambient air and temperature.

To see what was happening inside these tiny systems, the researchers turned to infrared spectroscopy. By sending an infrared beam through the reacting materials and measuring how the light passed through, they could track the chemical intermediates forming and changing in real time.

Their measurements told a clear story. “We create AuRu alloys with varying compositions and achieve ammonia production rates of ~60 μmol per gram of catalyst bed per hour,” the authors wrote. This was not a theoretical prediction or a fleeting signal. It was measurable ammonia, formed under conditions that once seemed impossible for this reaction.

Even more telling was what the spectroscopy revealed about the process itself. “In situ infrared spectroscopy reveals that light accelerates the hydrogenation of nitrogen intermediates compared to conventional thermal catalysis.” Light was not just present. It was actively shaping the reaction.

Watching Chemistry Take a New Path

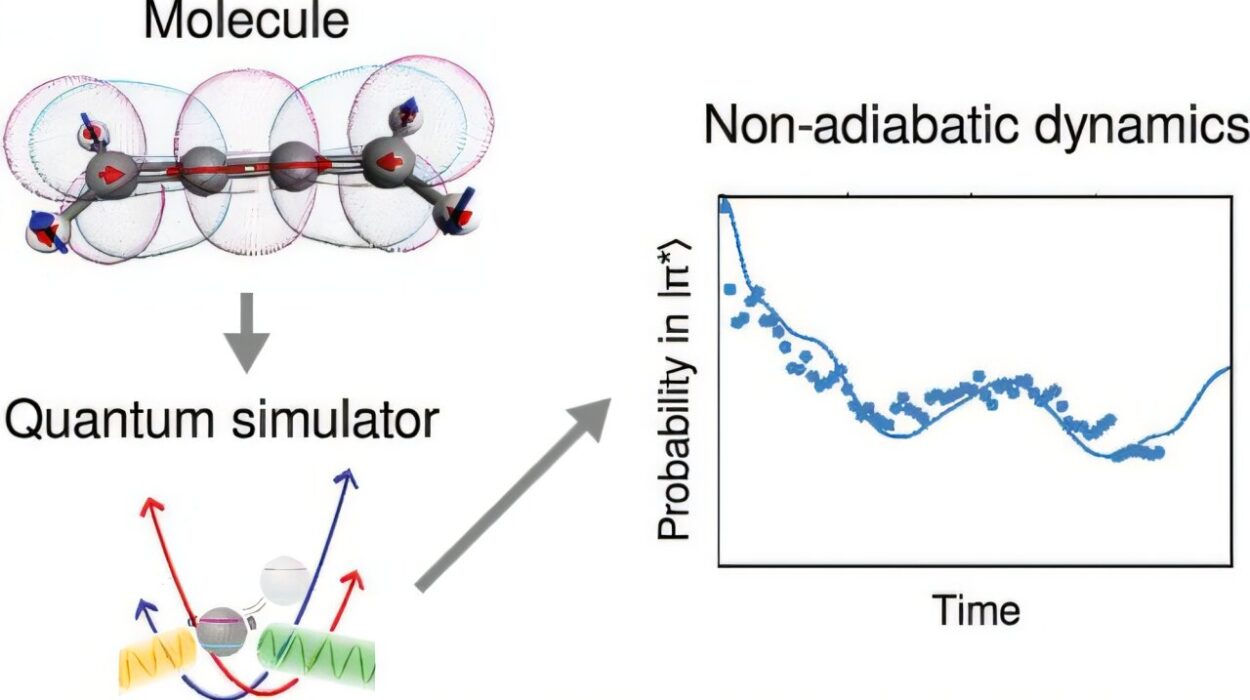

The excitement did not stop with experimental results. To understand why the catalysts worked so well, the researchers ran computer simulations that allowed them to follow electrons and atoms step by step.

What they discovered was unexpected and deeply intriguing. The ammonia was not being formed by brutally breaking apart nitrogen molecules, as in traditional industrial methods. Instead, the reaction followed a gentler, more gradual path.

“Through computational modeling, we demonstrate that photo-excited electrons enable associative hydrogenation pathways for nitrogen activation rather than direct nitrogen–nitrogen bond breaking,” the team wrote. In other words, light energized electrons in the nanoparticles, and those energized electrons helped hydrogen atoms attach to nitrogen step by step.

This shift in mechanism mattered because it lowered the barrier that normally makes nitrogen so difficult to work with. Nitrogen molecules are famously stable, resistant to change. The simulations showed that light and hydrogen worked together to overcome this resistance.

“This light-assisted mechanism requires both hydrogen and light working together to overcome the nitrogen activation barrier, mimicking how biological enzymes produce ammonia naturally and providing fundamental insights for developing sustainable, energy-efficient chemical synthesis,” the researchers explained.

In a subtle and elegant way, the reaction began to resemble processes that already exist in nature.

Echoes of Biology in a Metal Catalyst

In soils and living systems, ammonia is produced without furnaces or pressure vessels. Biological enzymes carry out the task delicately, using complex pathways that avoid brute force. The fact that a man-made catalyst, activated by light, could echo this biological approach was striking.

The resemblance was not superficial. The associative hydrogenation pathway observed in the simulations mirrored the gradual, stepwise transformations seen in natural ammonia production. It suggested that sustainability in chemistry might come not from overpowering nature, but from learning its rhythms.

This realization reframed the AuRu nanoparticles as more than just a clever catalyst. They became a bridge between industrial chemistry and biological inspiration, between sunlight and synthesis, between modern technology and ancient processes.

Rethinking an Industrial Giant

Ammonia production is one of the pillars of modern industry. Any suggestion of change carries enormous weight. The Haber-Bosch process has fed populations and supported economies, but it has also locked ammonia into an energy-hungry model.

The new approach described in this research does not claim to replace existing systems overnight. Instead, it opens a door that had long seemed sealed. It shows that ammonia can be made under ambient conditions, that light can play a central role, and that catalysts can guide reactions along gentler paths.

The initial results are described as highly promising, particularly because the reaction proceeds much faster than many other previously proposed low-energy approaches. The combination of experimental evidence and computational insight provides a rare clarity about both what happens and why it happens.

From Laboratory Insight to Real-World Impact

The researchers are careful not to overstate what comes next. Their catalysts have been tested in controlled settings, and further refinement will be needed. Yet the implications ripple outward.

Future energy researchers could take inspiration from this work, exploring similar light-driven methods not only for ammonia, but for other valuable chemical products. The idea that visible light and carefully designed nanoparticles could drive essential reactions suggests a new design philosophy for chemical synthesis.

Over time, these catalysts could be tested in broader environments, scaled up, and adapted. The vision extends from large industrial plants to smaller chemical facilities, places where producing ammonia more cleanly could have immediate environmental benefits.

Why This Research Matters

This research matters because it challenges one of the most energy-intensive chemical processes on Earth without dismissing its importance. Ammonia is not optional. It is a cornerstone of agriculture and industry. The problem has never been whether to make it, but how.

By demonstrating that ammonia can be synthesized at room temperature and normal pressure using visible light, the researchers offer a glimpse of a future where necessity does not automatically mean pollution. They show that chemistry does not have to rely solely on extremes to be effective.

Perhaps most importantly, the work reveals a deeper lesson. Sustainable solutions may emerge not from fighting nature, but from understanding and echoing its strategies. In the gentle interplay of light, metal, hydrogen, and nitrogen, a new story of ammonia begins to take shape, one where energy efficiency, environmental responsibility, and scientific curiosity move forward together.

More information: Lin Yuan et al, Atmospheric-pressure ammonia synthesis on AuRu catalysts enabled by plasmon-controlled hydrogenation and nitrogen-species desorption, Nature Energy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41560-025-01911-9.