In the broad sweep of European prehistory, change often arrived like a tidal wave. New people came, new customs took root, and ancient ways faded into memory. But in a stretch of land that today includes Belgium, the Netherlands, and parts of Germany, something extraordinary happened. Time seemed to hesitate.

Researchers at the University of Huddersfield, working within an international network led by David Reich at Harvard University, have uncovered a remarkable story hidden in ancient DNA. Their findings, published in Nature, reveal that in this watery, resource-rich region of Europe, hunter-gatherers survived for thousands of years longer than anywhere else on the continent. Even more strikingly, the research shines a light on the pivotal role of women in shaping this quiet resistance to change.

The discovery did not come from dusty chronicles or carved stones. It emerged from the very code of life itself.

Reading the Past in Human Genomes

The team analyzed complete human genomes from individuals who lived between 8500 and 1700 BCE. These were not isolated samples but part of a sweeping genetic investigation across a region long considered central to Europe’s prehistoric transformations.

This era was one of profound upheaval. Before borders divided nations, people moved freely across landscapes. Entire populations migrated, bringing with them new tools, new languages, new beliefs, and new genes. Over time, these waves of movement shaped what we now recognize as the genetic foundation of modern Europeans.

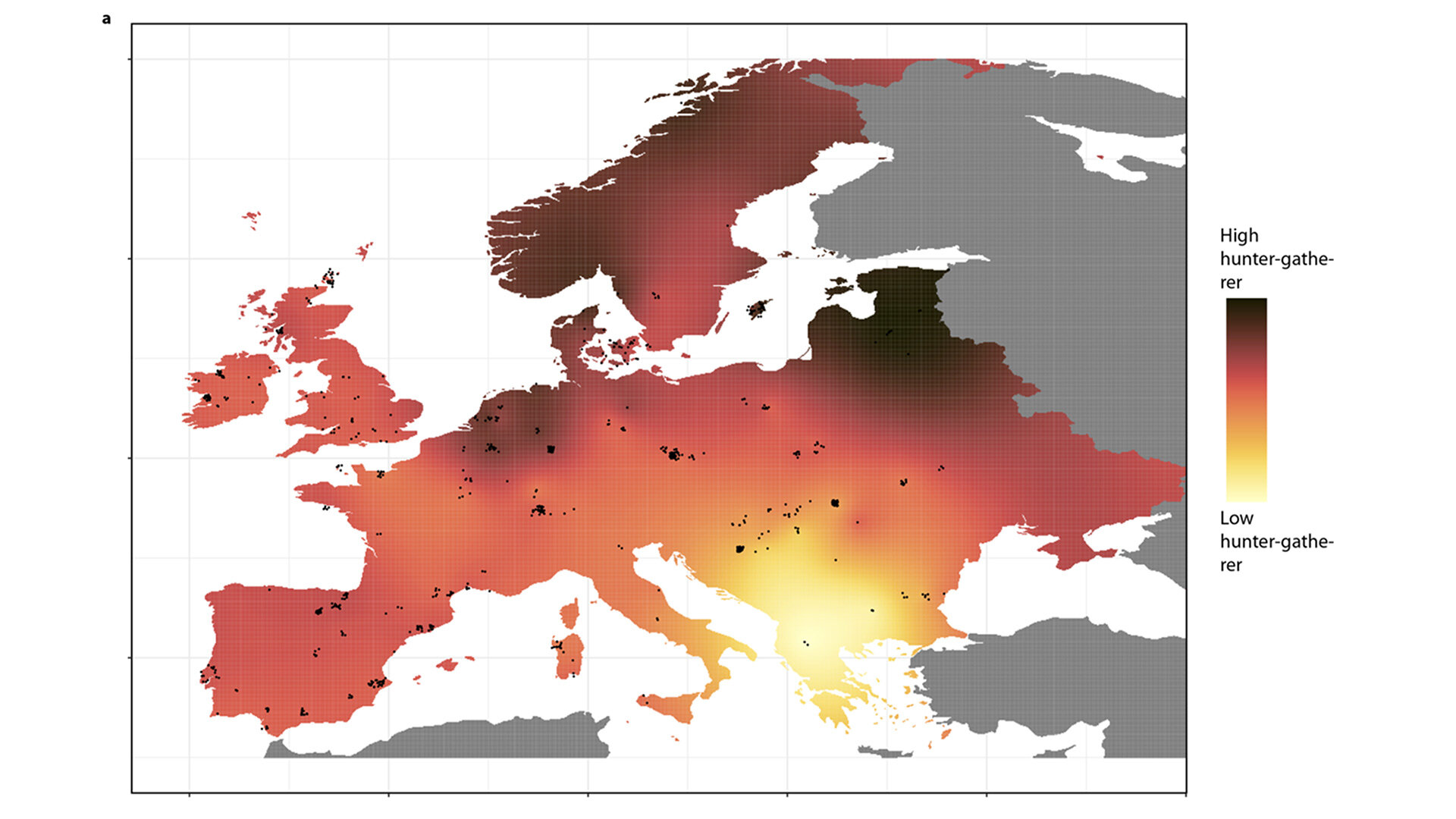

Today, nearly all Europeans carry traces of three ancestral components. There is the hunter-gatherer component, rooted in the continent’s earliest inhabitants. There is the Neolithic component, brought by the first farmers arriving from the Near East. And there is a third layer linked to pastoralists from Russia, who spread later across Europe.

In most regions, these layers stacked one upon another in clear genetic shifts. But in the wetlands and river valleys of this northwestern corner, the pattern told a different story.

When Farming Arrived but Didn’t Take Over

Around 4500 BCE, farming reached this region. Across much of Europe, the arrival of agriculture transformed societies. Genetic signatures changed dramatically as farming populations mixed with or replaced local hunter-gatherers.

But here, something unexpected happened.

The genetic evidence shows that the introduction of farming did not cause a sweeping demographic replacement. Instead of a dramatic shift, there was only minimal genetic input from incoming farmers. The local hunter-gatherer communities did not disappear. They adapted, selectively adopting farming practices while maintaining much of their traditional way of life.

It was not a simple case of newcomers overwhelming the old. It was more subtle. More human.

The region’s riverine wetlands and coastal areas were rich in natural resources. Fish, plants, and wildlife provided reliable sustenance. This abundance may have allowed local communities to adopt farming gradually, on their own terms. They could experiment without surrendering their identity.

And hidden within the genetic data was a fascinating pattern that gave this story an intimate dimension.

The Quiet Power of Women

The genomic clues suggest that when farming communities entered the region, the genetic exchange came mostly through women.

The evidence points to a pattern in which women from farming groups married into local hunter-gatherer communities. They carried with them not only their genes but also their knowledge of agriculture. Through marriage and daily life, they transmitted skills, techniques, and cultural practices.

This was not a mass migration of entire farming populations replacing local people. It was something gentler. A blending at the household level. A transfer of knowledge across family lines.

In this way, farming entered the region through relationships rather than conquest. The change was uneven, localized, and shaped by social bonds. The incoming women acted as bridges between two worlds.

For centuries, perhaps even millennia, this pattern held. The high levels of hunter-gatherer ancestry remained strong in the region, especially in what is now Belgium and the Netherlands. While neighboring areas underwent rapid genetic transformation, these wetlands preserved a different trajectory.

Professor John Stewart of Bournemouth University described the region as almost suspended in time. The expected sharp divide between hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists simply did not appear. Instead, the landscape seemed to soften the transition, as though history itself moved more slowly among the rivers and marshes.

The Moment Everything Realigned

This prolonged persistence of hunter-gatherer ancestry lasted until around 2500 BCE, at the end of the Neolithic period. Then, once again, Europe shifted.

New groups spread across the continent, and this time the mixing was more complete. The incoming populations blended thoroughly with the local communities. The genomic story of this northwestern region finally realigned with neighboring areas.

After thousands of years of gradual adaptation and selective exchange, the genetic landscape transformed more decisively. The era of prolonged hunter-gatherer dominance came to an end.

But by then, the region had already written a unique chapter in Europe’s deep past.

Ancient DNA and the Surprise of the Familiar

What makes this discovery especially striking is its setting. These findings did not come from a remote or isolated corner of the globe. They emerged from what many consider the very heartland of Europe.

Dr. Maria Pala, who supervised the work at the University of Huddersfield, emphasized how unexpected the results were. Ancient DNA studies often reveal surprises in distant or unexplored regions. But here, in a place long studied and central to European prehistory, the genetic record still held secrets.

The research was carried out by Alessandro Fichera and Dr. Francesca Gandini, under the supervision of Dr. Pala, Professor Martin B. Richards, and Dr. Ceiridwen Edwards, within the Archaeogenetics Research Group. They collaborated closely with archaeologists at the Université de Liège, who excavated and managed the ancient human samples, and with paleoecologists who helped interpret the environmental context.

Together, they demonstrated the extraordinary power of ancient DNA studies. With each genome sequenced, the past becomes less abstract. It gains texture, nuance, and human depth.

Why This Story Matters

This research reshapes how we think about one of the most transformative periods in human history. The shift from hunting and gathering to farming is often portrayed as a sweeping revolution, a clean break between old and new. But here we see something far more complex.

In this region of Europe, change was not an avalanche. It was a conversation.

Local hunter-gatherers did not simply vanish under the weight of agricultural expansion. They negotiated their future. They adopted useful innovations while preserving much of their genetic and cultural identity. The environment itself, rich in natural resources, gave them the flexibility to do so.

Perhaps most importantly, this study restores visibility to women whose contributions have long been overlooked. The genetic evidence suggests that women played a crucial role in transmitting agricultural knowledge and shaping the evolutionary trajectory of entire populations. Through marriage and family life, they became agents of transformation.

Ancient DNA allows us to see this hidden influence. It gives voice to people who left no written records but whose biological legacy endures.

In the end, this is not just a story about genes. It is a story about resilience, adaptation, and human connection. It reminds us that history does not always move in sudden leaps. Sometimes, in the quiet corners of the world, it flows slowly like a river, shaped by the choices of ordinary people—especially women—whose impact echoes across thousands of years.

And thanks to the remarkable power of genomics, we can finally hear their story.

Study Details

David Reich, Lasting Lower Rhine–Meuse forager ancestry shaped Bell Beaker expansion, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-026-10111-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-026-10111-8