In the tropical lowlands of Mexico, where humid forests stretch toward the horizon and rivers carve their way to the Gulf, ancient giants lie in silence. They are not living beings but massive sculptures—faces hewn from stone, gazing with solemn dignity across the centuries. These are the Olmec colossal heads, among the most iconic and enigmatic creations of Mesoamerican civilization.

When one stands before them, there is an almost spiritual weight in the air. Towering up to three meters in height and weighing as much as 40 tons, these heads are not merely art—they are monuments of power, identity, and mystery. Their features are striking: broad noses, fleshy cheeks, thick lips, and helmets or headdresses that suggest authority or warfare. They are unlike anything else carved in the ancient world, distinct in both scale and symbolism.

But who made them, and why? To answer this, we must journey back more than 3,000 years to the dawn of civilization in the Americas, when the Olmec culture flourished in the swampy jungles of what is now Veracruz and Tabasco.

The World of the Olmec

The Olmec are often called the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica, for they were the first great civilization of the region, predating the Maya and Aztec by many centuries. Their world stretched from about 1500 BCE to 400 BCE, a time when monumental cities arose amidst the fertile floodplains of southern Mexico.

The Olmec heartland was a land of abundance but also challenge. Rivers such as the Coatzacoalcos provided fish, water transport, and rich alluvial soils for farming, but the environment was humid, swampy, and prone to flooding. Despite this, the Olmec thrived. They cultivated maize, beans, and squash; traded jade and obsidian; and developed complex spiritual systems.

Their cities—San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes—were centers of political, economic, and religious life. San Lorenzo, the earliest major site, rose to prominence around 1200 BCE and soon became a hub of monumental art. It was here, amid earthen mounds and ceremonial platforms, that the colossal heads first appeared.

The Making of Colossal Heads

The sheer scale of the colossal heads raises awe and questions in equal measure. Each head was carved from a single basalt boulder, quarried from the distant Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains. Some of these stones had to be transported over 60 miles across rivers and marshes, an extraordinary feat for a civilization without wheeled vehicles or draft animals.

Archaeologists believe the Olmec moved these boulders using rafts, rollers, and human labor, harnessing both ingenuity and sheer determination. Once at the carving site, artisans wielded stone tools—hammerstones and chisels—to gradually shape the basalt into human likeness. The work was painstaking, requiring not only physical strength but also extraordinary skill.

The heads vary in size but typically measure between 1.5 to 3 meters in height and weigh between 6 and 40 tons. The level of detail is remarkable, from the contours of the lips to the symmetry of the eyes. Each head is unique, suggesting that they are not generic representations but portraits.

Who Do the Heads Represent?

The prevailing interpretation is that the colossal heads represent rulers or elite figures of the Olmec society. Their individualized features, coupled with the helmets or headdresses, suggest they are not anonymous deities but powerful human beings immortalized in stone.

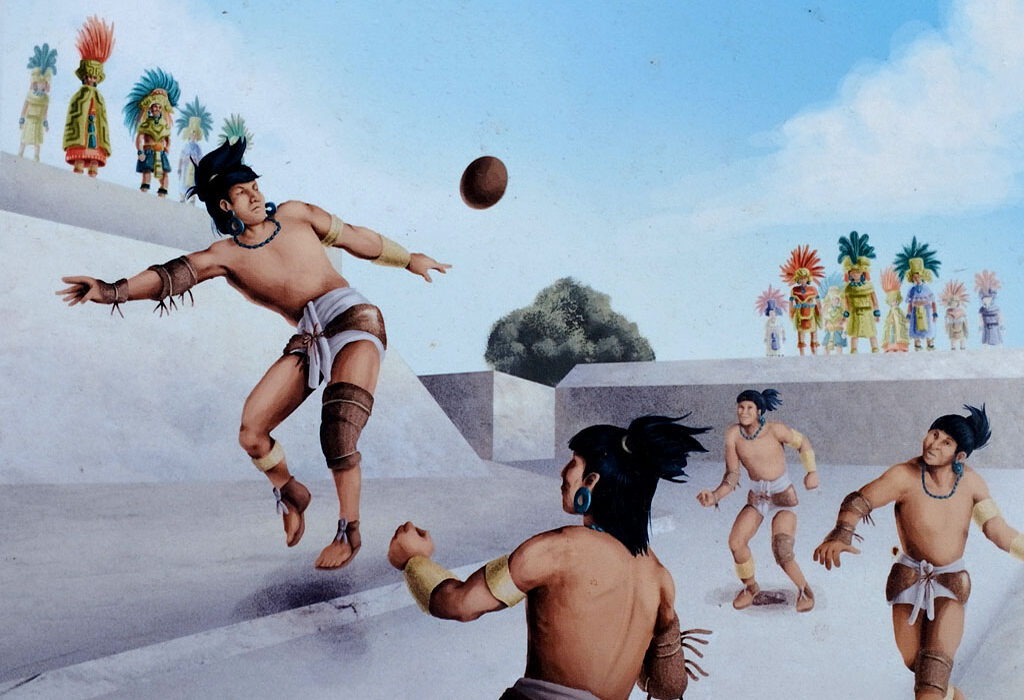

The helmets themselves are subject to debate. Some scholars suggest they represent protective gear worn in warfare. Others connect them to the sacred Mesoamerican ballgame, a ritualized sport with deep cosmological significance. In either case, the headdresses reinforce the association with power and status.

When one examines the colossal heads, there is a sense of personality in each one. Some seem stern, others contemplative, still others resolute. This individuality strengthens the theory that they are portraits, perhaps created to preserve the memory and authority of rulers long after their deaths.

Symbolism and Spiritual Power

In Olmec society, rulers were not just political leaders—they were intermediaries between the human and divine realms. Their authority was deeply entwined with religion, ritual, and cosmology. To immortalize a ruler in stone was not simply an act of commemoration but also a way to maintain their spiritual presence.

The colossal heads may have served as guardians of sacred spaces, positioned at plazas or ceremonial centers to watch over rituals. Their imposing size would have communicated power, both to the Olmec people and to visitors or rivals. In a world where authority was often justified by divine favor, these heads may have embodied the enduring might of sacred kingship.

Sites of the Colossal Heads

Seventeen colossal heads have been discovered to date, though some scholars suggest more may still lie buried beneath the jungles of Veracruz and Tabasco.

- San Lorenzo: The earliest and largest concentration of heads was found here. Ten heads have been unearthed, some buried or reused in later constructions, suggesting they had long-lasting significance.

- La Venta: Four colossal heads were discovered here, integrated into a ceremonial complex that also featured pyramids, plazas, and altars.

- Tres Zapotes: Two heads were found at this later Olmec site, dating toward the end of the civilization’s prominence.

- Rancho La Cobata: A single colossal head was found in this remote location, notable for being the largest of all, standing over 3 meters tall.

These discoveries illustrate that colossal heads were not isolated works but integral parts of Olmec ceremonial life, tied to centers of political and spiritual authority.

The Faces of Mystery

Despite centuries of study, the colossal heads remain enigmatic. Their expressions invite interpretation. Were they meant to intimidate, inspire, or immortalize? Their features are distinctive, leading some early scholars to speculate about influences from Africa or other distant lands. Such theories, however, lack archaeological evidence and are now largely rejected.

Instead, most scholars agree that the colossal heads are uniquely Olmec creations, reflecting the physiognomy of the local population and the cultural priorities of their society. The diversity of features among the heads underscores the individuality of rulers, not outside influence.

The Legacy of the Olmec

The Olmec civilization eventually declined around 400 BCE, but their influence echoed across Mesoamerica. Later cultures such as the Maya and Aztec inherited and transformed Olmec traditions—ritual ballgames, monumental architecture, sacred kingship, and religious iconography all bear Olmec roots.

The colossal heads, however, stand apart as singular achievements. They represent not only the artistry of a people but also their ability to organize massive labor forces, to mobilize resources, and to imbue stone with meaning.

Rediscovery and Modern Understanding

The colossal heads first entered modern awareness in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when explorers and archaeologists began documenting them. At first, their origins were puzzling, as the Olmec civilization itself had not yet been fully recognized. Some early theories attributed the heads to other Mesoamerican cultures, or even to faraway peoples.

It was not until the mid-20th century, through systematic excavations, radiocarbon dating, and contextual analysis, that scholars firmly established the Olmec as their creators. Today, the heads are celebrated as masterpieces of ancient art, recognized worldwide for their cultural and historical significance.

Preservation and Challenges

Preserving the colossal heads is no small task. Exposed to tropical humidity, erosion, and human activity, the stones are vulnerable. Some have been moved to museums for protection, while others remain in situ, where they continue to face environmental threats.

Local communities and the Mexican government work together to safeguard these treasures, recognizing their role not only as archaeological artifacts but as symbols of national heritage and identity.

What the Colossal Heads Teach Us

The colossal heads are more than stone sculptures—they are windows into the human experience. They teach us about leadership, memory, and the ways societies project power. They show us the ingenuity required to move mountains of basalt without wheels or metal tools. They remind us of the deep human desire to leave a mark, to be remembered long after death.

In the faces of the colossal heads, we glimpse the humanity of the Olmec—people who lived, ruled, dreamed, and created in a world very different from ours, yet connected by the same longing for meaning and legacy.

Conclusion: Giants in the Landscape of Time

Standing before an Olmec colossal head is to stand before history itself. These giants of stone have watched over jungles and rivers for millennia, silent witnesses to the rise and fall of civilizations. Their origins in the Olmec world remind us that humanity’s first experiments with complex society in Mesoamerica were as ambitious as any in Egypt, Mesopotamia, or China.

The colossal heads endure because they are more than relics—they are stories, identities, and presences carved into basalt. They challenge us to imagine the rulers they immortalize, the ceremonies they witnessed, and the people who poured their labor into shaping them.

In their immense silence, they speak across time: of power, of memory, and of the unyielding human drive to create monuments that outlast the fleeting span of life.