The moment a mammal is born, it steps into a world filled with microbes, foreign proteins, and environmental challenges. The infant’s immune system—newly awakened yet still inexperienced—must quickly learn to distinguish friend from foe. If it responds too strongly, it risks harming its own body through allergies or inflammation. If it responds too weakly, infections take hold. Striking the balance between defense and tolerance is not merely survival—it is the foundation of lifelong health.

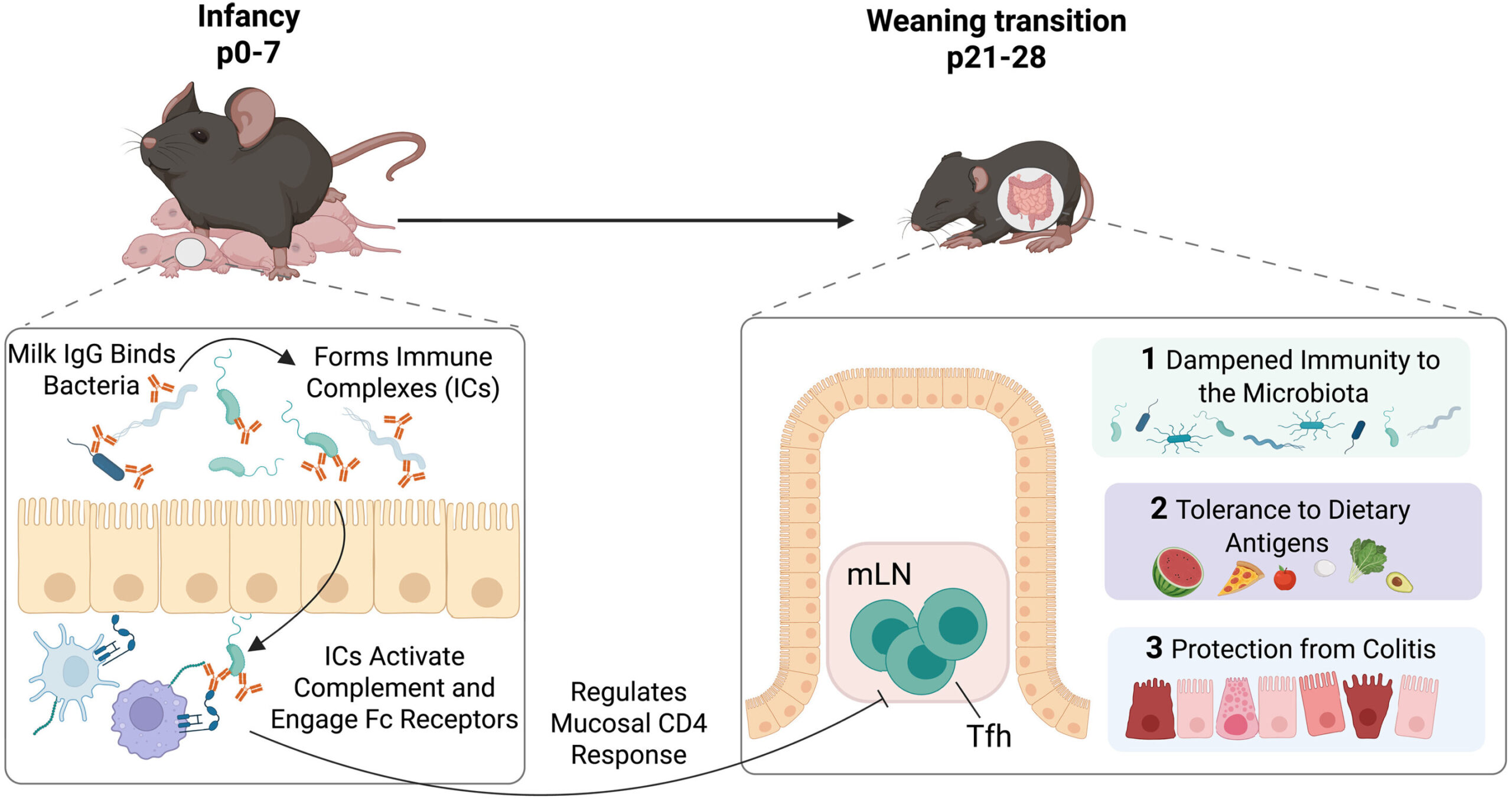

A new study from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, published in Science, reveals a surprising player in this delicate early-life education: maternal immunoglobulin G (IgG), an antibody present in breast milk. Long overshadowed by its cousin, IgA, IgG is now emerging as a quiet teacher in the neonatal gut—tuning the immune system in ways that may shape a lifetime.

The Hidden Lessons in Milk

Breast milk is often described as “liquid gold,” and for good reason. Beyond calories and hydration, it carries a remarkable collection of immune gifts: living microbes, complex sugars that feed beneficial bacteria, maternal cells, and antibodies. These elements do not simply nourish—they instruct, shaping the architecture of the infant gut and immune system.

For decades, scientists believed the star of this story was IgA. In adults, IgA coats mucosal surfaces and helps prevent microbes from invading tissues. But newborn physiology is different, and researchers began asking: what if another antibody plays a central role during those first fragile weeks of life?

Enter IgG. Abundant in milk, yet historically overlooked in neonatal research, IgG has now been shown to do more than simply guard against pathogens. According to this new work, it actively engages with the infant immune system, teaching it tolerance and balance.

Designing the Experiment

To uncover IgG’s role, researchers turned to mice, where the biology of milk and immune development is more easily studied. Some mouse pups were raised by mothers with antibodies, while others grew up antibody-deprived. To test timing, certain pups were cross-fostered immediately after birth, while others were introduced to antibody-rich milk days later. In another clever twist, purified IgG—collected from milk or blood—was fed directly to newborns in carefully measured doses.

The team controlled for nearly every variable: whether gut bacteria were present, which subclasses of IgG were most active, and which molecular “sensors” in the immune system were required for the effect. They even exposed pups to models of gut disease and food allergy, testing whether early antibody exposure made a difference later in life.

The results were striking.

The First Week Matters Most

The data revealed a critical “window of opportunity.” When newborn mice ingested maternal IgG during the first week of life, their immune systems developed with balance and restraint. Without this early antibody guidance, the story unfolded differently. After weaning, pups lacking early antibodies displayed overactive immune responses in their gut tissues. Their T follicular helper cells and B cells—powerful drivers of antibody production—became hyperactive, leading to exaggerated reactions against ordinary gut microbes.

The presence of gut bacteria was essential for these effects. Without microbes, the abnormal immune responses did not appear. In other words, maternal IgG seemed to mediate a conversation between the infant immune system and the microbial community arriving in the gut.

Perhaps most remarkable, feeding even small doses of purified IgG during the first week was enough to restore balance. The antibodies worked by binding directly to bacteria in the neonatal gut, particularly through the IgG2b and IgG3 subclasses. These antibody-microbe complexes activated the infant’s innate receptors and complement proteins, gently teaching the immune system to tolerate commensals rather than overreact.

More Than Protection—Instruction

Traditionally, antibodies are viewed as shields—molecules that neutralize pathogens and prevent infections. This study paints a more nuanced picture. In neonates, maternal IgG is not merely a protective guard but a teacher, shaping the immune system’s behavior.

By forming complexes with microbes, IgG teaches tolerance: the ability to live peacefully with commensals and dietary antigens. Mice that received maternal IgG were less prone to colitis, a condition marked by gut inflammation, and showed reduced allergic responses to dietary proteins. Those who missed this early guidance were more vulnerable to inflammatory and allergic disease.

The implication is profound. Breast milk does not simply lend the infant a temporary immune shield. It instructs the immune system how to function, setting the stage for resilience or vulnerability that may last a lifetime.

What About Humans?

Of course, mice are not humans. One important distinction is that mouse milk contains a proportionately higher amount of IgG than human milk. In people, IgA has long been recognized as the dominant antibody in breast milk. Still, the principle remains compelling: early antibody exposure, whether IgA, IgG, or both, likely plays a vital role in educating the infant immune system.

Human infants also receive IgG across the placenta before birth, stocking their immune toolbox for the first months of life. What remains less clear is how much the IgG in human breast milk contributes to long-term immune education. The new findings invite researchers to look more closely, perhaps uncovering hidden roles of IgG in shaping human health.

A Symphony of Early Life

This research adds to a growing recognition that early life is a symphony of signals—nutritional, microbial, and immunological—all converging to sculpt the infant’s future. The gut is not just a digestive organ in this context. It is a classroom, where microbes, antibodies, and cells engage in constant dialogue. Milk provides the textbook, filled with molecular lessons written by mothers over millions of years of evolution.

It also underscores why breastfeeding, when possible, is such a powerful tool for infant health. While formula provides calories and essential nutrients, breast milk delivers something more difficult to replicate: an orchestra of living, bioactive components that fine-tune the immune system.

The Broader Vision

The findings reach beyond the nursery. They may help us understand why some individuals develop allergies, autoimmune disorders, or inflammatory bowel disease, while others remain resilient. They suggest that supporting early-life immune education—whether through breastfeeding, antibody supplementation, or microbiome-targeted therapies—could reduce the burden of these diseases across populations.

They also remind us of a simple truth: in science, what seems ordinary is often extraordinary. A mother feeding her child is not just an act of nourishment but an act of molecular teaching, passing wisdom from one body to another in the form of antibodies and microbes.

Conclusion: The First Gift

So, what is maternal IgG? Not only a molecule of defense, but a first gift of instruction. It tells the newborn immune system: these microbes are friends, these foods are safe, this world is complex but navigable.

In the fragile dawn of life, before an infant can speak, before it can even open its eyes fully, a profound conversation takes place in the gut. It is a conversation between milk, microbes, and immunity. And thanks to science, we are just beginning to understand its depth, its poetry, and its promise for the future of health.

More information: Meera K. Shenoy et al, Breast milk IgG engages the mouse neonatal immune system to instruct responses to gut antigens, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.ado5294

Michael Silverman et al, Setting the table for immune tolerance, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adz8687