For years, researchers have been piecing together the puzzle of mental health in children and adolescents, but a new study may have just unlocked a critical piece. It’s the largest study of its kind, spanning five continents and including data from nearly 9,000 young people. What it reveals could change the way we think about mental health and treatment in youth forever.

The study, led by Dr. Sophie Townend from the University of Bath, takes an unprecedented look at the brains of children diagnosed with anxiety, depression, ADHD, and conduct disorder. It’s a detailed investigation into how these conditions might share underlying biological roots, specifically in brain structure. The results are not just scientifically groundbreaking—they are a glimpse into a future where mental health treatment could be more targeted, personalized, and effective for young people.

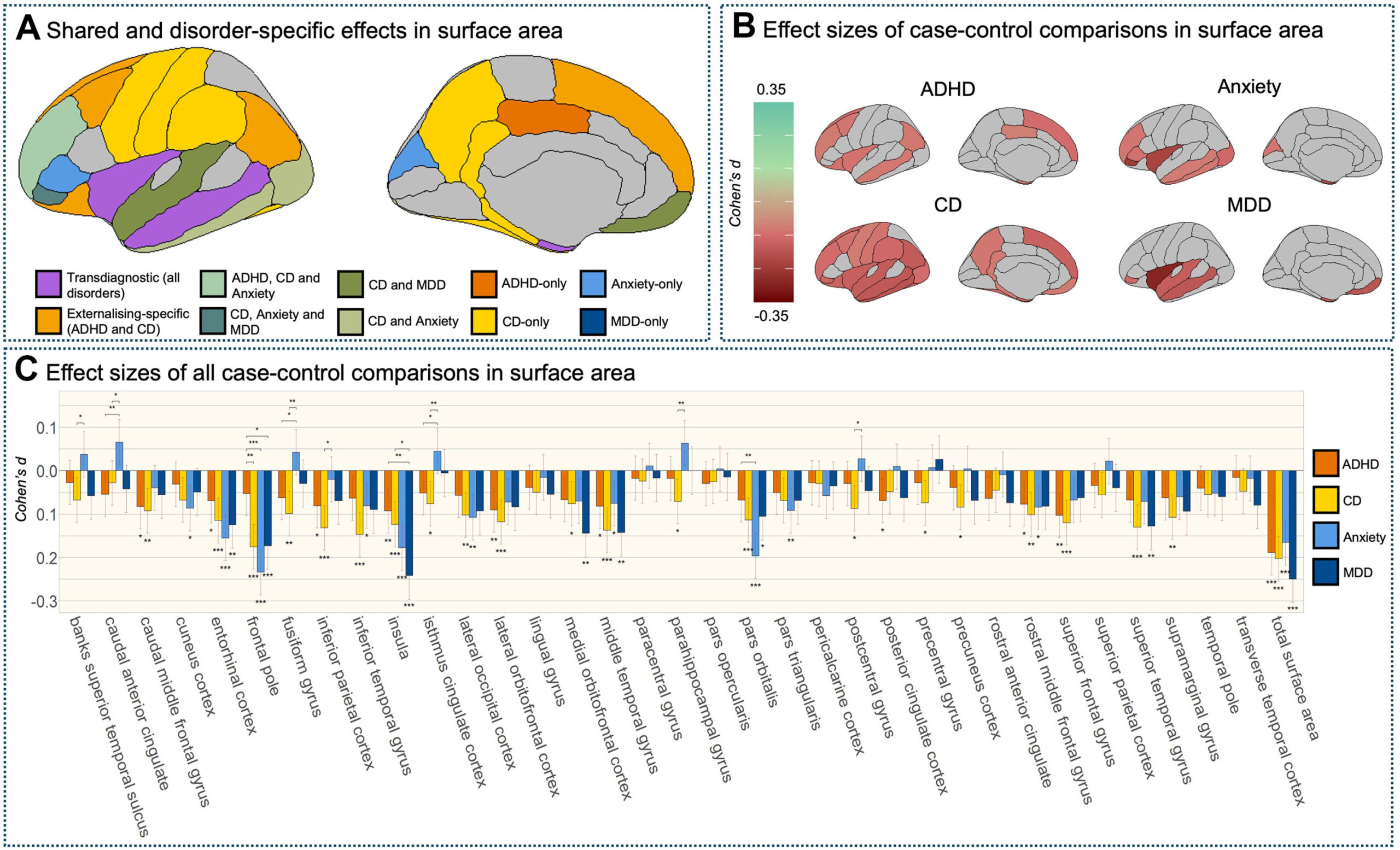

Dr. Townend and her team analyzed brain scans from nearly 4,500 children and adolescents with mental health conditions, comparing them to scans from those without diagnoses. What they uncovered were striking similarities—brain changes common to all four disorders, suggesting that despite the differences in symptoms and behaviors, these conditions may be more alike at the brain level than we ever realized.

The Shared Brain Changes that Tie These Disorders Together

At first glance, it might seem that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and conduct disorder are worlds apart. These conditions vary widely in how they present—some manifest as emotional distress, others as behavioral problems or difficulty with attention. But as Dr. Townend and her team dug deeper, they found a surprising commonality: all four disorders showed similar structural changes in the brain.

The key area of the brain impacted in all four disorders was the surface area of regions crucial for processing emotions, responding to threats, and maintaining awareness of bodily states. This is the part of the brain responsible for how we experience and react to the world around us. It turns out that these regions, which help manage emotions and bodily responses, are altered in similar ways across these different conditions.

“This suggests that there may be shared biological processes at play, even if the symptoms and behaviors of these disorders seem very different on the surface,” Dr. Townend explained. “Mental health disorders that start in childhood often go undiagnosed or untreated for many years—sometimes they are not recognized until adulthood. This places a major burden on individuals, families, and society, and causes a huge loss of human potential. For these reasons, it’s important that we try to understand these psychiatric disorders early in a person’s life.”

A Global Effort to Understand Youth Mental Health

What makes this study even more remarkable is the sheer scale and diversity of its data. Conducted by 68 research groups from all over the world, this study spanned continents and cultures, from North America to Europe, Asia, and beyond. The team’s findings challenge the conventional approach of studying these disorders in isolation. For years, mental health researchers have focused on specific disorders one at a time, treating them as distinct and separate. But this new research shows that there are more shared traits across these conditions than we may have realized.

By pooling data from such a vast range of sources, the research not only provides a more comprehensive understanding of youth mental health, but also hints at more effective ways to approach treatment. If these disorders share structural changes in the brain, could treatments that target those changes work for multiple conditions at once? The idea of tackling mental health disorders through a transdiagnostic approach—focusing on shared biological mechanisms rather than treating each condition separately—could revolutionize how we address mental health in young people.

“This study helps us understand the common neurobiological threads that run through different psychiatric disorders in children and young adults,” Dr. Townend said. “We now need to understand why the same brain changes might lead to disorders that seem very different to one another in terms of symptoms and behaviors.”

Surprising Findings About Gender Differences

Another unexpected finding from the study is how girls and boys with the same disorders showed similar changes in brain structure. Traditionally, research has shown that there are sex differences in the prevalence of these conditions. ADHD and conduct disorder are more commonly diagnosed in boys, while depression and anxiety tend to be more prevalent in girls. However, the new study revealed something surprising: when it comes to brain structure, the differences between girls and boys with the same diagnosis were far less pronounced than expected.

Professor Stephane De Brito, a collaborator from the University of Birmingham, noted, “While we know that there are sex differences in the prevalence of those disorders, our study shows that this doesn’t seem to translate into differences in brain structure.” This suggests that while environmental factors and societal pressures may help explain the gender disparities in who gets diagnosed, they are not reflected in the structural changes occurring in the brain. Instead, the brain’s alterations seem to be largely consistent across both genders, regardless of the disorder.

The implications of this discovery are significant. It suggests that, in terms of brain structure, boys and girls with these mental health conditions may be more alike than previously thought. But it also points to other factors—such as early life experiences or environmental influences—that could contribute to the gender differences we observe in the prevalence of mental health disorders.

Why This Research Matters

What does all of this mean for the future of mental health treatment in children and young adults? In short, it means that the way we think about mental health may need to change. Instead of seeing disorders like anxiety, depression, ADHD, and conduct disorder as distinct and unrelated, this research suggests that we should look for the common threads that connect them.

As Dr. Townend pointed out, the brain changes seen across these disorders are crucial to understanding how they develop and how they might be treated. If these conditions share similar alterations in brain structure, treatments that target those alterations could be more effective than current methods that treat each disorder separately. “Even if they may look very different, the four most common mental health conditions of childhood and adolescence are very similar at the brain level,” she said. “This suggests that we may be able to develop treatment or prevention strategies that are helpful for young people with a range of common disorders.”

This study also reinforces the importance of early diagnosis and intervention. The earlier we can identify the structural changes in the brain that underpin these disorders, the better equipped we will be to prevent or minimize the long-term effects of mental health conditions in children and adolescents. As Dr. Townend emphasized, the brain is still developing during childhood and adolescence, meaning that this is a crucial window for intervention. Getting it right at this stage could make a lasting impact on a young person’s life.

Ultimately, this research offers a new lens through which to view mental health. It challenges us to rethink traditional approaches and encourages a broader, more interconnected understanding of how these conditions emerge and how we can best support those affected by them. By focusing on shared biological mechanisms rather than isolated symptoms, we may be on the cusp of a new era in mental health care—one that could transform the way we approach childhood and adolescent mental health for years to come.

More information: Sophie Townend et al, Shared and Distinct Alterations in Brain Structure of Youth With Internalizing or Externalizing Disorders: Findings From the ENIGMA Antisocial Behavior, ADHD, Major Depressive Disorder, and Anxiety Working Groups, Biological Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2025.08.003