Deep in the heart of East Africa lies a region that has long been at the center of human origins research: the Omo-Turkana Basin. Spanning parts of Kenya and Ethiopia, this area is a treasure trove of ancient fossils, offering a glimpse into the distant past of early hominins—the ancestors of modern humans. For decades, scientists have uncovered vital clues to the story of human evolution here, but until now, the full picture has remained fragmented, like scattered pieces of a massive, ancient puzzle.

A new study, led by François Marchal, has just completed the painstaking work of stitching these pieces together. By integrating data from 117 research publications published over the past 55 years, the team has created a comprehensive catalog of hominin fossils from the region. Published in the Journal of Human Evolution, this study doesn’t just compile existing knowledge—it uncovers new patterns and insights about how early humans lived, evolved, and interacted with their environment.

The Hidden World of Fossils

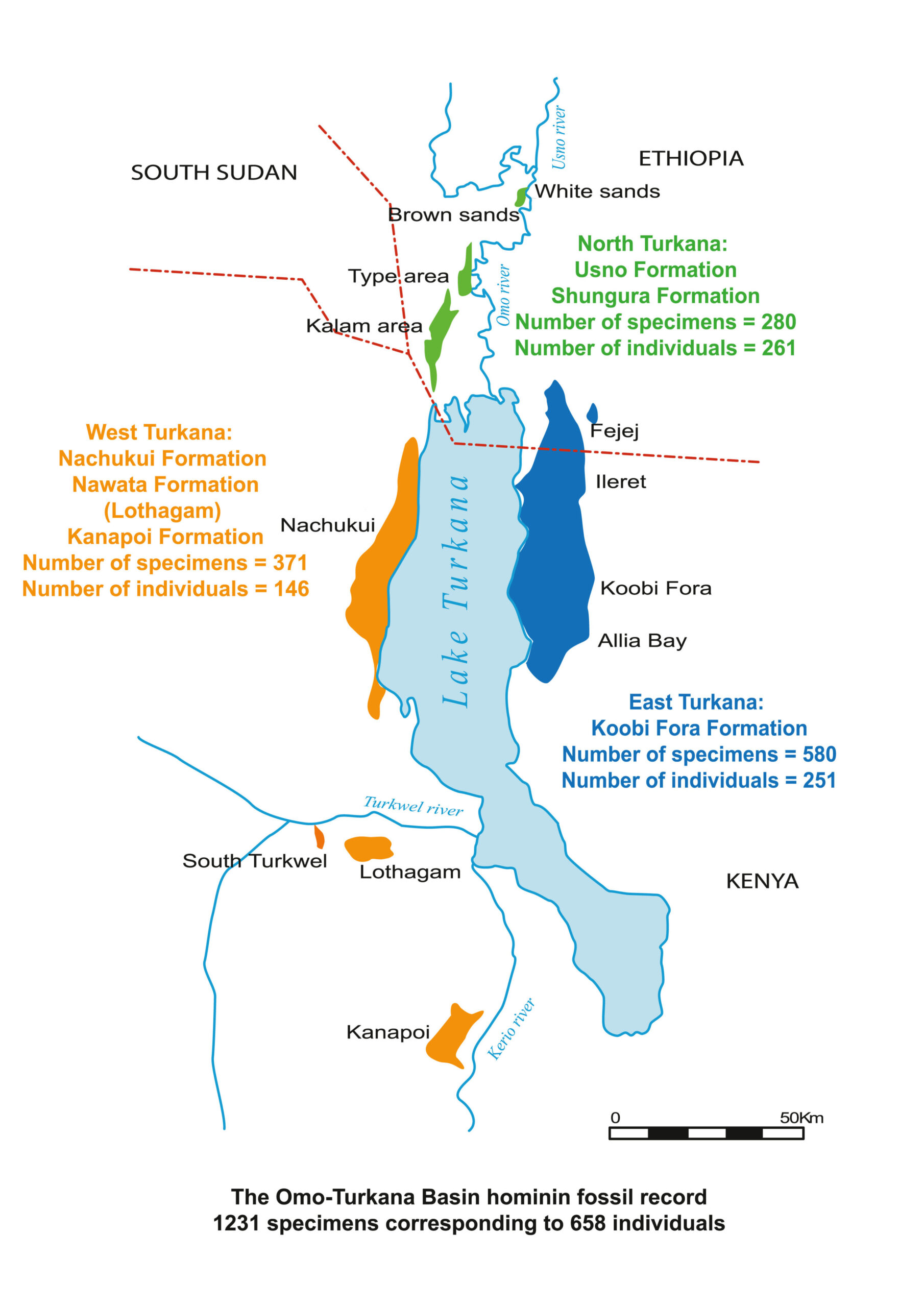

The Omo-Turkana Basin has long been one of the most important regions for studying human evolution. From 7 to 0.78 million years ago, it was home to a variety of hominin species, including the earliest members of our genus, Homo. Over the years, researchers have painstakingly gathered more than 1,200 hominin specimens from the region, representing at least 658 individuals. This extensive collection has provided invaluable information about the physical traits, behaviors, and environments of early humans.

However, until now, much of this information had been scattered across numerous studies and research teams. “The geographical position of the basin, spanning an international border, and its history of research by many different international teams have led to siloing of the data across the major parts of the basin,” the researchers explain. With so many different teams working independently in different regions, the fossil records were incomplete and fragmented. The data was there, but it hadn’t yet been woven together into a cohesive narrative.

By bringing together all the published fossil data, the research team was able to create a more integrated view of the region’s hominin history. This new approach revealed basin-wide patterns in how hominin fossils were distributed, how they were preserved, and how different species appeared and disappeared over time. With a clearer, more holistic view of the fossil record, the researchers were able to answer new questions about how early humans evolved.

The Uneven Fossil Record

One of the first surprises uncovered by the study was the uneven distribution of fossils across the basin. Fossils from the eastern section of the basin make up nearly half of all the specimens, while the western and northern sections contribute 30% and 23%, respectively. This uneven distribution reflects the different preservation conditions found in each area. Some regions were simply better suited for fossilization, while others offered more limited opportunities for remains to be preserved.

This unevenness is most apparent when examining the types of fossils that have been discovered. Teeth, for instance, make up the majority of the specimens—687 isolated teeth or tooth fragments were found. These hard, durable parts of the body are more likely to survive the ravages of time, offering a detailed look at the early hominins’ diet and health. Other skeletal remains, like cranial fragments, mandibles, and postcranial elements, are also plentiful but less complete. Only a handful of near-complete skeletons have been uncovered, which makes piecing together the full story of early hominin life a complex task.

Interestingly, the study found that the best-preserved fossils came from lakeshore environments in the eastern section of the basin, where conditions favored fossilization. Meanwhile, fossils from the northern, more river-like deposits were generally less complete, likely due to the harsher, less stable conditions for preservation.

The Evolutionary Tapestry of the Basin

This new study paints a vivid picture of the hominin species that lived in the Omo-Turkana Basin over the past 4 million years. The researchers found evidence of early hominins like Australopithecus anamensis, who roamed the region around 4 million years ago. Later, species like Kenyanthropus platyops appeared, marking important milestones in the evolution of early humans.

One of the most exciting revelations was the discovery of the extensive fossil record from the genus Homo. Between 2.7 and 2 million years ago, Homo rudolfensis, Homo ergaster, Homo habilis, and early Homo erectus all left their mark on the landscape. These species are crucial to our understanding of human evolution, as they represent the first members of our genus. The study found that at least 45 individuals from the genus Homo were represented in the fossil record from this period.

Perhaps even more fascinating was the finding that the genus Paranthropus coexisted with Homo for about 1.5 million years. Paranthropus, a robust, heavily built hominin, was actually more abundant than Homo in most areas of the basin. But in some regions, Homo was the dominant genus. This finding suggests a complex web of competition and co-existence among early hominins—a dynamic that has been crucial to understanding how our ancestors evolved.

The fossil record from the Omo-Turkana Basin also offers a rare look at nearly continuous hominin presence over a span of 2.7 million years. While there are some significant gaps in the fossil record—particularly between 2 and 1.5 million years ago—81% of the time interval between 4.2 and 1.5 million years ago is represented by fossils. This nearly uninterrupted fossil record gives researchers a unique opportunity to study how early hominins adapted to changing environments over long periods of time.

The Promise of New Discoveries

Though the team’s new study has brought to light important insights, it’s clear that the Omo-Turkana Basin still holds many secrets. Only 70% of the fossils have been assigned to a specific species, and many specimens remain under-described. But as the team notes, “new fossils will be unearthed, and previously discovered fossils will finally be described or better assigned taxonomically.” This ongoing research promises to bring even greater clarity to our understanding of human evolution.

Moreover, advancements in technology are making it easier for scientists to analyze fossils in unprecedented detail. New imaging techniques, along with methods for studying internal dental morphology and enamel thickness, are offering deeper insights into the biology and behavior of early hominins. Refined methods in geometric morphometry and analyses of discrete traits will help researchers more accurately assign fossils to specific species, refining our evolutionary tree.

The researchers also note that as fieldwork continues in the region, new fossils will undoubtedly be discovered, further expanding the fossil record and allowing for more precise dating of ancient events. This ongoing work will ultimately provide a clearer, more nuanced understanding of our evolutionary history.

Why This Matters

The research conducted in the Omo-Turkana Basin is more than just a catalog of ancient bones—it’s a key to understanding who we are and where we came from. By examining the fossils of early hominins, scientists are piecing together a story that connects us to our distant past. This research not only illuminates the biological evolution of our ancestors but also offers insight into the complex environmental and social dynamics that shaped early human life.

As more discoveries are made, this growing body of evidence will help us answer some of the most profound questions about human origins: How did early humans evolve? What challenges did they face? And how did they interact with their environment and other species? Each new fossil is a step closer to uncovering the answers—and understanding our place in the vast story of life on Earth.

More information: François Marchal et al, The hominin fossil record of the Omo-Turkana Basin, Journal of Human Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103731