For years, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, known more simply as CAR T-cell therapy, has stood as one of the most striking success stories in modern cancer medicine. In blood-based cancers, it has delivered outcomes once thought impossible, pushing some patients into deep remission. Yet solid tumors have remained stubbornly resistant, protected by their complexity and their ability to evade immune attack. A new laboratory study from Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center now suggests that this barrier may finally be weakening.

Led by Renier Brentjens, MD, Ph.D., a pioneer in CAR T-cell therapy and Deputy Director and Chair of the Department of Medicine at Roswell Park, the research outlines a new strategy that successfully eradicated solid tumors in preclinical models. By equipping CAR T cells with a powerful immune signaling molecule, the team uncovered a way to mobilize the body’s own immune system against cancers that have long resisted treatment.

Teaching Immune Cells to Speak a New Language

At the heart of this work is a simple but profound idea: CAR T cells do not have to fight alone. Traditionally, these engineered cells are designed to recognize specific proteins, called antigens, on cancer cells. Once they find their target, they attack directly. This approach has worked well in cancers where tumor cells consistently display a limited set of antigens, such as many blood cancers.

Solid tumors, however, are far more deceptive. They carry many different antigens on their surface, and they can change which ones they display. During treatment, they may simply stop producing the antigens that CAR T cells recognize, effectively hiding in plain sight. At the same time, the dense tissue surrounding solid tumors and the supportive environment known as the tumor microenvironment make it physically difficult for CAR T cells to reach their targets.

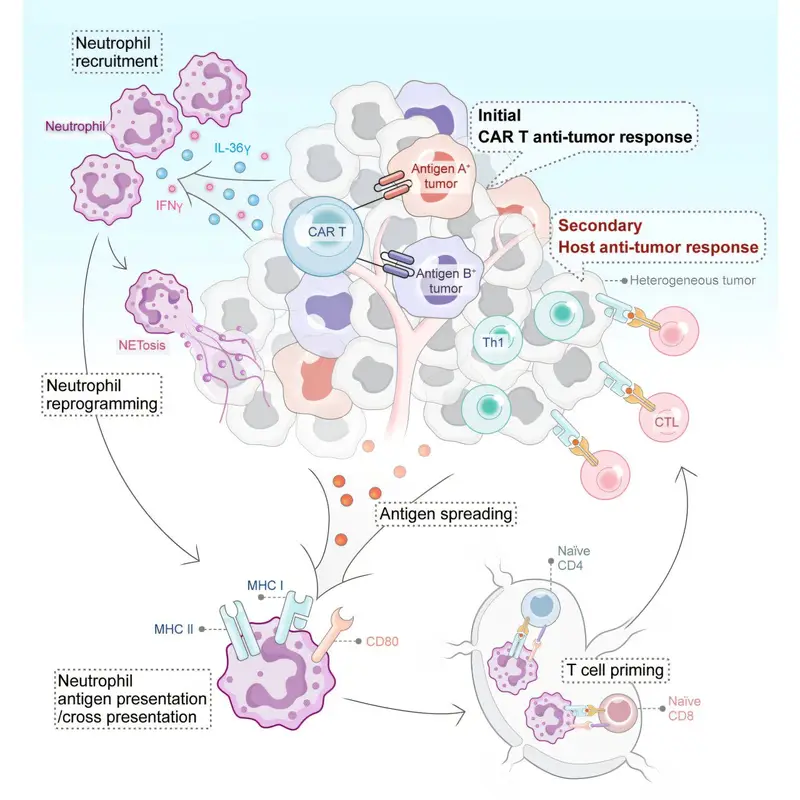

The Roswell Park team sought a way around these obstacles by enlisting help from other immune cells. They focused on Interleukin 36 gamma, or IL-36γ, a protein known to have wide-ranging effects on the immune system. By “armoring” CAR T cells with IL-36γ, the researchers hoped to spark a broader immune response inside the tumor itself.

Neutrophils Take on an Unexpected Role

The study, published in Cancer Cell, revealed something entirely unexpected. The IL-36γ–armored CAR T cells did not simply attack cancer cells directly. Instead, they reprogrammed neutrophils, a type of white blood cell traditionally associated with early, nonspecific immune responses, to become active participants in the anti-cancer fight.

Neutrophils are abundant and fast-acting, but they have often been overlooked in cancer immunotherapy. Recent studies have hinted that certain subsets of neutrophils can directly kill tumor cells and help shape longer-lasting immune responses. This new research goes further, showing that neutrophils can be coaxed into acquiring antigen-presenting functions, a role usually reserved for more specialized immune cells.

“What’s so exciting about this work is that it demonstrates a new mechanism by which CAR T cells can engage a patient’s own immune cells to go after solid-tumor malignancies,” says Dr. Brentjens, who holds The Katherine Anne Gioia Endowed Chair in Cancer Medicine at Roswell Park.

Rather than relying solely on engineered T cells to recognize and destroy cancer, the IL-36γ platform turns the tumor into a site of immune collaboration. Neutrophils, once recruited and reprogrammed, help activate a broader immune response that is no longer limited to a single antigen target.

A New Strategy Emerges in the Lab

Working with preclinical models of small cell lung cancer, the researchers tested CAR T cells designed to deliver IL-36γ directly within the tumor environment. The results were striking. The presence of IL-36γ triggered an innate immune response that amplified the attack on the tumor and ultimately led to its eradication in these models.

“Our study uncovers an unexpected level of immune collaboration activated by IL-36 gamma-armored CAR T cells,” says first author Yihan Zuo, Ph.D., a research scientist in Roswell Park’s Department of Medicine. “We were excited to find that neutrophils can be reprogrammed to acquire antigen-presenting functions and drive potent antitumor immunity. These insights open new possibilities for developing next-generation cell therapies for solid tumors.”

By activating both innate and adaptive arms of the immune system, the strategy sidesteps one of the greatest weaknesses of conventional CAR T-cell therapy in solid tumors. Even if cancer cells alter or lose specific antigens, the broader immune response can continue to recognize and attack them.

Rethinking a Standard Step in CAR T-Cell Therapy

The new approach also challenges another long-standing feature of CAR T-cell treatment. Standard protocols typically involve lymphodepletion, a preparatory step in which chemotherapy is used to eliminate the patient’s own lymphocytes. This clears space for the infused CAR T cells to expand and function.

In the IL-36γ strategy, lymphodepletion is skipped. Preserving neutrophils turns out to be essential, because these cells become key partners in the anti-tumor response. By sparing them, the armored CAR T cells can recruit and reprogram neutrophils rather than wiping them out before treatment even begins.

This shift highlights a deeper change in thinking about immunotherapy. Instead of viewing the patient’s existing immune cells as obstacles to be removed, the new model treats them as allies waiting to be activated.

A Breakthrough in a Persistent Puzzle

For researchers who have spent years grappling with the problem of solid tumors, the findings represent a significant conceptual advance. Scott Abrams, Ph.D., Jacobs Family Endowed Chair of Immunology at Roswell Park and co-senior author of the study, emphasizes the broader implications.

“The discovery of this unique CAR T cell/IL-36 gamma pairing defines a breakthrough not only in our basic understanding of the immune-tumor interaction but also a key advance in attacking solid cancers, which has remained a longstanding paradox,” he notes.

The paradox he refers to is the immune system’s apparent inability to eliminate solid tumors despite being capable of extraordinary feats elsewhere. This research suggests that the problem may not be a lack of immune power, but rather a lack of coordination.

Why This Research Matters

The promise of CAR T-cell therapy has always been tempered by its limitations. While transformative for certain blood cancers, its impact on solid tumors has remained frustratingly modest. The Roswell Park study offers a compelling new direction by showing that engineered T cells can be designed not just to kill, but to communicate.

By delivering IL-36γ directly into the tumor environment, CAR T cells become catalysts for a wider immune awakening. Neutrophils, once seen as blunt instruments, emerge as sophisticated players capable of shaping adaptive immunity and sustaining an anti-tumor response even as cancer cells try to hide.

“Our findings establish that the IL-36 gamma CAR T-cell platform holds promise as a possible treatment option for some advanced solid-tumor cancers for which there currently are no curative therapies,” says Dr. Brentjens.

Although the work remains at the laboratory stage, its implications are profound. It suggests that the future of cancer immunotherapy may lie not in ever more precise targeting of individual cancer markers, but in teaching the immune system to work together in new ways. For patients facing solid tumors that have long defied treatment, this collaborative immune strategy offers a renewed sense of possibility.

More information: Yihan Zuo et al, IL-36γ armored CAR T cells reprogram neutrophils to induce endogenous antitumor immunity, Cancer Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2025.11.007