Aging is inevitable. Our hair turns gray, our joints may creak, and the lines of experience etch themselves across our faces. Yet while aging cannot be stopped, the way we age can be profoundly shaped by the choices we make. Among these, exercise stands as one of the most powerful, natural, and universally accessible tools to maintain vitality and prevent age-related diseases.

Exercise is not merely a way to burn calories or shape muscles. It is a biological signal, a symphony of chemical and mechanical messages that tell our cells to repair, adapt, and thrive. Every step, every stretch, every beat of the heart during activity translates into a protective shield against the ravages of time. Exercise does not just add years to life—it adds life to years.

Aging and the Body: The Slow Drift

Before we understand how exercise protects us, it is important to recognize what happens when the body ages. Over time, muscles weaken, bones lose density, arteries stiffen, and metabolism slows. These natural changes increase the risk of chronic illnesses such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and certain cancers.

The immune system, once robust, becomes sluggish, leaving us more vulnerable to infections. Cognitive decline begins to appear, with memory lapses and slower processing speeds. Even the body’s ability to repair DNA and fight off cellular damage declines, allowing oxidative stress and inflammation to accumulate.

This slow drift is not uniform. Some people remain vibrant into their nineties, while others develop debilitating conditions in midlife. Lifestyle plays a decisive role here—and exercise, in particular, emerges as one of the most powerful determinants of healthy aging.

Exercise as Medicine

Modern science increasingly views exercise as a form of medicine. Unlike pharmaceuticals, it comes without a prescription, costs nothing, and delivers benefits to nearly every system in the body simultaneously. The World Health Organization recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, but even smaller amounts of physical activity have measurable health benefits.

Exercise works through multiple mechanisms. It improves circulation, reduces inflammation, enhances insulin sensitivity, strengthens muscles and bones, and sharpens the mind. Unlike a pill that targets one pathway, exercise activates a cascade of protective effects throughout the body.

Protecting the Heart: Exercise and Cardiovascular Health

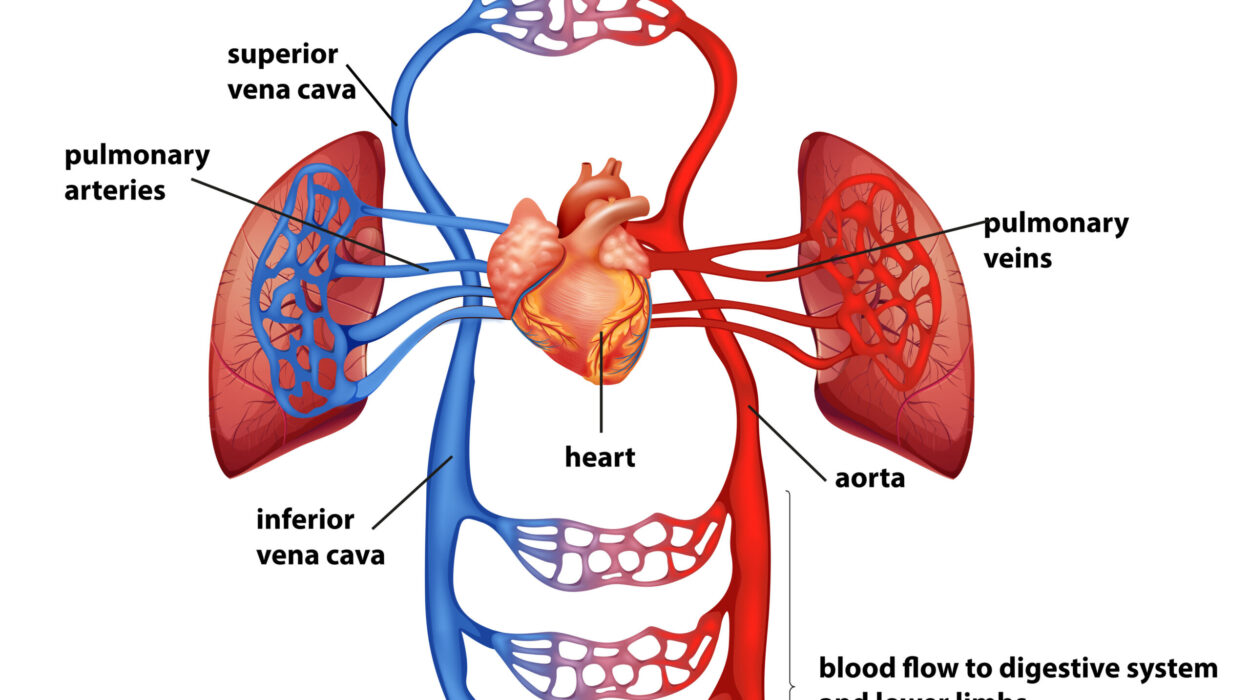

One of the most significant threats of aging is cardiovascular disease. The stiffening of arteries, accumulation of plaque, and weakening of the heart muscle increase risks of heart attack, stroke, and hypertension. Exercise directly counters these processes.

Aerobic activities such as walking, cycling, and swimming improve the elasticity of blood vessels, reducing blood pressure and enhancing circulation. Regular movement lowers LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) while raising HDL cholesterol (the “good” cholesterol). It also reduces systemic inflammation, which is increasingly recognized as a key driver of atherosclerosis.

Studies show that older adults who engage in regular physical activity have up to a 35% lower risk of cardiovascular disease. Even light activities, like gardening or brisk walking, reduce risks compared to sedentary lifestyles. In essence, every heartbeat elevated by exercise is an investment in a healthier, more resilient cardiovascular system.

The Muscle Fountain of Youth

Muscle loss, or sarcopenia, is one of the most visible and disabling effects of aging. By the time many people reach their seventies, they may have lost 25–50% of their muscle mass. This decline not only reduces strength but also increases the risk of falls, fractures, and loss of independence.

Resistance training—lifting weights, using resistance bands, or even bodyweight exercises—acts as a fountain of youth for muscles. It stimulates muscle fibers to grow and adapt, even in advanced age. Research has shown that individuals in their nineties can still build muscle strength with regular resistance training.

Exercise also preserves motor neurons, the nerve cells that control muscle contractions. This neuromuscular preservation translates into better balance, coordination, and agility—qualities that make the difference between remaining active or being confined to immobility.

Bones and Joints: Guarding Against Osteoporosis and Arthritis

As we age, bones naturally lose density, and joints undergo wear and tear. Osteoporosis, characterized by brittle bones, and arthritis, marked by joint inflammation, are common age-related conditions that rob people of independence and quality of life.

Weight-bearing exercises such as walking, jogging, and strength training stimulate bone remodeling, encouraging bones to retain calcium and strengthen their structure. Exercise also increases flexibility and lubrication in joints, reducing stiffness and improving range of motion.

While exercise cannot reverse arthritis, it reduces pain by strengthening surrounding muscles, decreasing joint stress, and improving circulation to cartilage. In this way, movement itself becomes therapy.

Exercise and the Brain: Protecting Memory and Cognition

Perhaps one of the most feared aspects of aging is cognitive decline—losing memory, reasoning, and independence. Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia affect millions worldwide, and while no cure exists, exercise offers powerful prevention.

Aerobic exercise increases blood flow to the brain, delivering oxygen and nutrients essential for neuronal health. It stimulates the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), often called “fertilizer for the brain,” which supports the growth of new neurons and strengthens synaptic connections.

Regular physical activity is linked to larger hippocampal volume—the part of the brain responsible for memory and learning—even in older adults. Moreover, exercise reduces the risk of vascular dementia by improving blood vessel health and preventing small strokes.

Cognitively, physically active older adults demonstrate better attention, faster processing speed, and greater resilience to stress. The act of movement itself, especially activities requiring coordination like dancing or tai chi, combines physical and cognitive stimulation, reinforcing neural pathways.

Diabetes and Metabolic Health

Type 2 diabetes is a classic age-related disease, driven by insulin resistance and metabolic slowdown. Exercise directly combats these mechanisms. When muscles contract, they absorb glucose from the blood independently of insulin, lowering blood sugar levels. Over time, regular activity improves insulin sensitivity, reducing the risk of developing diabetes.

Even short bouts of movement after meals, such as a 10-minute walk, significantly reduce blood sugar spikes in older adults. Combined with dietary care, exercise has the power not only to prevent diabetes but to manage and sometimes reverse it.

The Immune System: Defending Against Infection and Inflammation

The immune system naturally declines with age, a process known as immunosenescence. This makes older adults more susceptible to infections, slower to heal, and more vulnerable to chronic inflammation—a silent contributor to heart disease, diabetes, and even cancer.

Exercise enhances immune surveillance. Moderate physical activity increases the circulation of immune cells, helping the body detect and neutralize pathogens more effectively. It also reduces chronic inflammation by lowering stress hormones and stimulating anti-inflammatory cytokines.

While excessive, intense exercise without rest can suppress immunity, moderate regular activity strengthens the immune system and reduces age-related vulnerabilities.

Cancer Prevention and Exercise

Although cancer is influenced by genetics and environmental factors, lifestyle plays a major role in its risk. Exercise lowers the likelihood of several cancers, including breast, colon, and prostate cancers. It does so by regulating hormone levels, improving immune defense, and reducing obesity-related inflammation.

For cancer survivors, exercise improves recovery, lowers recurrence risk, and enhances quality of life. It reduces fatigue, boosts mood, and restores physical function—reminding us that exercise is as much about living well as it is about preventing illness.

Mental Health and Emotional Resilience

Aging often brings psychological challenges: loss of loved ones, retirement, or chronic conditions that threaten independence. Depression and anxiety are common but often overlooked in older adults. Exercise acts as a natural antidepressant and anxiolytic.

Physical activity triggers the release of endorphins and serotonin, neurotransmitters that elevate mood and reduce stress. Group exercise classes or walking clubs add social interaction, counteracting loneliness—a significant risk factor for poor mental health in older populations.

By supporting both brain chemistry and social connection, exercise becomes a pillar of emotional resilience in aging.

Longevity and Quality of Life

The ultimate promise of exercise is not just longer life but better life. Studies consistently show that physically active individuals live longer than their sedentary peers. But more importantly, their later years are characterized by greater independence, mobility, and joy.

This distinction—between lifespan and healthspan—is crucial. It is not enough to add years to life if those years are marked by disability and suffering. Exercise extends healthspan, ensuring that the extra years are lived with dignity and vitality.

Exercise Across the Lifespan: Building for the Future

The benefits of exercise are cumulative. The earlier in life one develops the habit of regular activity, the greater the protection against age-related diseases. Yet, it is never too late to start.

Studies show that individuals who begin exercising in their sixties or seventies still gain significant improvements in cardiovascular health, muscle strength, and cognitive function. Even small changes—such as daily walks or gentle stretching—initiate positive adaptations.

Movement is ageless, and its benefits are universal.

Overcoming Barriers to Exercise in Aging

Despite its clear benefits, many older adults face barriers to exercise: pain, fear of injury, lack of motivation, or limited access to facilities. These barriers are real, but they are not insurmountable.

Low-impact activities like swimming, tai chi, or chair exercises provide safe alternatives. Gentle strength training with resistance bands can be done at home. Community programs, walking groups, and physical therapy sessions create supportive environments.

The key is to focus on enjoyment and consistency rather than perfection. Exercise should feel like a celebration of movement, not a punishment for aging.

The Science of “Use It or Lose It”

The principle of “use it or lose it” defines the role of exercise in aging. Muscles not used atrophy, bones not stressed weaken, and minds not stimulated dull. Movement is the language through which the body expresses vitality.

When we move, we tell our bodies to stay alive, to stay strong, to stay connected. Each heartbeat elevated, each muscle engaged, each breath deepened is a declaration against decline.

Conclusion: A Path Toward Healthy Aging

The role of exercise in preventing age-related diseases is not a matter of debate—it is a matter of evidence, lived experience, and timeless wisdom. Science confirms what human tradition has long known: the body was made to move, and through movement, it thrives.

Exercise preserves the heart, strengthens bones, protects the brain, balances metabolism, enhances immunity, and uplifts the spirit. It transforms aging from a story of inevitable decline into a story of resilience, independence, and joy.

Aging will always change us, but with exercise, we can choose how it changes us. We can choose vitality over fragility, strength over weakness, clarity over confusion, and joy over despair. Exercise is not just a habit—it is a lifelong companion, walking with us through the seasons of life, ensuring that we do not merely survive into old age but truly live.