As twilight deepens and cities ignite into shimmering constellations of artificial light, we feel more connected, more awake, more alive. But a groundbreaking new study suggests that this night-time brilliance—so essential to our modern world—might be subtly darkening something else: our mental health.

In a paper published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists have uncovered a direct biological pathway linking exposure to artificial light at night (LAN) with depression-like behavior in mammals. The study, led by a consortium of Chinese research institutions, not only pinpoints a neural circuit that mediates this effect but also sounds a quiet warning for a society increasingly flooded with nocturnal illumination.

The research focused on tree shrews—small, squirrel-like mammals that, like humans, are active during the day and rest at night. Their biological similarities to primates make them an ideal subject for probing the effects of LAN on diurnal creatures. What researchers found could have sweeping implications for urban populations bathed in the cold glow of streetlamps, office lights, and phone screens.

When the Night Isn’t Dark Enough

For three weeks, the team led by Prof. Xue Tian of the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), Prof. Yao Yonggang of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, and Prof. Zhao Huan of Hefei University exposed the tree shrews to two hours of blue light each night—roughly the same color temperature as your phone screen or a brightly lit room.

That limited exposure was enough to transform the animals’ behavior. The tree shrews showed clear signs of what in humans would be diagnosed as depression: they lost interest in sugar water, a marker of anhedonia—the inability to feel pleasure. Their curiosity diminished, and they struggled with long-term memory tasks. The once lively, inquisitive animals had become subdued and withdrawn.

This wasn’t a case of disturbed sleep or circadian rhythm disruption alone—it was something deeper, and the scientists wanted to know why.

The Light-to-Mood Highway

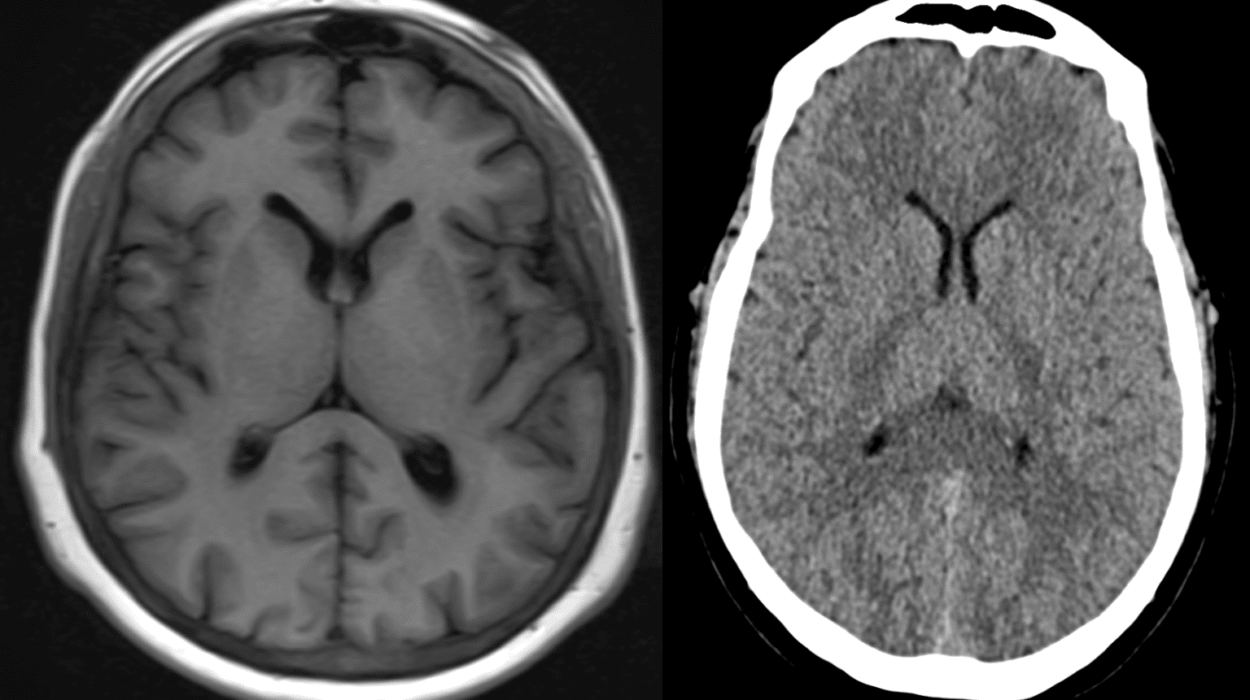

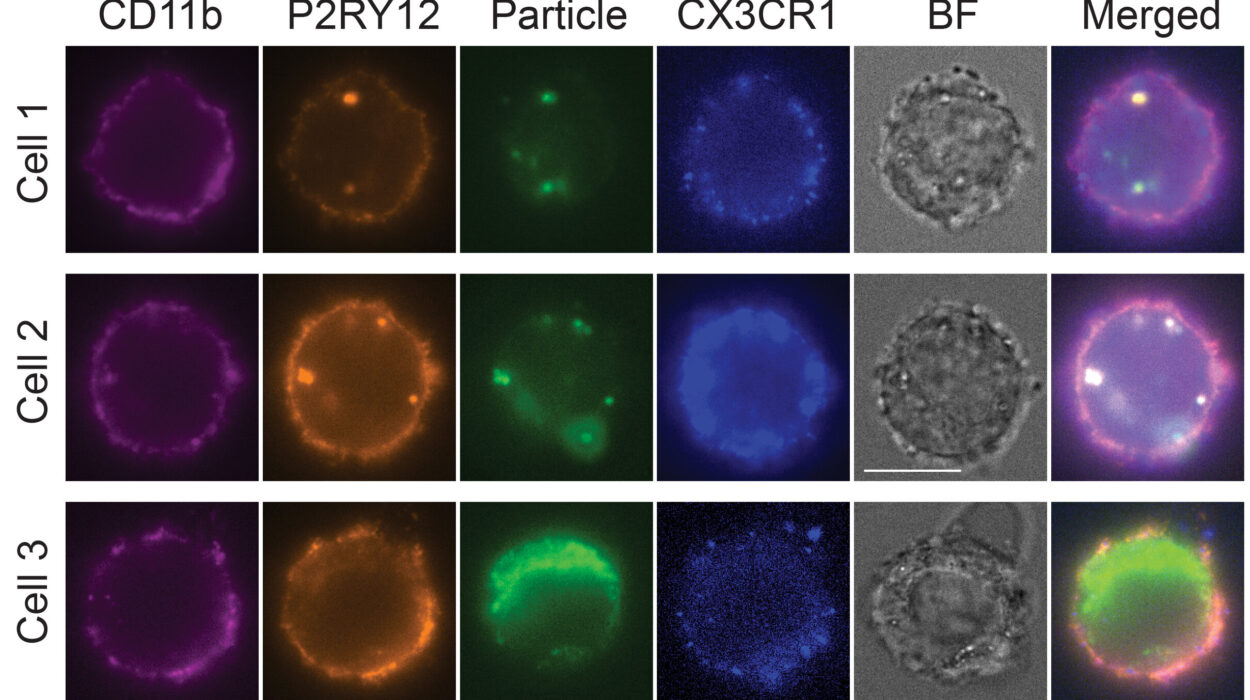

Using cutting-edge neural tracing techniques, the researchers mapped out a visual pathway never before documented. The discovery centered on a class of specialized retinal ganglion cells—photoreceptors distinct from those that give us vision. These cells were found to send light signals directly to a small brain structure known as the perihabenular nucleus (pHb), nestled deep in the thalamus.

From the pHb, signals flowed to the nucleus accumbens, a brain region that plays a central role in motivation, reward, and emotional regulation. This neural “light-to-mood” circuit effectively bypassed traditional visual pathways, offering a direct route for nighttime illumination to influence emotional states.

When scientists chemically silenced the pHb neurons, the result was striking: even under the same nightly light exposure, the animals no longer developed depression-like behaviors. It was as though the mood-altering effects of artificial light had been turned off at the switch.

Further RNA sequencing revealed that LAN exposure altered expression patterns in key genes related to depression—offering a molecular fingerprint for the psychological toll of light pollution.

A Wake-Up Call in a World That Never Sleeps

“This study gives us both a warning and a roadmap,” said Prof. Yao Yonggang. “The same light that enables our nighttime productivity may be subtly reshaping brain circuits underlying mood—but now we know where to look for solutions.”

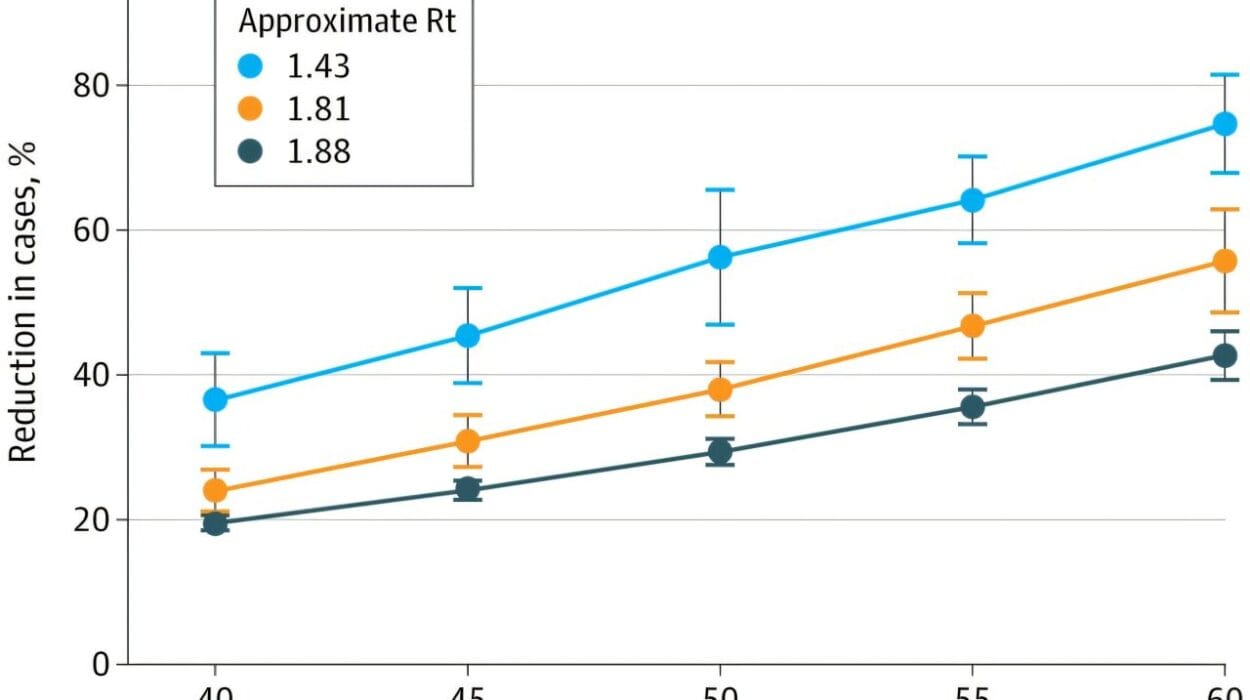

The implications are profound. Modern life is increasingly illuminated: satellite images show the Earth’s surface glowing ever more brightly year after year. Blue-rich light from screens, LEDs, and even streetlamps is a common feature of urban nightscapes. For millions, true darkness is a rare luxury.

Yet while our societies thrive on 24/7 connectivity and illuminated streetscapes, our biology may be struggling to keep pace. Mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety are on the rise globally, especially in urban environments. This study raises a disquieting possibility—that artificial light could be one of the invisible contributors.

Of course, tree shrews are not humans. But the fact that these mammals share similar diurnal rhythms and brain architecture with us makes the findings impossible to dismiss.

The Hidden Cost of the Glow

The research doesn’t suggest we return to candlelight or shun our screens completely. Instead, it urges a more nuanced understanding of how artificial light shapes our internal world.

In recent years, sleep scientists have warned of the dangers of late-night screen use and light pollution’s effects on circadian rhythms. But this study shifts the conversation: it suggests that LAN isn’t just messing with sleep—it may be directly interfering with mood regulation in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

One of the most important takeaways is the identification of a specific neural pathway. This gives researchers and clinicians a new target for potential interventions—whether through lighting design, pharmaceuticals, or behavioral therapies.

“If we can find ways to limit activation of this circuit or counteract its effects,” said Prof. Tian, “we might be able to protect mental health without compromising the benefits of artificial light.”

Light, Mood, and the Future

The study’s findings also open the door to deeper philosophical and societal questions: how much light is too much? How can we design cities, homes, and technologies that respect our biological limits? Could the modern epidemic of loneliness, stress, and anxiety be traced, in part, to a world that never dims?

From urban planning to mental health care, the answers could ripple outward.

In the meantime, experts suggest simple strategies may help mitigate LAN’s effects: use warmer, dimmer light in the evenings. Limit screen time before bed. Consider blackout curtains or eye masks in bright urban areas. And perhaps most importantly, don’t underestimate the power of darkness. Our brains may need it more than we think.

As artificial light continues to stretch the day into night, this study reminds us that nature evolved in rhythm with the sun and stars. And even in our most modern moments, those rhythms still pulse in our neurons, shaping how we feel, think, and thrive.

Reference: Ying Miao et al, Light at night negatively affects mood in diurnal primate-like tree shrews via a visual pathway related to the perihabenular nucleus, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2411280122