Motivation is the invisible force that propels us from the quiet inertia of comfort into the storm of action. It is the spark that ignites our passions, the silent engine that fuels creativity, ambition, and resilience. Yet, motivation is also fragile—fluctuating, elusive, and sometimes maddeningly inconsistent. Why do some days burst with boundless energy while others feel like an uphill battle? The answers lie deep within the folds of the brain, where biology, psychology, and experience converge in a delicate dance.

Neuroscience—the study of the nervous system—has begun to unravel the complex mechanisms that generate motivation. This journey takes us into the heart of brain circuits, neurotransmitters, hormones, and the interplay between reward and effort. Understanding these processes not only satisfies intellectual curiosity but also equips us to harness motivation more effectively in daily life.

Motivation as a Biological Imperative

At its core, motivation is rooted in survival. From the simplest organisms to humans, motivation serves to promote behaviors that sustain life: seeking food, shelter, reproduction, and social connection. The brain has evolved sophisticated systems to reward behaviors that increase chances of survival and reproduction, creating a feedback loop that shapes habits, desires, and goals.

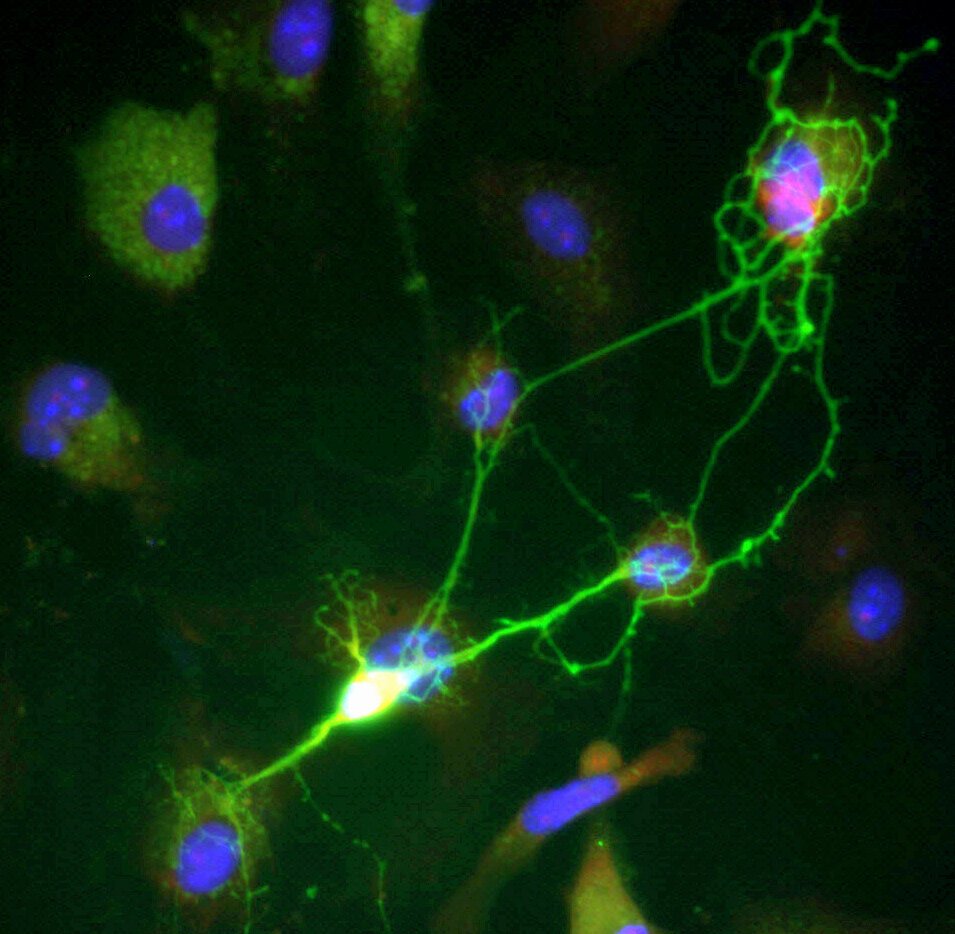

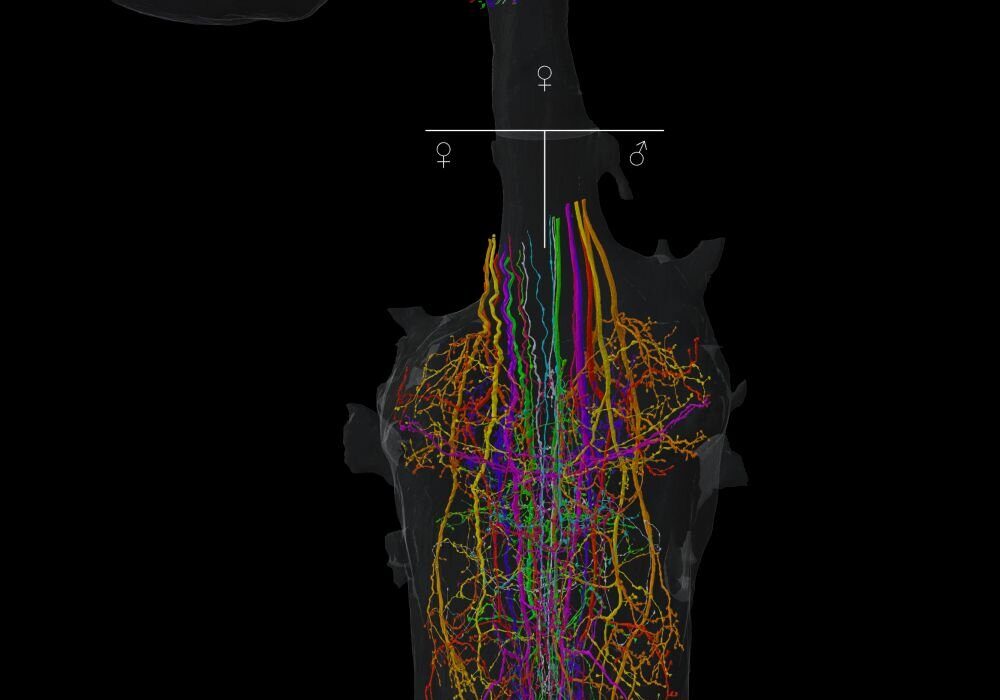

Within the brain, the mesolimbic dopamine system stands as a central player. Often described as the brain’s reward pathway, this system connects the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the midbrain with the nucleus accumbens, a region in the forebrain critical for experiencing pleasure. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter, is released in this circuit when we encounter something rewarding—whether it’s food, social approval, or an anticipated success.

Yet, dopamine’s role is not simply to make us feel good. Research shows it acts more like a “motivational salience” signal, tagging stimuli that are worthy of attention and effort. It pushes us to seek, to anticipate, to strive. Without dopamine, even the most enticing goals become dull and uninspiring.

The Dual Nature of Motivation: Wanting vs. Liking

Motivation is often mistaken as a singular sensation, but neuroscience reveals it has at least two intertwined components: wanting and liking. “Wanting” is the drive to obtain a reward; “liking” is the pleasure derived from consuming or experiencing it.

The fascinating—and sometimes frustrating—truth is that these two can diverge. For example, addictive substances can increase “wanting” (craving) without a corresponding increase in “liking” (pleasure). This dissociation explains why people continue harmful behaviors despite diminishing satisfaction.

In everyday life, the wanting system is critical to goal pursuit. When motivation wanes, it often reflects a deficit in this drive to act, not necessarily a lack of pleasure in the goal itself. Understanding this distinction can help frame strategies for sustaining motivation, focusing on reigniting desire rather than merely seeking pleasure.

The Prefrontal Cortex: The Brain’s Executive Motivator

While the dopamine system sets the stage for motivation, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) provides the direction and control. The PFC is the brain’s command center for planning, decision-making, and self-regulation. It evaluates the value of potential rewards, weighs risks, and inhibits distractions.

Motivation without prefrontal oversight is aimless; the PFC channels raw drive into purposeful action. It helps transform abstract desires into concrete goals and sustainable habits. Its activity correlates strongly with persistence and the ability to delay gratification, essential for long-term success.

Damage or dysfunction in this region can lead to apathy or impulsivity, illustrating its critical role. Furthermore, the PFC is highly plastic, meaning motivation can be strengthened through practice, habit formation, and even mindfulness techniques that enhance executive control.

Emotional and Social Dimensions of Motivation

Motivation is not purely a cold calculation of rewards and costs. Emotions infuse motivation with urgency, meaning, and personal relevance. The amygdala, a small almond-shaped structure, processes emotional salience and signals to the PFC and reward systems when something is important or threatening.

Social factors amplify this process. Humans are inherently social beings, and social approval, connection, and status are powerful motivators. The release of oxytocin, often called the “bonding hormone,” during social interactions further modulates motivation by enhancing trust and cooperation.

Moreover, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) monitors conflicts and errors, signaling when effort should be increased or when a goal is worth persevering for despite setbacks. This brain area links motivation closely with resilience, the emotional stamina to endure challenges.

The Role of Stress and Fatigue in Motivation

Not all motivation is positive. Chronic stress, fatigue, and emotional exhaustion can hijack the brain’s motivational circuits. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis governs the body’s response to stress by releasing cortisol. While acute stress can boost motivation and alertness, chronic stress floods the system, impairing dopamine function and PFC activity.

Fatigue also dulls motivation by depleting the brain’s energy reserves and disrupting neurotransmitter balance. Sleep deprivation, for example, reduces dopamine receptor sensitivity, leading to diminished reward responsiveness. This biological toll can create a vicious cycle where low motivation worsens performance and well-being, further lowering motivation.

Understanding these interactions emphasizes the importance of self-care—adequate sleep, stress management, and nutrition—in sustaining motivation.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Neuroscientific Divide

Psychologists differentiate between intrinsic motivation—engaging in an activity for its inherent satisfaction—and extrinsic motivation—driven by external rewards or pressures. Neuroscience offers insights into how these forms manifest in the brain.

Intrinsic motivation activates brain regions associated with self-referential processing and curiosity, such as the medial prefrontal cortex and the ventral striatum. It is linked to dopamine release in a way that feels more fulfilling and sustainable.

Extrinsic motivation, while effective in certain contexts, may rely more heavily on external dopamine surges and can sometimes undermine intrinsic motivation if rewards feel controlling or excessive. This phenomenon, known as the “overjustification effect,” demonstrates how external rewards can diminish internal drive.

Balancing these motivational types is key to fostering long-lasting inspiration.

The Neurochemistry of Motivation Beyond Dopamine

Although dopamine is the star player, other neurotransmitters and hormones contribute to the intricate tapestry of motivation. Serotonin, often associated with mood regulation, influences patience and impulse control. Higher serotonin levels are linked to increased tolerance for delayed rewards, facilitating sustained effort.

Norepinephrine, part of the brain’s arousal system, enhances focus and alertness, priming the brain to respond to motivational cues. Meanwhile, endorphins and oxytocin play roles in social bonding and stress relief, which indirectly support motivation by creating a positive emotional state.

Understanding this neurochemical symphony reveals why motivation is not a single switch but a complex, dynamic state influenced by multiple internal factors.

Motivation and the Brain’s Prediction Engine

Recent neuroscience research suggests that the brain operates fundamentally as a prediction machine. It continuously generates expectations about rewards and outcomes and adjusts motivation based on prediction errors—differences between expected and actual results.

When outcomes exceed expectations, dopamine neurons fire more intensely, reinforcing behaviors and boosting motivation. Conversely, when outcomes fall short, dopamine firing decreases, leading to demotivation or the search for new strategies.

This framework explains why novelty and challenge often enhance motivation, as unexpected success creates powerful positive prediction errors. It also accounts for the frustration and loss of drive that follow repeated failure.

Cultivating Motivation: Practical Insights from Neuroscience

The scientific understanding of motivation offers concrete ways to nurture and sustain inspiration. First, setting clear, attainable goals engages the PFC and dopamine system, providing direction and frequent reward signals. Breaking large ambitions into manageable steps allows for steady dopamine release, reinforcing progress.

Second, embracing intrinsic motivation by connecting activities to personal values and curiosity stimulates the brain’s natural reward pathways more effectively than external incentives alone.

Third, managing stress and prioritizing rest protects the neurochemical balance necessary for motivation. Mindfulness and meditation have been shown to enhance PFC function and reduce amygdala overactivity, improving emotional regulation and resilience.

Fourth, leveraging social connection and support activates oxytocin release and social reward systems, increasing commitment and enjoyment.

Finally, maintaining novelty and challenge in tasks keeps the brain’s prediction systems engaged, preventing habituation and boredom.

The Dark Side of Motivation: When Drive Becomes Destructive

While motivation is generally seen as positive, it can also lead to burnout, obsession, and risky behavior. The same dopamine-driven pursuit of reward that fuels creativity can also foster addiction, compulsive behaviors, or unethical actions when unchecked.

Understanding this darker side highlights the need for balance—between ambition and rest, between desire and wisdom. It also calls attention to mental health, as disorders like depression or ADHD involve disruptions in motivation circuits, manifesting as apathy or impulsivity.

Therapeutic interventions increasingly target these neural systems, using medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, and lifestyle changes to restore healthy motivation.

Motivation Across the Lifespan

Motivation evolves throughout life, influenced by developmental, hormonal, and experiential factors. Children exhibit high intrinsic motivation driven by curiosity and exploration, supported by brain plasticity.

Adolescence brings heightened sensitivity to social rewards and risks, linked to changes in the dopamine system. This explains teenagers’ intense drive for peer approval and new experiences.

In adulthood, motivation often shifts toward goal-oriented persistence, shaped by the prefrontal cortex’s maturation. In older age, motivation may decline due to changes in neurotransmitter function but can be maintained through engagement, learning, and social interaction.

Recognizing these patterns can guide tailored strategies for nurturing motivation at every stage of life.

The Future of Motivation Science

As neuroscience advances, new technologies such as functional MRI, optogenetics, and brain-computer interfaces deepen our understanding of motivation’s neural circuitry. Artificial intelligence models simulate motivational processes, opening possibilities for personalized interventions.

Emerging fields like neuroeconomics explore how decision-making and motivation intersect with economics and social behavior. This interdisciplinary approach promises to illuminate not only why we act but how to inspire collective progress.

Ultimately, the neuroscience of motivation invites us to see ourselves as dynamic beings, capable of change and growth, propelled by an intricate dance of biology and experience.

Conclusion: Embracing the Motivated Mind

Motivation is the essence of human agency. It is where biology meets meaning, where neurons give rise to dreams. Through the lens of neuroscience, we appreciate its complexity—the delicate balance of chemicals, circuits, and emotions that spark and sustain our drive.

By understanding motivation’s roots and rhythms, we gain the power not only to inspire ourselves but to nurture it in others. Whether seeking to conquer personal goals, lead teams, or foster innovation, the neuroscience of motivation offers a roadmap to the enduring flame within us all.

Motivation is not a mystery reserved for the gifted few; it is a universal, biological imperative shaped by our thoughts, feelings, and connections. It is, quite simply, the heart’s restless call to become more.