Deep inside the human brain, a quiet but constant conversation shapes who we are. Signals travel between regions, guiding perception, thought, and awareness. Among the most important of these exchanges is the dialogue between the thalamus and the cerebral cortex, a partnership long suspected to organize how cortical circuits take shape. Yet for decades, this interaction remained largely hidden from direct study in humans. Now, a Japanese research team has found a way to watch this conversation unfold, not inside a living brain, but within a carefully constructed model grown in the laboratory.

Using miniature, multi-region brain-like structures called assembloids, researchers at Nagoya University have successfully reproduced a human neural circuit in vitro. Their work demonstrates that the thalamus is not merely a passive relay station, but an active architect that shapes cell type-specific neural circuits in the human cerebral cortex. The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offer a rare glimpse into how human brain circuits form and mature, and why this process matters deeply for understanding neurodevelopmental disorders.

Why the Cortex Cannot Work Alone

The cerebral cortex is often described as the brain’s outer shell of intelligence, the site of perception, cognition, and higher-order processing. Yet the cortex does not function in isolation. It contains many different types of neurons, each with specific roles, and its ability to perform complex tasks depends on effective communication both within the cortex and with other brain regions.

When these circuits fail to develop properly, the consequences can be profound. Patients with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder exhibit disruptions in the structure and function of cortical neural circuits. These disruptions are not merely anatomical curiosities; they are linked to altered perception, cognition, and behavior. Understanding how cortical circuits normally form is therefore essential for uncovering the biological roots of such disorders and for developing new therapeutic strategies.

Animal studies, particularly in rodents, have shown that the thalamus plays a critical role in shaping cortical circuits. However, translating these findings to humans has proven difficult. Ethical and technical barriers make it nearly impossible to observe early neural circuit formation directly in the developing human brain. This gap has left scientists with an urgent question: does the human thalamus shape cortical circuits in the same way, and if so, how?

Building a Brain Dialogue from Stem Cells

To overcome these limitations, researchers turned to organoids, three-dimensional structures derived from stem cells that mimic aspects of human organs. In neuroscience, brain organoids have emerged as powerful tools, offering simplified yet biologically meaningful models of human brain tissue. However, a single organoid represents only one region. Neural circuits, by definition, arise from interactions between regions.

This is where assembloids enter the story. Created by physically combining two or more organoids, assembloids allow scientists to recreate interactions between distinct brain regions in vitro. Professor Fumitaka Osakada, graduate student Masatoshi Nishimura, and their colleagues used this approach to reconstruct the interaction between the thalamus and the cortex.

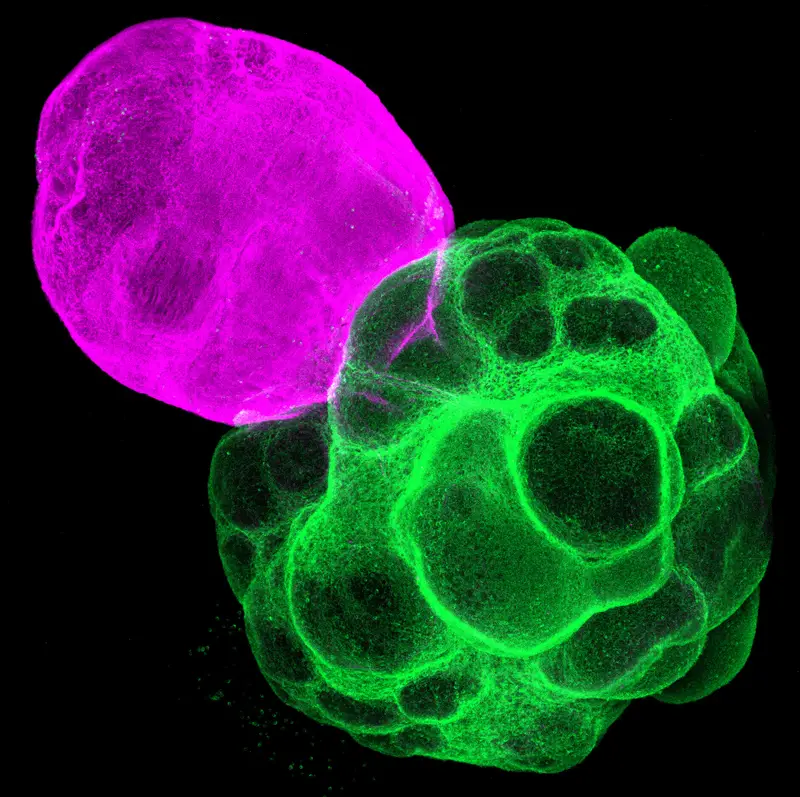

The team began with human induced pluripotent stem cells, which have the remarkable ability to develop into many different cell types. From these cells, they generated two separate organoids: one representing the cerebral cortex and the other representing the thalamus. By physically fusing these organoids, they created thalamus-cortex assembloids and began to observe how the two regions interacted over time.

When Two Miniature Brains Reach for Each Other

What the researchers saw was strikingly familiar. Axons from the thalamic side extended toward the cortex, while axons from the cortex reached back toward the thalamus. These growing fibers formed synapses, the specialized connections through which neurons communicate. The bidirectional growth and synaptic formation mirrored what is known to occur in the human brain during development.

This finding alone was significant. It demonstrated that thalamus-cortex interactions in the assembloid operate in a way that resembles their behavior in the human brain. The miniature system was not merely a static model but a dynamic one, capable of reproducing essential features of human neural circuit formation.

Yet structure is only part of the story. Neural circuits are defined not just by their connections but by their activity. The next question was whether these newly formed connections actually influenced how the cortex developed and functioned.

A Cortex That Grows Up Faster with a Thalamus Nearby

To probe this question, the researchers compared gene expression patterns in two conditions: the cortical side of the assembloid and a single cortical organoid grown without a thalamic partner. The differences were telling. The cortex within the assembloid showed signs of greater maturity than the isolated cortical organoid.

This suggested that interaction with the thalamus promotes cortical growth and maturation. In other words, the cortex does not simply develop according to an internal program. Its development is actively shaped by signals arriving from the thalamus, even in this simplified in vitro system.

The team then examined neural activity within the assembloid to understand how thalamus-cortex interactions contribute to circuit formation. They observed that neural activity propagated from the thalamus to the cortex in a wave-like pattern. As these waves spread, they helped organize the cortex into a synchronous network, with groups of neurons firing together in coordinated patterns.

Not All Neurons Listen the Same Way

The cerebral cortex contains multiple subtypes of excitatory neurons, each with distinct projection targets and functions. To understand which neurons were participating in the synchronized networks, the researchers focused on three primary subtypes: intratelencephalic, pyramidal tract, and corticothalamic neurons.

By measuring neural activity levels in each subtype, they uncovered a striking pattern. Synchronous activity was observed in pyramidal tract and corticothalamic neurons, both of which project to the thalamus. In contrast, intratelencephalic neurons showed no such synchrony.

This selective pattern revealed an important principle. Thalamic inputs do not simply increase activity across the cortex in a uniform way. Instead, they selectively promote synchronized networks among specific neuron types, particularly those that are functionally connected to the thalamus itself. Through this process, thalamic signals enhance the functional maturation of particular cortical circuits.

Why Recreating the Brain Matters

By successfully reproducing human neural circuits using assembloids, the research team has provided a powerful system for analyzing the origins, structures, and functions of these circuits at the level of individual cell types. This constructivist approach, building aspects of the human brain piece by piece, opens new possibilities for studying processes that were once inaccessible.

The implications extend far beyond basic curiosity. Disorders of brain development are rooted in disrupted circuit formation. Having a human-based model that captures region-specific interactions makes it possible to study how and where these processes go awry. It also offers a platform for testing potential interventions in a system that closely reflects human biology.

As Osakada explained, “We have made significant progress in the constructivist approach to understanding the human brain by reproducing it. We believe these findings will help accelerate the discovery of mechanisms underlying neurological and psychiatric disorders, as well as the development of new therapies.”

In revealing how the thalamus helps sculpt the cortex, this work brings scientists one step closer to understanding the intricate choreography that builds the human mind, and to finding ways to restore it when that choreography falters.

More information: Masatoshi Nishimura et al, Thalamus–cortex interactions drive cell type–specific cortical development in human pluripotent stem cell–derived assembloids, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2506573122