About a decade ago, a deceptively simple question began to glow in the minds of a small group of neuroscientists. They were surrounded by powerful lasers, intricate optical hardware, and established methods for watching neurons fire. Yet the question that lingered was almost childlike in its curiosity: what if the brain could light itself up?

“We started thinking: ‘What if we could light up the brain from the inside?'” said Christopher Moore, a professor of brain science at Brown University. The idea challenged a long-standing assumption in neuroscience, that to see brain activity, researchers must shine light into the brain from the outside. For decades, that external illumination had been both a gift and a burden, enabling discovery while imposing technical and biological limits.

Moore and his collaborators began to imagine an alternative inspired by nature itself. Instead of forcing light into delicate tissue, they wondered whether brain cells could be engineered to produce their own light, much like fireflies glowing on a summer night. That moment of curiosity marked the beginning of a journey that would eventually lead to a new way of seeing the living brain in action.

The Limits of Shining Light In

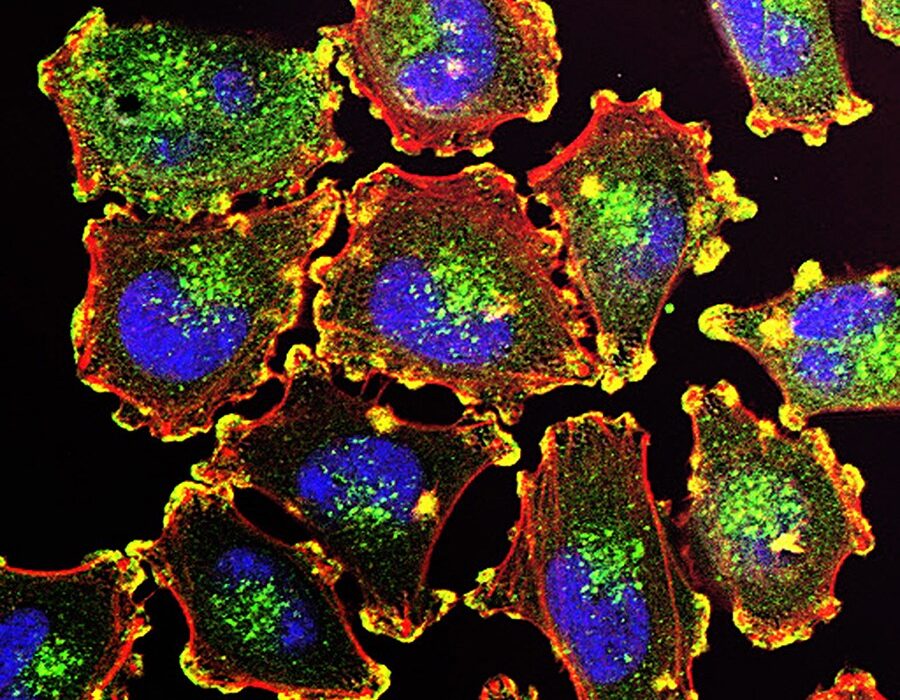

To understand why the idea mattered, it helps to understand how brain activity is usually measured. Neuroscientists often rely on fluorescence, a process in which molecules glow when illuminated by external light. These fluorescent signals can be made sensitive to calcium ions, which surge inside neurons when they become active. In this way, flashes of color reveal the rhythms of thought, sensation, and movement.

“In the way fluorescence works, you shine light beams at something, and you get a different wavelength of light beams back,” Moore explained. “You can make that process calcium-sensitive so you can get proteins that will shift back a different amount or different color of light, depending on whether or not calcium is present, with a bright signal.”

But that brightness comes at a cost. Prolonged exposure to intense light can damage living cells. Over time, fluorescent molecules can lose their ability to glow, a phenomenon known as photobleaching, which limits how long experiments can last. The hardware required to deliver light, including lasers and optical fibers, also makes experiments more invasive and technically demanding.

These constraints mean that many aspects of brain activity remain frustratingly out of reach. Long-term processes like learning or complex behavior unfold over hours, not minutes, and the tools used to watch neurons often cannot keep up without compromising the tissue itself.

A Hub Built Around a Glow

In 2017, the vision of lighting the brain from within found a formal home. The Bioluminescence Hub at Brown’s Carney Institute for Brain Science was launched through collaborations among Moore, Diane Lipscombe, the institute’s director, Ute Hochgeschwender at Central Michigan University, and Nathan Shaner at the University of California San Diego. Their shared goal was ambitious and precise: to develop and share neuroscience tools that give nervous system cells the ability to make and respond to light.

Bioluminescence offered a tantalizing alternative to fluorescence. Instead of relying on external illumination, bioluminescent systems produce light through a chemical reaction, typically when an enzyme breaks down a small molecule. This process requires no lasers and no intense light beams.

Because bioluminescent probes generate light internally, they avoid photobleaching entirely and do not carry the same risk of light-induced damage. In principle, this meant researchers could watch living cells for far longer, with less intrusion and greater safety.

Yet there was a problem that had stalled the field for decades. The light produced by bioluminescent systems simply was not bright enough to capture the fast, fine-grained details of brain activity. The idea was elegant, but the tools were dim.

The Molecule That Changed the Equation

That obstacle finally gave way with the development of a new molecular tool described in a study published in Nature Methods. The device is called the Ca2+ BioLuminescence Activity Monitor, or CaBLAM, and it represents a breakthrough in making bioluminescence practical for neuroscience.

Moore credits Nathan Shaner with leading the molecular design that made CaBLAM possible. “CaBLAM is a really amazing molecule that Nathan created,” Moore said. “It lives up to its name.”

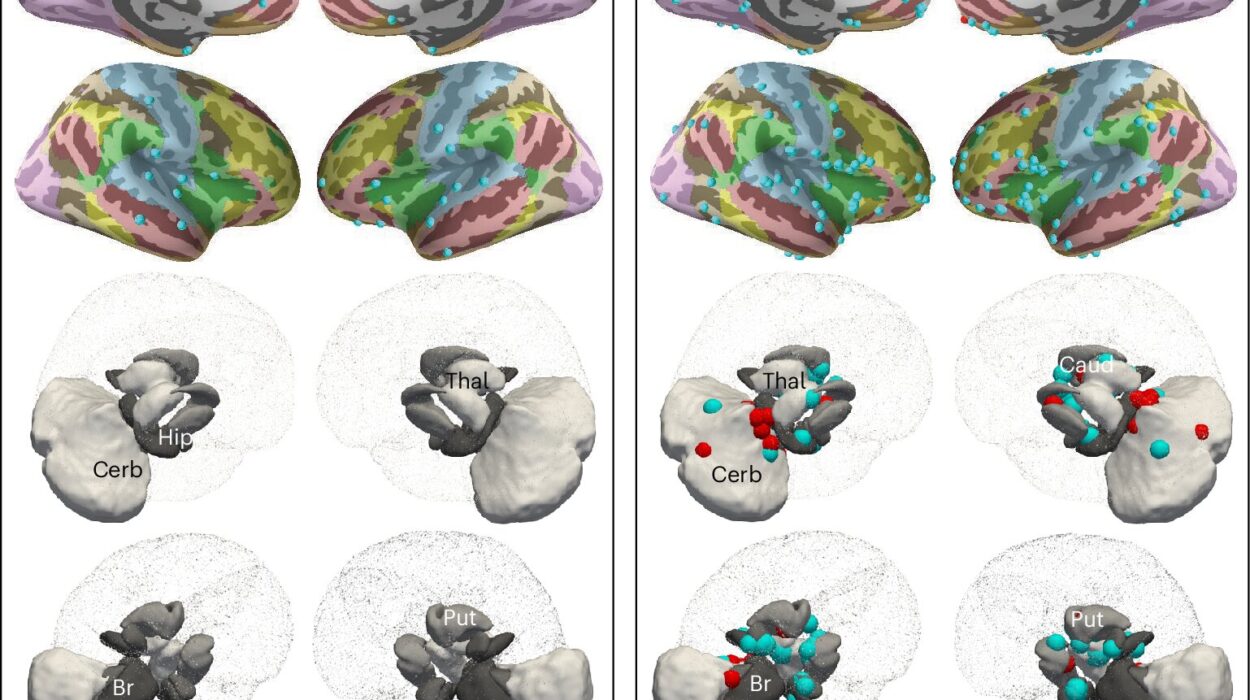

CaBLAM is designed to respond to calcium ions, the same biological signal used in fluorescent imaging, but it does so by emitting its own light. The result is a probe capable of capturing brain activity at high speed, down to the level of single cells and even subcellular compartments. In experiments with mice and zebrafish, CaBLAM enabled multi-hour recordings without the need for any external light source.

For the first time, bioluminescence was not merely an alternative. It was competitive, and in some respects superior.

Seeing Clearly Through the Brain’s Darkness

One of the most striking advantages of bioluminescence is not just what it avoids, but what it reveals. Brain tissue naturally glows faintly when struck by external light, creating a background haze that interferes with fluorescent signals. On top of that, tissue scatters light, blurring images and making it difficult to see deep structures clearly.

“Brain tissue already glows faintly on its own when hit by external light, creating background noise,” Shaner said. “On top of that, brain tissue scatters light, blurring both the light going in and the signal coming back out. This makes images dimmer, fuzzier, and harder to see deep inside the brain.”

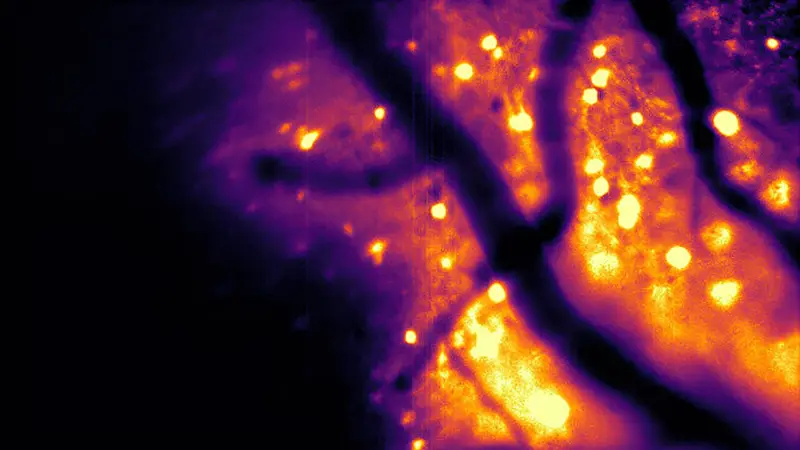

Bioluminescence changes that visual landscape entirely. Because the brain does not naturally produce bioluminescent light, engineered neurons glowing on their own appear against a nearly black background. There is little interference and far less scattering to contend with.

“The brain does not naturally produce bioluminescence, so when engineered neurons glow on their own, they stand out against a dark background with almost no interference,” Shaner said. “And with bioluminescence, the brain cells act like their own headlights: You only have to watch the light coming out, which is much easier to see even when scattered through tissue.”

The metaphor is apt. Instead of illuminating a foggy landscape from afar, researchers can now watch as individual cells switch on their own lamps.

Capturing Time as It Truly Unfolds

The impact of this clarity becomes most apparent over time. Moore emphasized that measuring ongoing activity in living brain cells is essential for understanding how biological organisms function. With CaBLAM, researchers can do something that was previously impossible.

“The current paper is exciting for a lot of reasons,” Moore said. “These new molecules have provided, for the first time, the ability to see single cells independently activated, almost as if you’re using a very special, sensitive movie camera to record brain activity while it’s happening.”

In the study, the team demonstrated a continuous recording session lasting five hours. Under fluorescent methods, photobleaching would have ended the experiment long before. With bioluminescence, the light kept coming, steady and reliable.

“For studying complex behavior or learning, bioluminescence allows one to capture the entire process, with less hardware involved,” Moore said. The brain could be observed as it truly works, not in fragments constrained by technology.

Why This Light Matters

CaBLAM is not an isolated achievement. It is part of a broader effort by the Bioluminescence Hub to reimagine how brain activity can be controlled and observed. One project allows a living cell to emit a burst of light detected by a neighboring cell, effectively enabling neurons to communicate through light, an idea Moore describes as “rewiring the brain with light.” Other efforts focus on using calcium not just as a signal to observe, but as a way to actively control cellular behavior.

As these ideas converged, the need for brighter, more sensitive calcium sensors became clear. CaBLAM emerged as a foundational piece, carefully engineered to support a wide range of future experiments. “We made sure that as a center that’s trying to push the field forward, we created the necessary component pieces,” Moore said.

Looking ahead, Moore believes the implications extend beyond neuroscience alone. “This advance allows a whole new range of options for seeing how the brain and body work,” he said, “including tracking activity in multiple parts of the body at once.”

The project itself stands as evidence of collaborative science, involving at least 34 researchers from Brown, Central Michigan University, U.C. San Diego, the University of California Los Angeles, and New York University. Together, they turned a decade-old question into a practical tool that illuminates life from within.

At its heart, this research matters because it changes how scientists can witness living systems. By letting cells speak in their own light, CaBLAM opens a clearer, gentler window into the dynamic processes that make brains, and bodies, come alive.

More information: Gerard G. Lambert et al, CaBLAM: a high-contrast bioluminescent Ca2+ indicator derived from an engineered Oplophorus gracilirostris luciferase, Nature Methods (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41592-025-02972-0