Gallstones are more than just small, pebble-like formations inside the body—they can be silent passengers in the gallbladder, or they can become painful, life-disrupting intruders. For some people, gallstones remain hidden, discovered only incidentally during scans for unrelated conditions. For others, they cause severe pain that radiates across the abdomen, disrupts digestion, and demands urgent medical attention.

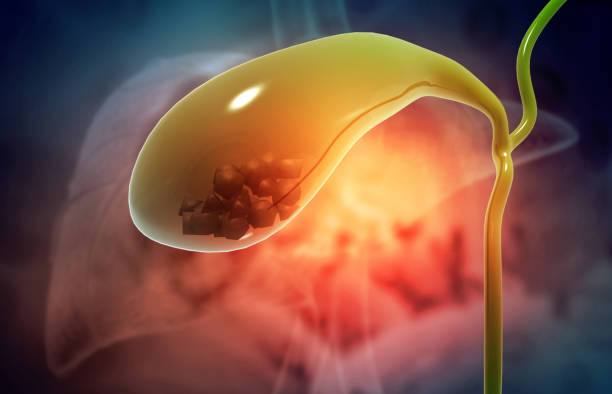

At their core, gallstones are hardened deposits that form inside the gallbladder—a small, pear-shaped organ nestled just beneath the liver. Though the gallbladder is modest in size, typically about four inches long, its role in digestion is significant. It stores and releases bile, a digestive fluid produced by the liver, which helps break down fats. When bile’s delicate chemical balance is disturbed, it can crystallize into gallstones, ranging from the size of a grain of sand to a golf ball.

Gallstones are common—so common, in fact, that tens of millions of people worldwide live with them, often unknowingly. In the United States alone, it is estimated that about 10–15% of adults have gallstones, with women and older adults being disproportionately affected. Yet, common does not mean harmless. When gallstones cause symptoms, they can lead to serious complications such as infection, pancreatitis, or even life-threatening blockages.

To understand gallstones is to look at the intersection of biology, lifestyle, and genetics. Their story is not simply about stones but about how the body maintains (or fails to maintain) balance in its most basic processes.

The Gallbladder and the Role of Bile

The gallbladder may be small, but it is an elegant part of the digestive system. Its primary job is storage and release. Throughout the day, the liver continuously produces bile, a yellow-green liquid made up of bile salts, cholesterol, bilirubin, water, and electrolytes. Rather than letting bile flood the intestines continuously, the body uses the gallbladder as a reservoir.

When we eat a meal—especially one rich in fats—the hormone cholecystokinin signals the gallbladder to contract, squeezing bile through the cystic duct and into the small intestine. There, bile salts emulsify fats, breaking them down into smaller droplets that enzymes can digest more effectively.

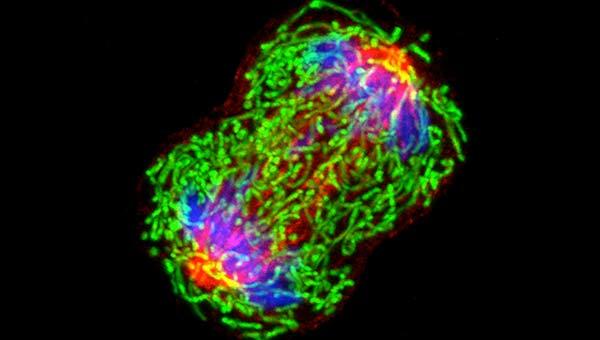

This system works beautifully most of the time. But when bile’s chemical makeup changes—when it contains too much cholesterol, too much bilirubin, or too little bile salts—its ingredients can precipitate out, forming crystals. Over time, these crystals grow and clump together, creating gallstones.

What Causes Gallstones?

Gallstones do not have a single cause; instead, they emerge from a complex interplay of chemical, genetic, and lifestyle factors. Scientists understand several main contributors:

Cholesterol Imbalance in Bile

One of the leading causes is excess cholesterol in bile. Normally, bile salts and lecithin dissolve cholesterol. But when cholesterol levels become too high, the bile can no longer keep it dissolved. Crystals form, which may eventually grow into gallstones.

Excess Bilirubin

Bilirubin is a yellow substance formed when red blood cells break down. Conditions that cause increased red blood cell destruction—such as sickle cell anemia, cirrhosis, or certain infections—lead to higher bilirubin levels. Excess bilirubin in bile contributes to pigment gallstones.

Poor Gallbladder Emptying

If the gallbladder does not empty fully or often enough, bile becomes stagnant, increasing the risk of stone formation. This sluggish emptying may result from fasting, pregnancy, or certain medical conditions.

Risk Factors That Raise Susceptibility

- Gender and Hormones: Women, especially those who are pregnant, taking estrogen therapy, or using oral contraceptives, have higher risks due to hormonal influences on cholesterol metabolism.

- Age: Gallstones become more common with age, especially after 40.

- Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome: Excess weight increases cholesterol in bile and slows gallbladder emptying.

- Rapid Weight Loss: Losing weight quickly, whether through strict dieting or bariatric surgery, paradoxically increases gallstone risk. The liver secretes more cholesterol during rapid fat breakdown, overwhelming bile’s ability to dissolve it.

- Diet: Diets high in refined carbohydrates and low in fiber may increase risk, whereas diets rich in healthy fats, whole grains, and plant-based foods may protect against gallstones.

- Family History: Genetics also play a role. If your parents or siblings had gallstones, your risk is higher.

- Medical Conditions: Diabetes, liver disease, and certain intestinal conditions (such as Crohn’s disease) can predispose individuals to gallstones.

The story of gallstone formation is, therefore, not one of chance but of cumulative influences. A combination of biology, lifestyle, and genetics determines whether the gallbladder remains clear or becomes a stone-forming reservoir.

Symptoms of Gallstones

Gallstones are often called “silent stones” because many people never know they have them. These asymptomatic gallstones can remain undetected for years, discovered only during ultrasounds, CT scans, or MRIs performed for unrelated reasons.

But when gallstones block the ducts that carry bile, they produce noticeable and often severe symptoms. The hallmark symptom is biliary colic, a type of pain that:

- Typically arises suddenly and intensifies over minutes.

- Is felt in the upper right abdomen, just under the ribs, though it may radiate to the back or right shoulder blade.

- Can last from several minutes to a few hours.

- Is often triggered by fatty meals, though it may occur spontaneously.

Other symptoms that may accompany gallstones include:

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Indigestion, bloating, and burping.

- Intolerance to fatty foods.

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), if a stone blocks the common bile duct.

- Fever and chills, which may signal infection (cholecystitis).

The pain of gallstones is unique. Patients often describe it as intense, stabbing, or squeezing. Unlike indigestion, it does not improve with antacids, rest, or positional changes.

Complications of Gallstones

Not all gallstones remain benign. When they obstruct the bile ducts or irritate the gallbladder, they can trigger dangerous complications:

- Cholecystitis (Gallbladder Inflammation): A gallstone lodged in the cystic duct can cause the gallbladder to become inflamed and infected, leading to severe pain, fever, and tenderness.

- Choledocholithiasis (Stones in the Common Bile Duct): Stones that migrate into the common bile duct can block the flow of bile, leading to jaundice, infection, and even liver damage.

- Pancreatitis: If a stone blocks the pancreatic duct, digestive enzymes back up into the pancreas, causing painful and potentially life-threatening inflammation.

- Gallbladder Cancer: Though rare, long-standing gallstones are associated with a slightly increased risk of gallbladder cancer.

These complications underscore why gallstones cannot always be ignored. Silent stones may be left alone, but symptomatic or complicated gallstones often require medical intervention.

How Gallstones Are Diagnosed

Accurate diagnosis is essential for effective treatment. Physicians use a combination of patient history, physical examination, and imaging studies.

Patient History and Examination

Doctors begin by asking about pain characteristics, diet, family history, and other risk factors. A physical examination may reveal tenderness in the upper right abdomen, particularly when the doctor presses under the ribs while the patient inhales (Murphy’s sign, a classic indicator of gallbladder inflammation).

Imaging Tests

- Ultrasound: The most common and reliable first test. It can detect gallstones, gallbladder wall thickening, and signs of inflammation.

- CT Scan: Less sensitive for gallstones but useful for ruling out other abdominal conditions.

- MRI and MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography): These provide detailed images of bile ducts, helpful in diagnosing stones in the common bile duct.

- HIDA Scan (Hepatobiliary Iminodiacetic Acid Scan): A nuclear medicine test that evaluates gallbladder function and can detect blockages.

Blood Tests

While blood tests cannot confirm gallstones, they help detect complications by revealing signs of infection, liver dysfunction, or pancreatitis.

Treatment Options for Gallstones

Treatment depends on whether gallstones are causing symptoms.

Asymptomatic Gallstones

If gallstones are silent, doctors often recommend a watchful waiting approach. Many people live their whole lives without gallstone-related problems.

Symptomatic Gallstones

When gallstones cause pain or complications, treatment becomes necessary.

Surgery: The Gold Standard

- Cholecystectomy (Gallbladder Removal): The most definitive treatment. Today, it is most often performed laparoscopically, through small incisions, leading to faster recovery and less pain.

- Open Cholecystectomy: Required in rare cases with severe infection, extensive scarring, or complications.

After gallbladder removal, bile flows directly from the liver to the small intestine. Most people digest normally, though some may notice changes in fat digestion or bowel habits.

Non-Surgical Options

- Oral Dissolution Therapy: Medications such as ursodeoxycholic acid can dissolve cholesterol stones, but treatment takes months or years and stones often recur.

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy: Rarely used, this method uses sound waves to break stones into smaller pieces.

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): A specialized procedure used to remove stones from the common bile duct.

Non-surgical methods are typically reserved for patients who cannot undergo surgery due to other health conditions.

Living Without a Gallbladder

Many patients wonder: “What happens if I lose my gallbladder?” Fortunately, the human body adapts well. Without the gallbladder, bile flows directly from the liver to the intestine. Some individuals experience temporary diarrhea or difficulty digesting fatty meals, but most adjust over time.

Lifestyle adjustments—such as eating smaller, more frequent meals and avoiding excessive fatty foods—can help ease digestion after surgery.

Preventing Gallstones

While not all gallstones can be prevented, certain strategies reduce risk:

- Maintaining a healthy weight through balanced diet and regular activity.

- Avoiding rapid weight loss.

- Eating a diet rich in fiber, fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats.

- Staying physically active.

Prevention is about maintaining balance—ensuring that bile’s chemistry remains stable and that the gallbladder empties regularly and effectively.

The Emotional and Human Side of Gallstones

Beyond the clinical details, gallstones affect lives in personal and emotional ways. The pain of biliary colic can be frightening and debilitating. Uncertainty about when the next attack will strike can create anxiety. For some, surgery brings relief but also fear about living without an organ.

Stories from patients often reveal resilience. A woman who suffered repeated night-time attacks describes the relief and freedom she felt after gallbladder surgery. A man with silent stones discovered during a routine ultrasound speaks of gratitude for early detection. These human experiences remind us that gallstones are not just medical conditions—they are lived realities that touch people’s sense of safety, comfort, and confidence in their own bodies.

The Future of Gallstone Research and Treatment

Medical science continues to explore new ways to prevent and treat gallstones. Advances in imaging allow earlier and more accurate diagnosis. Researchers are studying genetic markers that predict who is most at risk. New medications may one day provide alternatives to surgery, dissolving stones more effectively or preventing them altogether.

Personalized medicine—tailoring treatments based on individual genetics and lifestyle—may transform gallstone care in the future. Imagine a day when a simple blood test can reveal a person’s likelihood of developing gallstones, allowing preventive steps long before symptoms arise.

Conclusion: A Balance Disrupted, A Balance Restored

Gallstones remind us of the delicate equilibrium within the body. A tiny imbalance in bile chemistry can produce stones that, though small, create outsized effects on health. Yet medicine offers solutions—from lifestyle changes to advanced surgeries—that restore balance and relieve suffering.

Ultimately, gallstones are not just about stones in an organ; they are about the body’s remarkable systems of digestion, resilience, and adaptation. To understand gallstones is to appreciate both the fragility and the strength of human health—and to recognize the ways science and compassion together can turn pain into healing.