Few medical conditions are as vividly memorable as kidney stones. People who have experienced them often describe the pain as one of the most excruciating sensations imaginable—comparable, some say, to childbirth or even worse. The agony can strike suddenly, radiating from the back to the abdomen or groin, leaving one doubled over in desperation. Yet kidney stones are more than just a painful inconvenience. They represent a fascinating, complex interplay of biology, chemistry, and lifestyle that, when disrupted, transforms something as simple as dissolved minerals in urine into sharp, solid crystals capable of causing immense suffering.

Kidney stones have been with humanity since ancient times. Archaeologists have found evidence of stones in Egyptian mummies dating back over 4,000 years. Despite advances in medicine, they remain a growing global health issue, affecting millions each year, with prevalence rising due to diet, dehydration, and sedentary lifestyles. To understand them fully, we must explore what they are, why they form, how they reveal themselves, and what can be done to treat and prevent them.

What Are Kidney Stones?

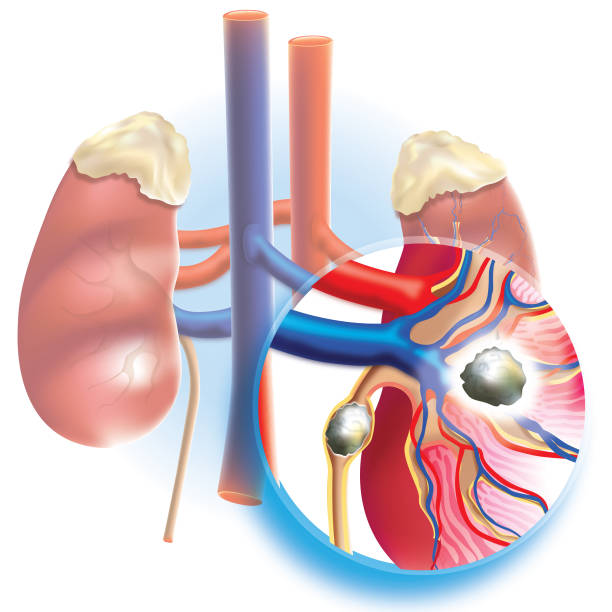

At their core, kidney stones (also called renal calculi, nephroliths, or uroliths) are solid masses made of minerals and salts that crystallize inside the urinary tract. Normally, urine contains substances—such as citrate and magnesium—that prevent these crystals from clumping together. But when the balance of water, salts, and minerals is disrupted, crystals can form and stick, gradually growing into stones.

These stones can range in size from a grain of sand to a golf ball. Some remain in the kidney without causing problems, while others travel into the ureter—the narrow tube connecting kidney and bladder—where they can block urine flow and trigger intense pain.

Types of Kidney Stones

Kidney stones are not all the same. Their composition reflects the underlying imbalance that caused them, which has important implications for treatment and prevention.

- Calcium Oxalate Stones: The most common type, formed when calcium combines with oxalate in urine. High oxalate foods, such as spinach, nuts, and chocolate, along with low fluid intake, increase risk.

- Calcium Phosphate Stones: Less common but often associated with conditions that raise urine pH, such as certain kidney disorders.

- Uric Acid Stones: Develop when urine is too acidic, often in people with high-protein diets, gout, or metabolic syndrome.

- Struvite Stones: Usually linked to urinary tract infections. They can grow quickly and become large, sometimes filling the kidney (staghorn calculi).

- Cystine Stones: Rare, caused by a genetic condition called cystinuria, which leads to excess cystine in urine.

Causes of Kidney Stones

The formation of kidney stones is rarely due to a single factor. Instead, it is the result of multiple influences—biological, environmental, and lifestyle—that converge to create the perfect storm for crystallization.

1. Dehydration

Water is the most important safeguard against stones. When fluid intake is insufficient, urine becomes concentrated, allowing minerals to collide and crystallize. Hot climates, heavy sweating, and inadequate hydration all raise the risk.

2. Dietary Habits

Modern diets play a significant role. Excessive consumption of sodium increases calcium excretion, while high intake of oxalate-rich foods can overload natural defenses. High animal protein diets produce uric acid and reduce citrate levels, tipping the balance toward stone formation.

3. Genetics

Family history matters. If a parent or sibling has had kidney stones, the likelihood of developing them increases. Rare genetic disorders, like cystinuria, directly cause certain stone types.

4. Medical Conditions

Obesity, diabetes, hyperparathyroidism, gout, and chronic kidney disease all alter the body’s chemistry in ways that encourage stones. Recurrent urinary tract infections can lead to struvite stones.

5. Medications and Supplements

Certain drugs, such as diuretics, antacids, and excessive vitamin D or calcium supplements, may raise stone risk.

Symptoms of Kidney Stones

The hallmark of kidney stones is pain—sudden, severe, and unforgettable. Yet not all stones cause symptoms. A small stone may pass unnoticed, while larger ones cause dramatic, debilitating episodes.

Common symptoms include:

- Renal Colic: Sudden waves of intense pain radiating from the back or side to the lower abdomen and groin. The pain often comes in cycles as the ureter contracts around the stone.

- Hematuria (Blood in Urine): Urine may appear pink, red, or brown due to tiny injuries from the stone.

- Frequent Urination: A constant urge, especially when the stone nears the bladder.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Caused by the body’s visceral reaction to pain and obstruction.

- Cloudy or Foul-Smelling Urine: Possible sign of infection alongside stones.

- Fever and Chills: If present, these indicate a dangerous infection requiring urgent care.

How Kidney Stones Are Diagnosed

Diagnosis begins with suspicion. A person presenting with sudden, severe flank pain often leads doctors to consider kidney stones. But confirmation requires tests to pinpoint size, type, and location.

- Imaging: The gold standard is a non-contrast CT scan, which detects almost all stones with precision. Ultrasound is often used, especially for pregnant women, though it is less sensitive. X-rays can identify some stones but miss others.

- Urinalysis: Reveals blood, infection, or crystals, offering clues about stone type.

- Blood Tests: Check kidney function and levels of calcium, uric acid, and electrolytes.

- Stone Analysis: If a stone is passed or surgically removed, its composition is analyzed to guide prevention.

- Metabolic Evaluation: For recurrent stone formers, 24-hour urine collection helps uncover risk factors, such as high calcium, oxalate, or low citrate levels.

Treatment of Kidney Stones

Treatment depends on stone size, type, location, and the severity of symptoms. Some stones pass spontaneously, while others require medical or surgical intervention.

Conservative Management

For small stones (usually under 5 mm), the first approach is often watchful waiting, with pain control and hydration. Patients are advised to drink plenty of fluids to flush the urinary tract. Medications called alpha-blockers (such as tamsulosin) can relax the ureter, making it easier for stones to pass.

Pain Management

Renal colic demands relief. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen are highly effective, reducing both pain and inflammation. In severe cases, opioids may be used.

Surgical Options

When stones are too large to pass or cause complications, intervention becomes necessary.

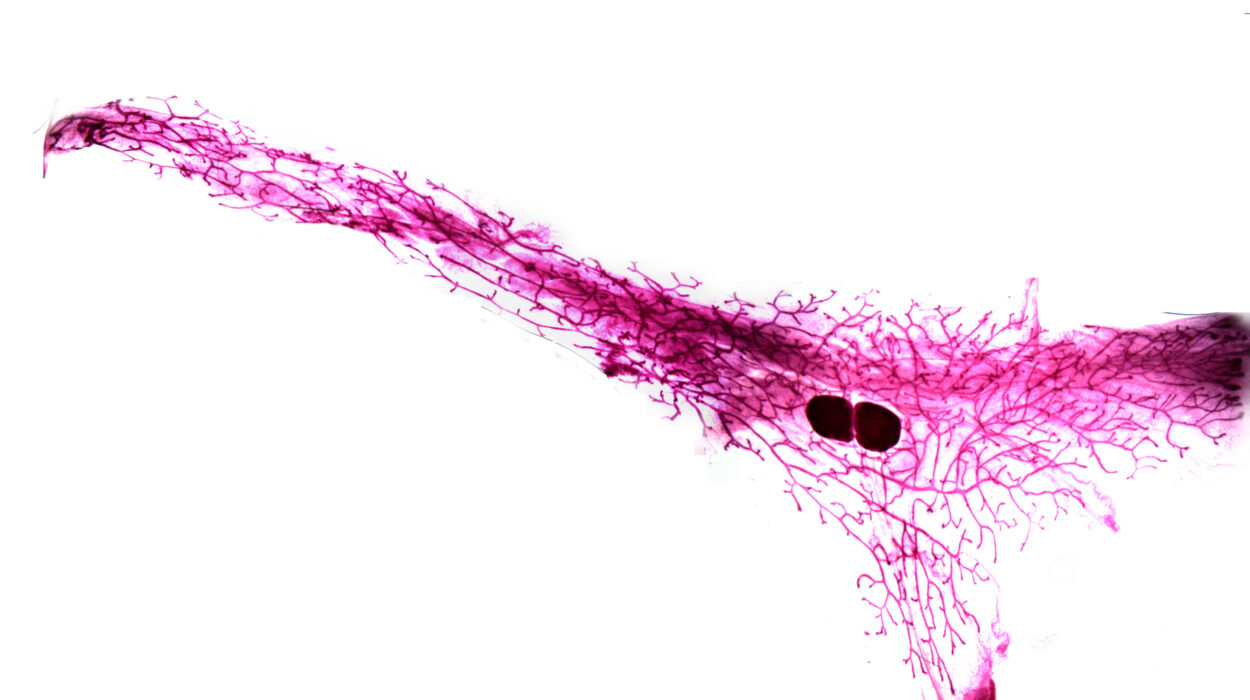

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL): High-energy sound waves break stones into fragments that can pass naturally. Best for small-to-medium stones.

- Ureteroscopy: A thin scope is passed into the ureter to locate and remove or laser-fragment stones. Effective for stones lodged in the ureter.

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL): For very large stones, a small incision in the back allows direct removal from the kidney.

- Open Surgery: Rare today, used only in exceptional cases when other methods fail.

Treating Underlying Causes

If an underlying medical condition is responsible—such as hyperparathyroidism or chronic infection—addressing it is crucial to prevent recurrence.

Preventing Kidney Stones

Prevention is the cornerstone of long-term management, especially for people who suffer recurrent stones. It focuses on restoring balance in the body’s chemistry.

- Stay Hydrated: Drinking enough fluids—about 2–3 liters daily—dilutes urine, lowering stone risk.

- Dietary Adjustments:

- Moderate salt intake to reduce calcium excretion.

- Maintain normal dietary calcium (not too low, not excessive), as calcium binds oxalate in the gut.

- Limit high-oxalate foods if prone to oxalate stones.

- Eat more fruits and vegetables, which provide citrate, a natural inhibitor of stone formation.

- Limit animal protein if prone to uric acid stones.

- Medications: Depending on stone type, doctors may prescribe potassium citrate, thiazide diuretics, or allopurinol to prevent recurrence.

Complications of Kidney Stones

While many stones pass without lasting harm, complications can be serious if left untreated. Obstruction can damage the kidney, recurrent stones may scar tissue, and infections can become life-threatening if bacteria spread into the bloodstream. Chronic kidney disease and even kidney failure can result in severe, untreated cases.

Living with Kidney Stones: The Human Experience

Beyond science and treatment, kidney stones profoundly affect quality of life. Patients often describe fear of recurrence, lifestyle disruptions, and psychological stress. The pain is so intense that it leaves lasting memories, shaping how people approach hydration, diet, and self-care. Support from family, access to healthcare, and proper education play vital roles in helping patients cope.

The Future of Kidney Stone Management

Medical research is advancing toward more personalized prevention and treatment. Genetic studies aim to identify people at high risk, while nanotechnology and improved imaging promise more precise interventions. Efforts are also underway to develop drugs that directly target the biochemical pathways of stone formation.

At the same time, public health efforts—encouraging hydration, balanced diets, and early medical care—remain essential to reducing the global burden of kidney stones.

Conclusion: From Pain to Prevention

Kidney stones are, at once, a biological puzzle and a deeply human experience of suffering. They remind us of the delicate balance required to maintain health and the immense power of something as simple as water to protect us. While the pain of stones is unforgettable, so too is the resilience of those who endure them and the progress of medicine in offering relief and hope.

To understand kidney stones is to see the body not as a static structure but as a living chemistry set, constantly balancing inputs and outputs. When the balance falters, crystals form, pain erupts, and life is interrupted. But through awareness, prevention, and treatment, the story of kidney stones can shift from one of agony to one of empowerment—proof that even in the most painful conditions, knowledge and care can restore health and peace.