For decades, climate scientists have watched the planet warm. Thermometers rise. Ice retreats. Heatwaves intensify. The story seems clear—until it isn’t.

Because in one vast stretch of ocean, the script flipped.

In the eastern tropical Pacific and the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean, temperatures have been doing something unexpected over the past 45 years. Instead of warming along with the rest of the globe, these waters have cooled. The phenomenon became known as the “Pacific puzzle.” And it has haunted climate science for more than a decade.

Now, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology believe they have taken a decisive step toward solving it.

Their findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, do more than resolve a curiosity. They illuminate hidden mechanisms within Earth’s climate system—and may restore confidence in how we predict the planet’s future.

A Cooling That Shouldn’t Exist

Global warming is not subtle. Across continents and oceans, temperatures have climbed steadily. Climate models have long captured this broad upward trend. These models, particularly those used in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) and incorporated into reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, form the backbone of international climate assessments.

Yet they share a blind spot.

They fail to reproduce the persistent cooling observed in the eastern tropical Pacific and parts of the Southern Ocean. For years, scientists proposed hypotheses. Perhaps it was natural variability. Perhaps ocean circulation quirks. But no explanation fully accounted for the pattern. And more importantly, no simulation successfully recreated it.

This gap mattered deeply.

The tropical Pacific sea surface temperature (SST) is not just a regional detail. It influences rainfall, atmospheric circulation, and even the overall pace of global warming. If models cannot reproduce past trends in this critical region, how confident can we be in their near-term predictions?

The World Climate Research Program identified the Pacific puzzle as one of the most pressing challenges in climate science.

Something fundamental was missing.

A Model That Sees What Others Cannot

The breakthrough came not from a new theory alone, but from a new way of seeing.

At the Max Planck Institute, a team led by Sarah Kang, director of the institute, turned to a next-generation climate model known as ICON. What makes ICON different is its remarkable resolution: 5 kilometers in the ocean and 10 kilometers in the atmosphere.

That level of detail changes everything.

Traditional climate models divide the planet into large grid boxes, averaging conditions across wide areas. Important small-scale processes blur together. But ICON’s finer grid allows it to simulate physical processes more explicitly—processes that were previously smoothed out or parameterized.

When researchers ran the simulation, something astonishing happened.

For the first time, a climate model successfully reproduced the observed cooling pattern in the Pacific.

It was not an approximation. It was not an artifact. It was a realistic simulation of the very trend that had eluded scientists for years.

And within that success lay the explanation.

The Invisible Swirls Beneath the Surface

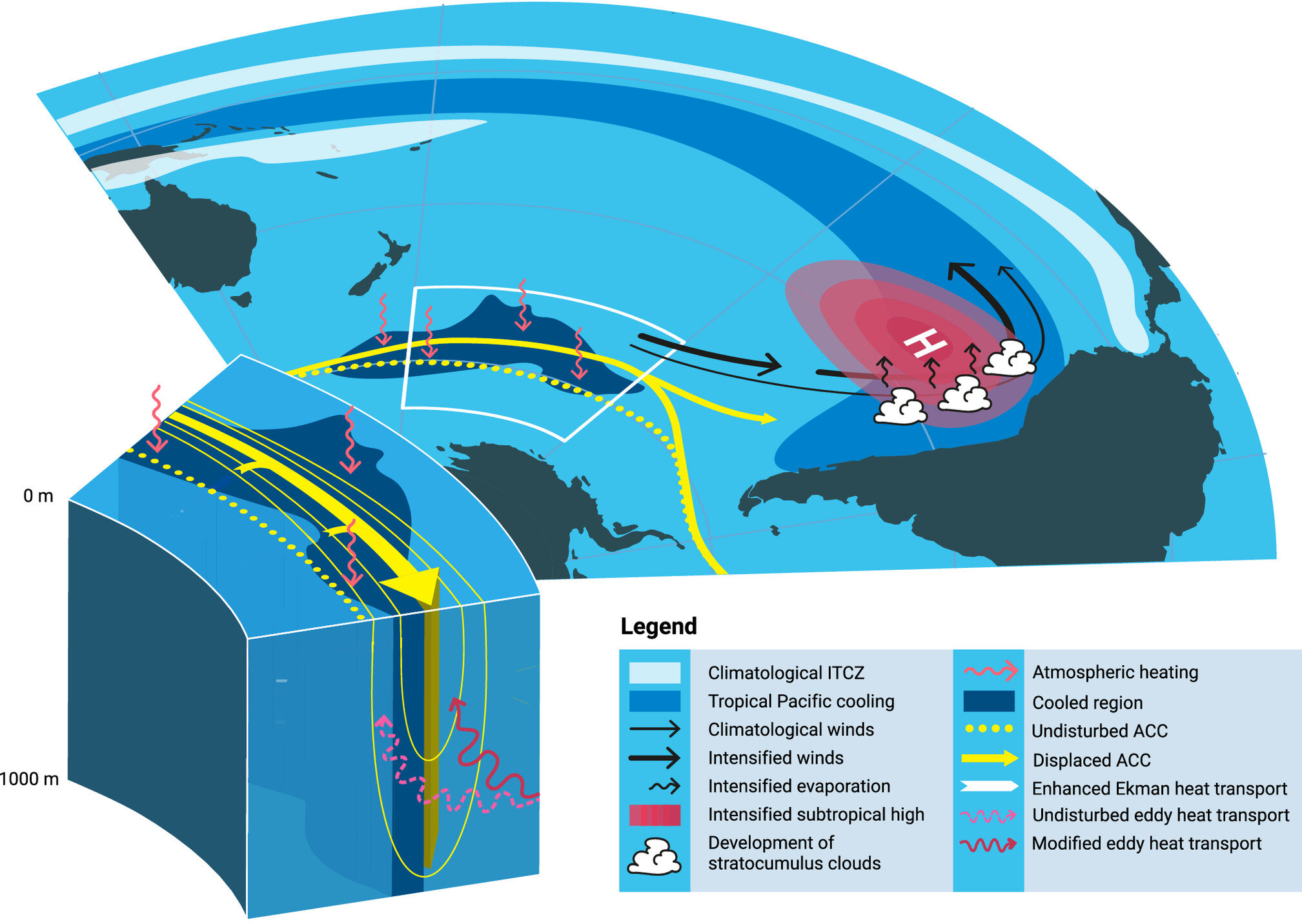

The story begins in the Southern Ocean, where powerful currents circle Antarctica. Among them is the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), a vast ribbon of water separating the Pacific from the Southern Ocean.

In these turbulent waters, countless swirling structures spin constantly. These are mesoscale ocean eddies, typically only a few tens of kilometers wide. Though small compared to ocean basins, they are mighty in influence.

In coarser CMIP models, these eddies are not explicitly represented. But in ICON, with its 5-kilometer ocean grid, they come alive.

Below the ocean surface, these eddies transport heat poleward across the ACC. They act as moving conveyors of warmth. But the simulation revealed a subtle shift: as the atmosphere warms, the poleward heat transport by these eddies weakens.

At the same time, excess heat delivered by the atmosphere does not linger. Instead, the ACC swiftly transports it away to other ocean basins.

This interplay sets off a chain reaction.

The upper 2,000 meters of water in the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean cool. The ACC shifts northward. Polar waters expand their reach.

It is not a simple story of warming everywhere. It is a story of dynamic rearrangement—of heat redistributed by invisible forces beneath the waves.

A Signal Travels North

The cooling does not remain confined to the Southern Ocean.

Through interconnected oceanic and atmospheric pathways, the signal travels northward into the subtropical Pacific. There, it strengthens an already existing high-pressure anomaly off the South American coast.

As this high-pressure system intensifies, so do the southeasterly trade winds blowing toward the equator.

These winds cool the sea surface in two ways. First, by increasing evaporation, they draw heat away from the ocean. Second, they promote the formation of low stratocumulus clouds—thick, reflective cloud layers that bounce incoming solar radiation back into space.

The cooling feeds on itself.

And here lies another critical piece of the puzzle.

Clouds That Tip the Balance

Cloud feedback has long been one of the most challenging aspects of climate modeling. In many CMIP models, the cloud response in this region is too weak to amplify cooling to the magnitude observed.

In ICON, however, the feedback is strong enough.

Its fine grid allows greater variation within individual cells, rather than averaging over broad areas. This means cloud formation and wind systems can be simulated with sharper intensity.

Even the rugged terrain of the Andes mountains is better represented. That improved depiction matters. The Andes help shield cool waters from easterly airflow over the Amazon and shape coastal wind systems—conditions that favor the formation of low clouds.

In ICON, these geographical and atmospheric details align realistically.

The result is a sufficiently strong cloud feedback that amplifies the cooling of the eastern tropical Pacific to match observations.

What once seemed like an inexplicable anomaly now emerges as the product of interacting processes—eddies, currents, winds, clouds, and mountains—all working together.

The Power of Collaboration and Technology

This achievement did not arise in isolation.

The research effort drew from across all departments of the institute—modelers, atmospheric researchers, and oceanographers collaborating closely. Sarah Kang described it as an efficient and fantastic project whose result is outstanding.

The technical capability to run such high-resolution simulations became possible through European initiatives, including European Eddy-Rich Earth System Models (EERIE), Next Generation Earth Model Systems (nextGEMS), and the WarmWorld project.

High-resolution modeling, Kang cautions, is not a universal solution. But in this case, it revealed a mechanism that had previously been inaccessible—one rooted in processes not explicitly represented in coarser models.

The next step, researchers say, is to determine which specific features of ICON drive the improvement and whether they offer new insights into future climate projections.

Why This Breakthrough Matters

The Pacific puzzle was more than an academic curiosity. It was a crack in the foundation of climate confidence.

If models cannot reproduce key historical patterns, especially in regions that influence global climate behavior, uncertainty spreads. Policymakers depend on near-term predictions for adaptation planning. Communities rely on regional projections to prepare for heat, rainfall shifts, and ocean changes.

By successfully reproducing the observed cooling in both the eastern tropical Pacific and the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean, this research strengthens trust in climate simulations—at least when they incorporate the necessary physical detail.

More importantly, it reminds us that Earth’s climate is not a simple thermostat turning steadily upward. It is a dynamic, interconnected system where warming can produce regional cooling through intricate pathways.

The ocean is not passive. The atmosphere is not uniform. Small-scale processes—eddies only tens of kilometers wide, clouds drifting low over coastal waters—can shape global patterns.

For years, the Pacific puzzle stood as a symbol of what climate science did not yet understand. Now, thanks to sharper resolution and deeper collaboration, a hidden mechanism has come into view.

The cooling waters were never contradicting global warming. They were revealing the complexity beneath it.

And in understanding that complexity, we take a step closer to seeing the future clearly.

Study Details

Sarah M. Kang et al, Km-scale coupled simulation and model–observation SST trend discrepancy, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2026). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2522161123