In the quiet language of mathematics, a team of biophysicists has uncovered a restless secret hidden inside living matter. What they found challenges a simple assumption: that structural flaws are passive scars in a material’s fabric. Instead, these flaws—known as topological defects—can move with purpose, shaping the very tissues they inhabit.

Published in Physical Review Letters, the new study introduces a mathematical model that reframes how we understand the forces sculpting biological tissues. At its heart lies a deceptively simple idea: sometimes, it is the imperfections that lead.

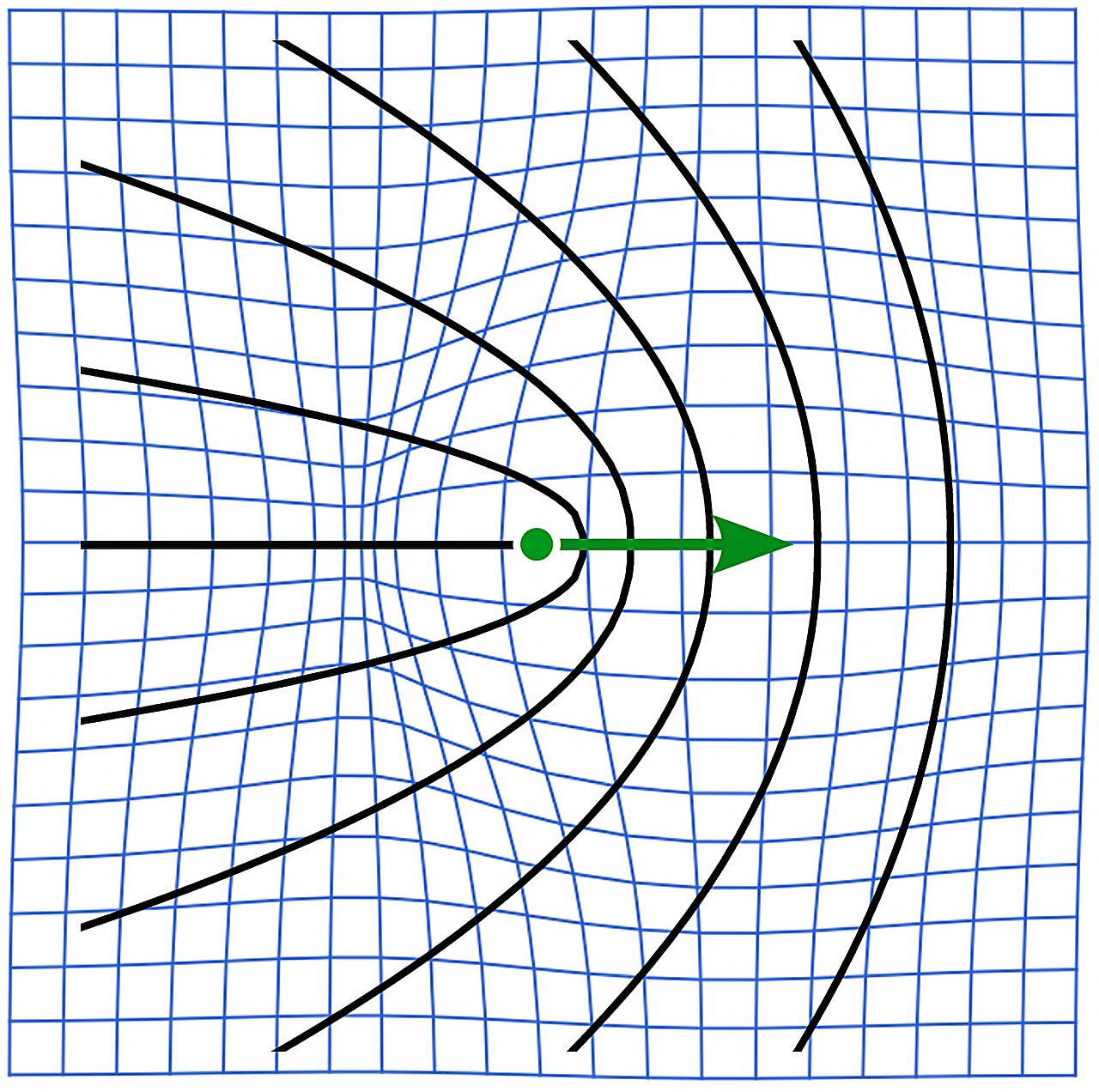

Topological defects arise when particles in a system attempt to arrange themselves in incompatible ways. Imagine countless tiny elements, each trying to align with its neighbors, but unable to agree on a single orientation. The result is a structural mismatch—a defect—not as a flaw of failure, but as a natural outcome of competing order.

For years, scientists have observed these defects in many systems, both natural and engineered. But in living tissues, their role has remained mysterious. Until now.

The Secret Life of Active Matter

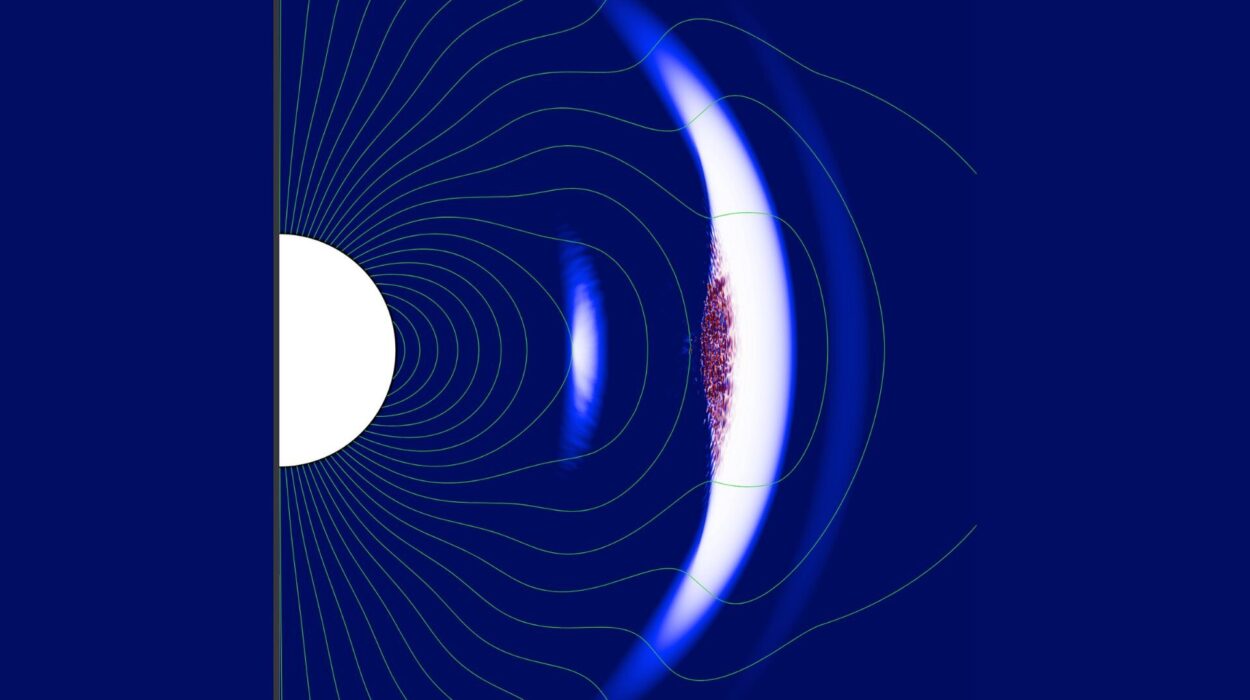

To understand why these defects matter, we must first step into the strange world of active fluids. These are not ordinary liquids. Their particles do not simply drift along passively. Instead, they harvest energy from their surroundings and convert it into motion. Each microscopic unit becomes a tiny engine, generating its own propulsion.

This internal drive gives rise to remarkable phenomena. In active systems, motion does not require an external push. It emerges from within, powered by molecular machinery. According to Fridtjof Brauns of the University of California Santa Barbara, who led the research, “Such active systems are driven by internal forces, generated by molecular motors.”

Those internal forces can produce swirling, chaotic patterns known as active turbulent flows. Even more intriguingly, they can create self-propelled topological defects—imperfections that do not simply sit still but travel through the material, concentrating mechanical stress as they go.

These ideas are not confined to biology. The same physics helps describe how liquid crystal displays function. In the thin layers of rod-shaped molecules inside our screens, topological defects influence how light is modulated, shaping the colors and images we see every day. It is a reminder that the boundary between living tissue and digital technology is thinner than it appears—both are governed by the same fundamental principles of organization and disruption.

Yet living tissues present a new twist.

When Solids Behave Like Living Things

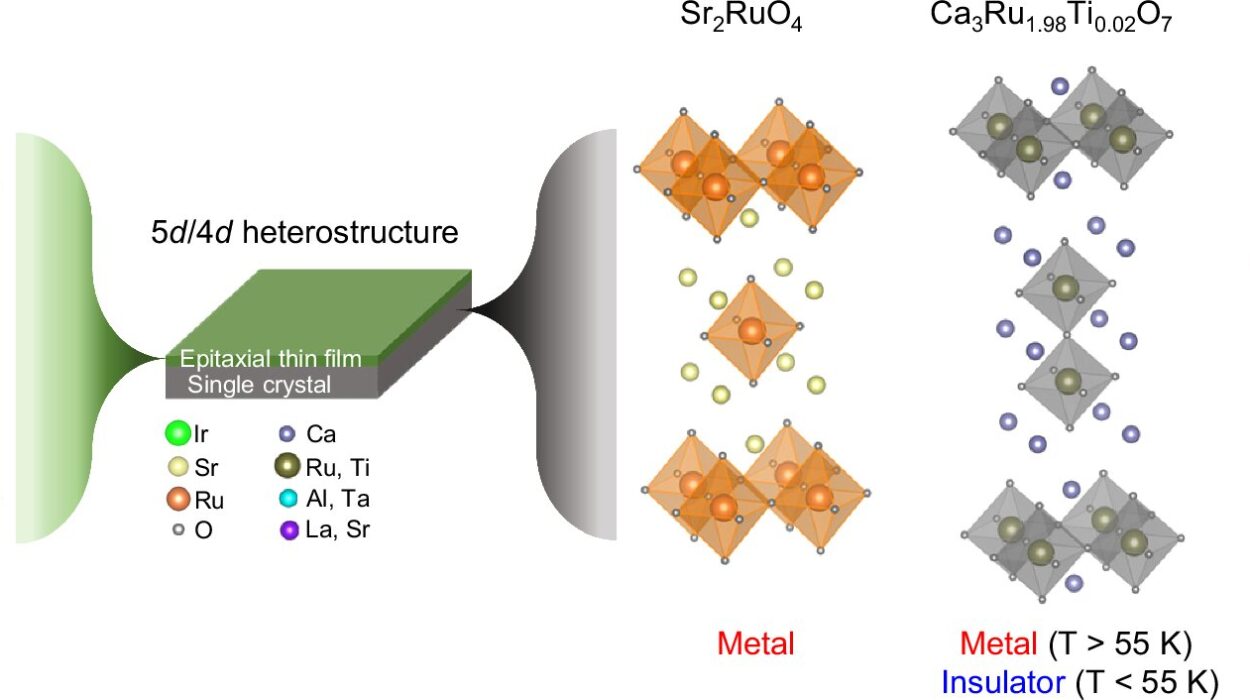

Much of the earlier work on topological defects focused on fluids—materials that flow and rearrange freely. But living tissues are not always fluid. Muscle, for example, behaves more like a solid. It resists deformation. When forces are applied, it strains rather than flows.

“These tissues often act like solids—they resist forces so the material can’t move freely,” Brauns explains. Instead of flowing away, forces generate internal strains and stresses. Those stresses can feed back into the orientation of the tissue’s structural elements.

Muscle tissue is composed of bundles of long, thread-like cells aligned in organized patterns. But alignment is never perfect. When clusters of fibers become misaligned, topological defects emerge. These imperfections mark points where order breaks down and reorganizes.

The question that drove Brauns and his team was deceptively straightforward: do defects in such active solids behave the same way as they do in active fluids?

The answer, revealed through their new mathematical model, is no.

A Model That Changed the Direction of Motion

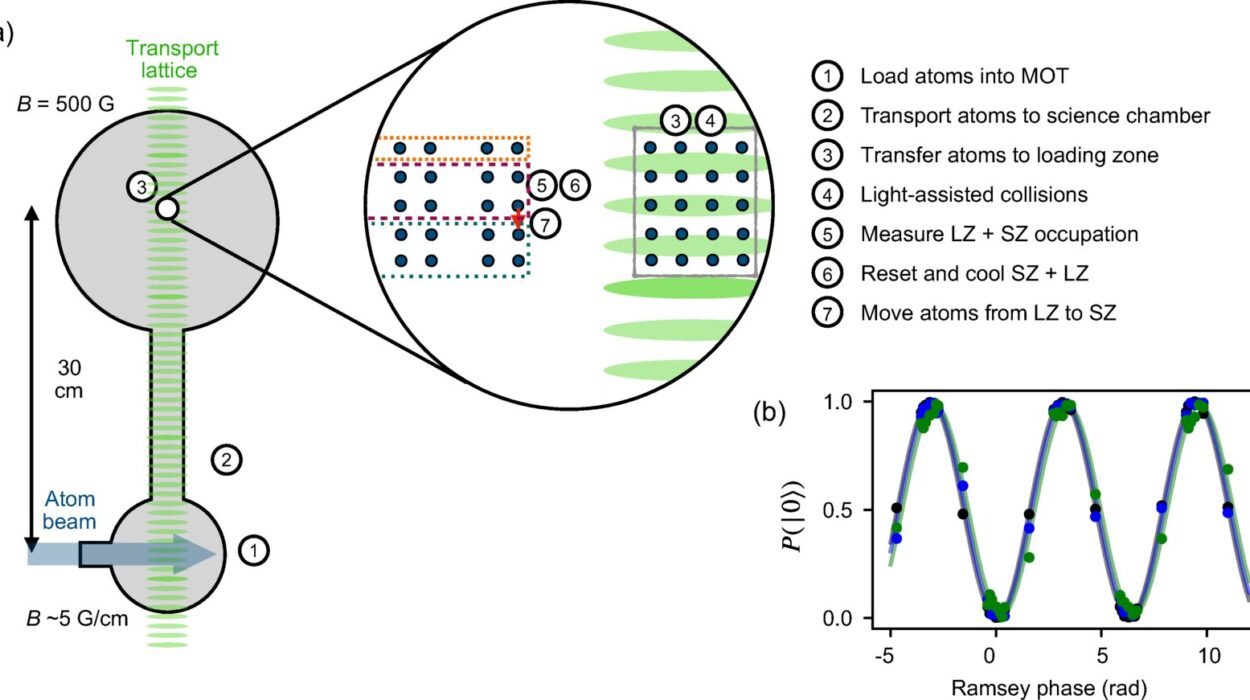

To probe the mechanics of living solids, the team developed a relatively simple model capturing the forces muscles experience as they contract and relax. Rather than attempting to reproduce every biological detail, they focused on the essential physics: how internal activity interacts with solid-like resistance.

What they discovered was striking.

“We show that topological defects in active solids behave fundamentally differently from those in active fluids,” Brauns says. Most notably, they identified a new mechanism for self-propulsion. In active solids, defects can move relative to the surrounding material—but the rules governing their motion are not the same as in fluids.

In fluids, the surrounding material can flow along with a defect, smoothing its path. In solids, however, movement generates internal stress. Those stresses reshape the local orientation of fibers, which in turn alters how the defect moves. The interplay becomes more intricate, more constrained—and sometimes reversed.

The team found that the direction of defect motion in an active solid can be opposite to what fluid-based theories predict. It is as if the imperfection, encountering resistance instead of flow, chooses a different path.

This subtle shift in direction carries profound implications.

The Puzzle of Tissue Formation

Biologists have long been fascinated by morphogenesis, the process by which organisms acquire their shape. From the earliest stages of development, tissues fold, stretch, and reorganize into complex structures. Mechanical forces play a central role, guiding cells into position and coordinating growth.

Topological defects have already been recognized as important players in this process. In the aquatic organism Hydra vulgaris, for example, defects have been linked to the regeneration of body parts. Imperfections in cellular orientation appear to mark locations where new structures form.

But until now, much of the theoretical framework used to interpret these phenomena came from active fluid models. If living tissues behave more like solids, those models may not tell the whole story.

Brauns and his colleagues believe their findings could help resolve lingering mysteries. In laboratory experiments on kidney tissue grown in vitro, researchers observed topological defects moving in the opposite direction from what active fluid theories predicted. The behavior was puzzling, almost contradictory.

“In the active solid case, direction can be reversed compared to an active fluid,” Brauns notes. The new model offers a possible explanation. If kidney tissue behaves as an active solid rather than a fluid, then the observed reversal is not an anomaly—it is expected.

What once seemed like an experimental inconsistency may instead be evidence of deeper physical principles at work.

Imperfections as Architects

There is something poetic about the idea that defects—places where order breaks down—could guide the architecture of life. We often think of perfection as the goal of biological organization. But nature, it seems, relies on controlled imperfection.

In active solids, defects do not merely mark misalignment. They can move, concentrate stress, and influence how tissue reorganizes. As they travel, they reshape their surroundings. And as the surroundings resist and strain, they redirect the defects in return.

This feedback loop between internal activity, mechanical stress, and orientational order creates a dynamic choreography. The tissue is not a static scaffold but a responsive material, constantly negotiating between force and structure.

The new mathematical model does not just describe this dance—it reveals that the choreography changes depending on whether the material flows like a fluid or resists like a solid.

Why This Research Matters

Understanding how tissues acquire and maintain their shape is one of the great challenges of modern biophysics. Morphogenesis is not only central to development but also to regeneration and disease. To grasp it fully, we must understand how forces operate inside living matter.

This study offers a crucial shift in perspective. By distinguishing between active fluids and active solids, it shows that the motion of topological defects—and therefore the distribution of mechanical stress—can differ dramatically depending on the material’s nature. A theory that works beautifully for flowing systems may fail for solid-like tissues.

By providing a framework that accounts for solid behavior, the model opens the door to resolving puzzling experimental results, such as the reversed defect motion observed in kidney tissue. More broadly, it strengthens the bridge between physics and biology, showing how mathematical insights can illuminate the forces shaping living organisms.

In the end, the message is both subtle and profound. Life’s forms are not shaped only by genes or chemical signals. They are sculpted by physics—by the push and pull of internal forces, by the alignment and misalignment of fibers, and by the restless motion of tiny imperfections.

In those imperfections, moving quietly through solid tissue, the blueprint of life may be written.

Study Details

Fridtjof Brauns et al, Active Solids: Topological Defect Self-Propulsion Without Flow, Physical Review Letters (2026). DOI: 10.1103/xv94-xpz2. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2502.11296