Chaos has always been a strange companion to physics. In the classical world, chaotic systems follow precise laws, yet their outcomes quickly become unpredictable. A tiny change in the starting point can ripple outward, erasing any hope of long-term prediction. Quantum theory, with its own counterintuitive rules, promises a deeper language for describing this disorder. But when researchers try to simulate quantum chaos, they run into a wall built not from theory, but from computation.

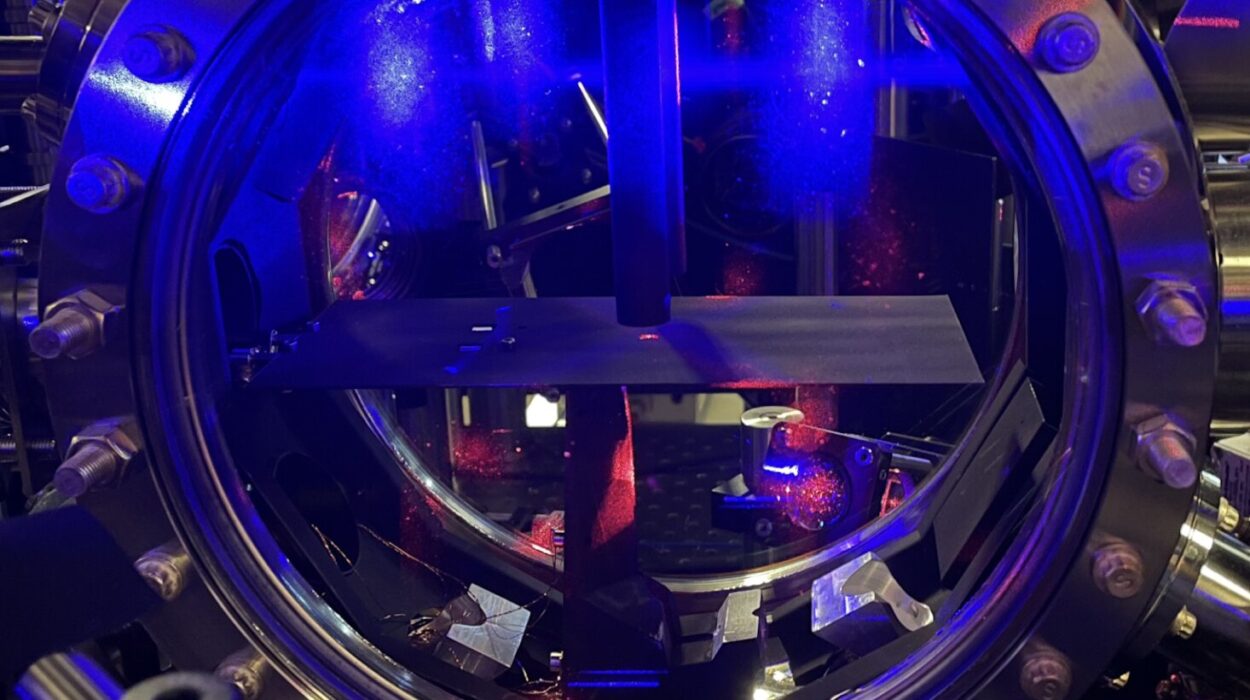

Simulating chaotic quantum systems pushes computers to their limits. The calculations grow so rapidly that even powerful classical machines struggle, and quantum computers themselves are still noisy and imperfect. For years, this tension has shaped what scientists could realistically explore. Now, a team working with a 91-qubit superconducting quantum processor has demonstrated a way forward, revealing that useful insights into quantum chaos may be possible sooner than expected. Their results, published in Nature Physics, suggest that the path to understanding chaos at the quantum level does not have to wait for flawless machines.

A Different Way to Live With Imperfection

The central challenge of quantum simulation is error. Quantum bits are fragile, and interactions with their environment introduce noise that distorts results. The traditional solution is quantum error correction, a method that actively prevents errors by encoding information redundantly across many qubits. While powerful, this approach demands enormous overhead in both qubits and control, far beyond what most current devices can support.

Rather than trying to eliminate errors as they happen, the researchers chose a different philosophy. They embraced error mitigation, a strategy that allows noise to occur but compensates for it afterward. By accepting imperfections during the experiment and correcting their influence in postprocessing, the team conserved valuable quantum resources while still extracting reliable results.

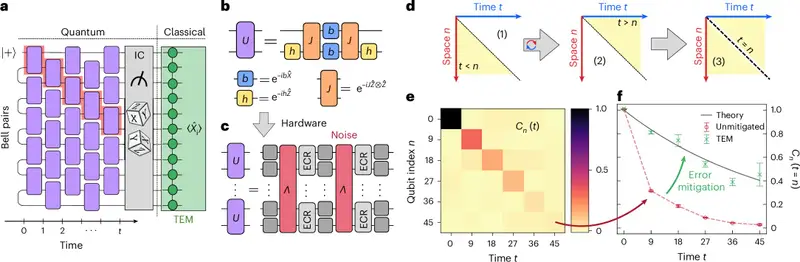

This approach depended on a detailed understanding of the noise affecting the processor. By carefully characterizing how errors accumulated, the researchers applied a recently introduced technique called tensor-network error mitigation (TEM). In this method, errors are mitigated entirely after the experiment through a tensor-network representation of the inverted noisy channel. The trade-off is deliberate: additional classical computation and some approximation bias are exchanged for a reduced sampling burden on the quantum device itself. For a noisy, near-term quantum processor, this balance can make the difference between infeasible and achievable science.

Circuits That Scramble and Still Reveal

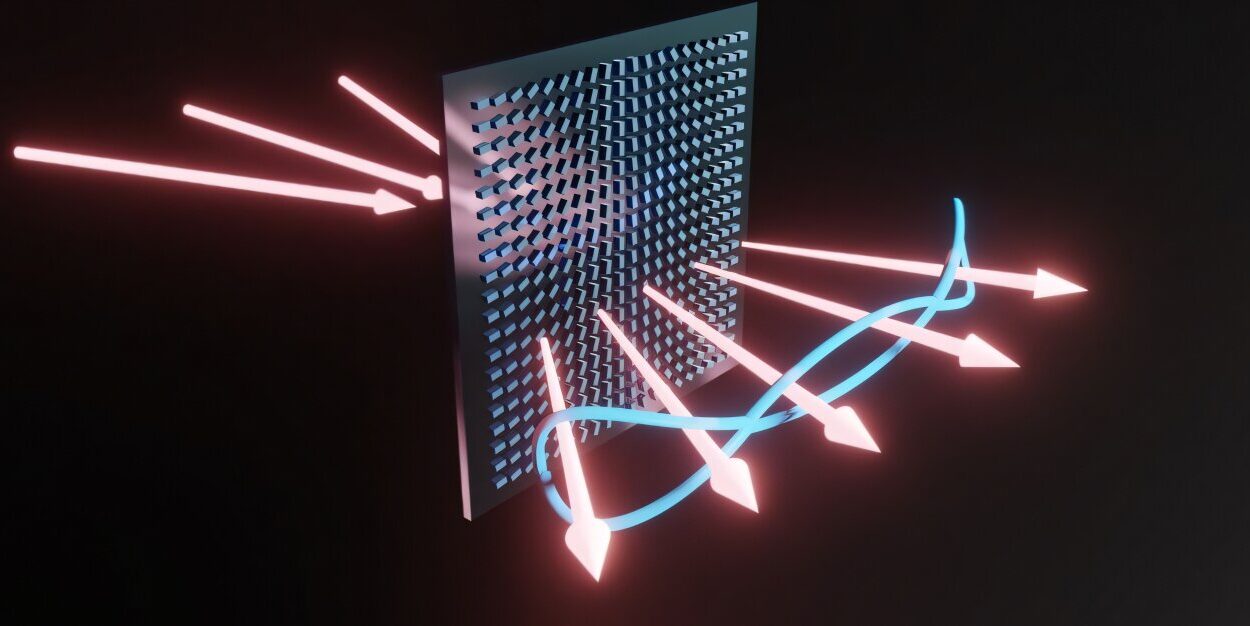

To explore quantum chaos, the team turned to a special class of circuits known as dual-unitary circuits. These circuits are unusual because their quantum gates are unitary in both time and space. In simple terms, they preserve quantum information whether one looks at the system evolving forward in time or spreading across space.

This duality gives them a remarkable property. On one hand, dual-unitary (DU) circuits mix information extremely fast, a hallmark of chaotic behavior. On the other, they allow exact predictions for certain measurements that would normally be inaccessible in highly chaotic systems. This combination makes them a powerful testing ground for studying many-body quantum chaos.

Using DU circuits, the researchers simulated a kicked Ising model, a periodically driven quantum many-body system. They prepared specific initial quantum states and tracked how correlations evolved as the system was repeatedly “kicked” by external driving. In chaotic systems, such correlations typically decay, signaling the loss of memory about the initial state.

With error mitigation applied, the results told a compelling story. The observed decay of autocorrelations closely matched exact analytical predictions for DU circuits across multiple system sizes. This agreement was not limited to small or simplified cases. It extended into regimes where chaotic mixing is strong, suggesting that the quantum processor was capturing genuine many-body chaotic dynamics rather than artifacts of noise.

Testing Against What We Already Know

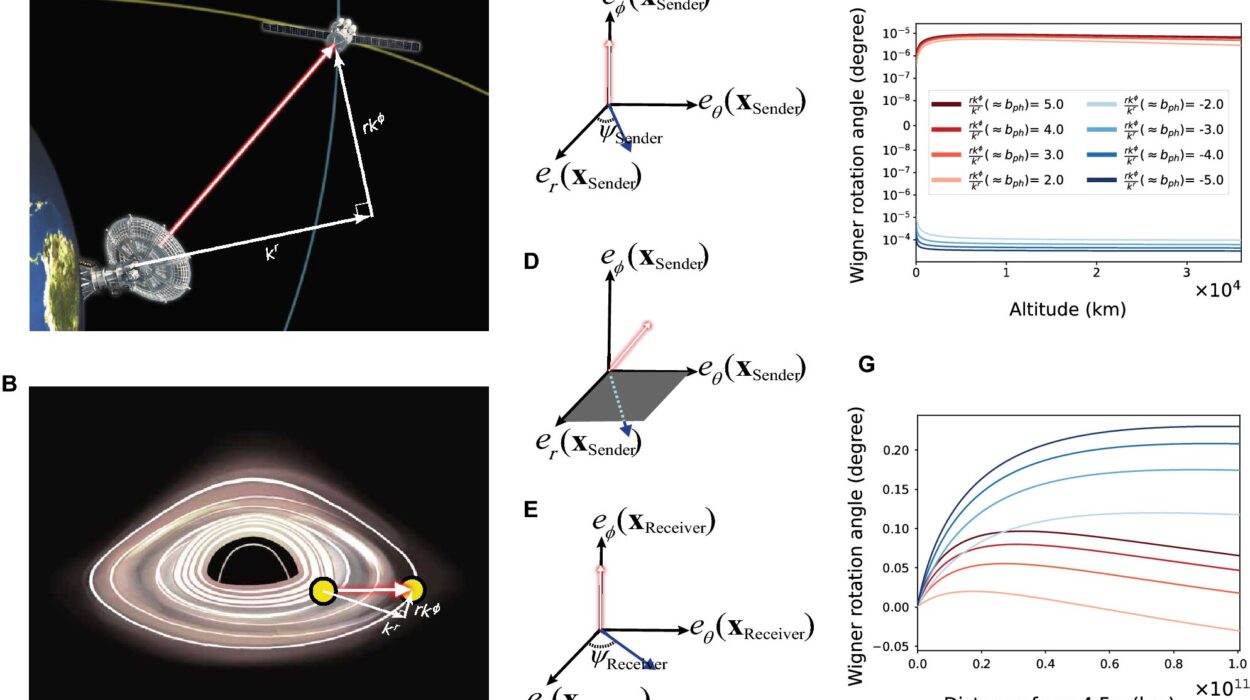

Confidence in a quantum simulation grows when its results can be checked against known solutions. The team benchmarked their experiments in two complementary frameworks, the Heisenberg picture and the Schrödinger picture, each offering a different way to represent quantum dynamics.

For analytically solvable DU circuits, the researchers found that as they moved away from exactly solvable points, the quantum results continued to align with advanced tensor-network classical simulations. This agreement held even at scales where brute-force classical simulation is impossible. In these cases, the quantum processor and classical tensor-network methods converged on the same physical behavior, reinforcing the validity of both approaches.

Beyond the reach of brute-force classical methods and without exact analytical solutions, comparisons became more subtle. The quantum simulations could only be tested against approximate classical techniques. Still, the patterns were revealing. Across a range of parameters, the experimentally obtained data showed strong agreement with simulations carried out in the Heisenberg picture, with deviations appearing only as circuit volumes grew large. In contrast, simulations performed in the Schrödinger picture diverged significantly from the experimental results.

The difference was not merely technical. The researchers noted that Heisenberg-picture simulations converge more efficiently on classical computers, while Schrödinger-picture simulations with comparable convergence quickly become unaffordable at the scale of the experiments. This contrast highlights how the choice of representation can determine whether a problem remains tractable or slips beyond reach.

Where Classical Limits Begin to Show

One of the most striking implications of the work lies in what it reveals about the boundary between classical and quantum computation. In regimes where exact solutions exist, classical and quantum approaches can still meet on common ground. But as systems grow and chaos intensifies, classical methods rely increasingly on approximations that may fail to capture the full dynamics.

The experiments demonstrated that error-mitigated quantum simulations can access regimes where classical brute-force calculations are no longer possible. Even when classical tensor-network methods offer approximate answers, the quantum processor provides an independent route to the physics, grounded in the actual dynamics of a many-body quantum system.

This does not mean that quantum computers have already surpassed classical ones across the board. Instead, it shows that carefully designed experiments, combined with sophisticated error mitigation, can extract meaningful information from noisy hardware. The result is a growing overlap where quantum devices begin to complement classical simulations, especially in the study of complex, chaotic behavior.

Why This Research Matters

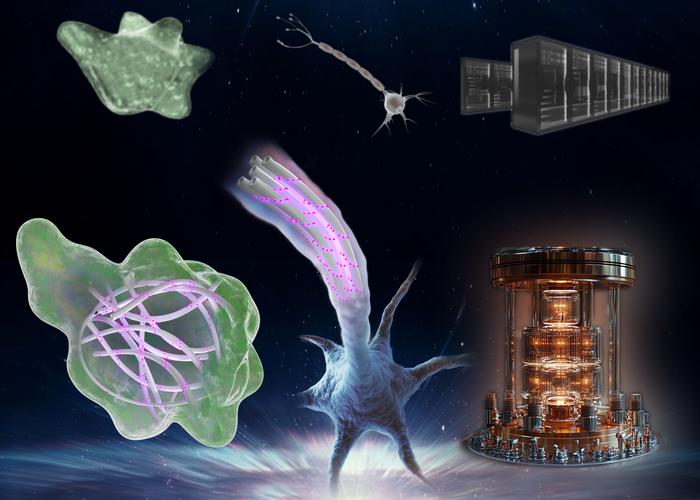

Quantum chaos is more than an abstract curiosity. It underlies how information spreads in quantum systems, how materials transport energy, and how localization emerges or breaks down in many-body dynamics. Understanding these processes is essential for fields ranging from condensed matter physics to the foundations of quantum statistical mechanics.

This work offers a practical pathway toward that understanding. By demonstrating that near-term quantum computers can simulate many-body quantum chaos using error mitigation rather than full error correction, the researchers show that valuable science does not have to wait for fault-tolerant hardware. Their approach builds trust in quantum computing as a scientific tool, proving that noisy devices can still deliver reliable insights when paired with careful noise characterization and postprocessing.

Perhaps most importantly, the study suggests a future in which quantum simulations begin to surpass classical methods before quantum computers achieve full fault tolerance. As hardware continues to advance, the combination of specialized circuits, analytical benchmarks, and error mitigation could open the door to exploring dynamics that have long remained out of reach. In the delicate dance between order and chaos, this work shows that even imperfect instruments can reveal profound patterns when used with precision and imagination.

Study Details

Laurin E. Fischer et al, Dynamical simulations of many-body quantum chaos on a quantum computer, Nature Physics (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41567-025-03144-9. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2411.00765