Sixty-six million years ago, Earth stepped into a world far warmer than the one we know. The Paleogene Period opened with the disappearance of the dinosaurs and unfolded under skies heavy with carbon dioxide, at levels two to four times higher than today. To understand what such heat does to a planet, scientists have learned to listen closely to the whispers left behind in stone, soil, and leaves. In new research led by the University of Utah and the Colorado School of Mines, those whispers tell a surprising story about rain.

The question driving the work seems simple: when the world heats up, where does the water go? For years, a tidy idea has shaped expectations. Warm the planet, and wet places should grow wetter while dry places dry out even more. The physics behind that assumption are solid. But the ancient Earth had other plans.

By reconstructing rainfall during the early Paleogene, researchers uncovered a climate that broke the rules. Even regions far from the poles, places we might expect to thrive on warmth and moisture, often became drier. Not because rain vanished entirely, but because it arrived in unpredictable bursts, separated by long, thirsty pauses.

A Climate That Refused to Behave

Thomas Reichler, a professor of atmospheric sciences and co-author of the study, admits the findings were unexpected. There are, as he says, “good reasons” to believe warming should intensify rainfall in already wet regions. Yet the evidence from deep time tells a different tale. During extreme warming, mid-latitude regions did not reliably grow greener. Many instead faced conditions hostile to vegetation.

The key lies not in how much rain fell each year, but in when it fell. Rain became irregular, sometimes vanishing for extended stretches and then returning in sudden, powerful downpours. In a strongly monsoonal climate, such swings can be devastating. Long dry spells stress plants and soils, while intense rains can overwhelm landscapes, rushing past before ecosystems can absorb the water.

Under these conditions, even places that receive substantial annual rainfall can behave like deserts for much of the year. Life depends not just on totals, but on timing.

Rain That Came All at Once

Rather than tallying yearly precipitation, Reichler’s team focused on variability. Their analysis suggests that during the Paleogene, rainfall was far less regular than today. Gentle, steady drizzle gave way to extremes. Torrents arrived suddenly, then disappeared, leaving behind prolonged drought.

This pattern reshaped the planet unevenly. According to the study, polar regions during this hot era were surprisingly wet, even experiencing monsoonal conditions. In contrast, many continental interiors and mid-latitude zones became drier overall. The rain still came, but it came wrong.

These conclusions come from a broad synthesis of existing research, brought together in a paper published in Nature Geoscience titled “More intermittent mid-latitude precipitation accompanied extreme early Palaeogene warmth.” The work combines geological detective work with climate modeling, a partnership that bridges rocks and equations.

Reading the Language of Stone and Leaves

No one can measure rainfall from millions of years ago. There are no gauges buried in the Paleogene. Instead, scientists rely on proxies, indirect clues preserved in the geological record that reveal how ancient climates behaved.

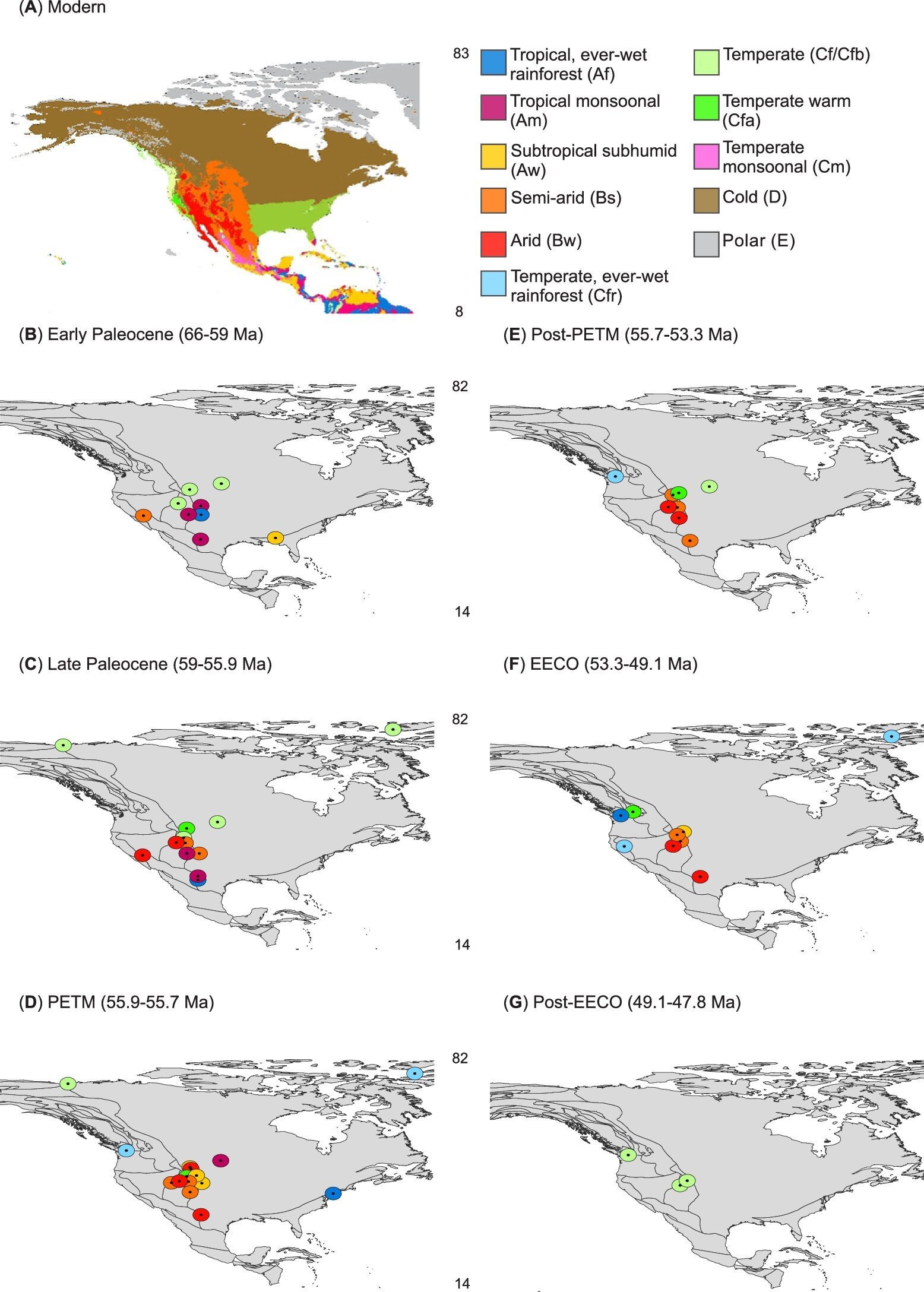

The Colorado School of Mines team focused on plant fossils and ancient soils, while Reichler worked on climate modeling alongside graduate student Daniel Baldassare. Fossilized leaves, for example, carry signatures of the environments in which they grew. Their shapes and sizes mirror those of modern plants living under similar climate conditions.

As Reichler explains, this is not a direct reading of temperature or humidity. It is an informed inference. When a fossil leaf resembles one from a modern wet climate, it hints that moisture once lingered there too. When it does not, the past grows drier.

The land itself also remembers. River deposits and the shape of ancient channels record how water once moved across the surface. Intermittent, powerful rains carve landscapes differently than steady, gentle precipitation. Strong flows scour riverbeds, transport rocks vigorously, and leave behind telltale geomorphological patterns.

Together, these proxies form a mosaic. Each piece carries uncertainty, but assembled carefully, they reveal the best available picture of rainfall under extreme warmth.

A World Forged in Heat

The early Paleogene, spanning roughly 66 to 48 million years ago, represents the warmest chapter in Earth’s history. It began amid catastrophe, with the sudden end of the dinosaurs, and became a cradle for the rise of mammals. It was also a time when iconic landscapes began to take shape. The sediments that would one day form the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon and the badlands of the Uinta Basin were laid down during this restless era.

Warming intensified toward a dramatic peak known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM. During this event, temperatures soared to levels 18 degrees Celsius warmer than those just before humans began releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Some scientists view this moment as a possible worst-case scenario for future climate change.

What makes the new study especially striking is that the irregular rainfall patterns did not appear only at the PETM’s peak. They began millions of years earlier and persisted long after the event had passed. Once Earth’s climate system crossed certain thresholds, rainfall behavior shifted and stayed altered.

Models That Miss the Messiness

One of the most important outcomes of this research lies in its implications for modern climate science. By comparing proxy-based reconstructions with paleoclimate model simulations, the team found that today’s models may underestimate how erratic rainfall can become under extreme warming.

Models are powerful tools, but they are built and tested largely on present-day conditions. Ancient climates provide rare stress tests, revealing how the system behaves when pushed far beyond modern experience. In this case, the past suggests that warming does not simply amplify existing patterns. It can rearrange them.

The dry conditions documented in the Paleogene were often not caused by a drop in total rainfall. Instead, wet seasons grew shorter, and the gaps between rain events lengthened. From an ecological perspective, that distinction matters enormously.

Plants, animals, and entire ecosystems depend on reliability. Water that arrives too late, too fast, or too unpredictably can be almost as damaging as water that never arrives at all.

Why Timing Can Matter More Than Totals

The story emerging from the Paleogene is not one of uniform drought or endless deluge. It is a story of instability. Rainfall became something you could not count on. For landscapes, that meant increased erosion during downpours and prolonged stress during dry spells. For vegetation, it meant living on the edge, unsure whether the next rain would nourish or destroy.

Reichler emphasizes that these findings remind us to look beyond averages. Annual totals can hide dangerous extremes. A year with “normal” rainfall may still include months of drought punctuated by floods. From the perspective of life and land management, those extremes are what matter most.

Why This Ancient Story Matters Now

Understanding Earth’s ancient climates gives scientists a crucial lens for evaluating the future. The Paleogene shows that when the planet becomes very hot, rainfall does not simply follow familiar rules. Variability increases, reliability decreases, and regions that seem safely wet can struggle.

For a warming world, this insight carries weight. Ecosystems, floods, droughts, and water management are all shaped not just by how much rain falls, but by how it is distributed through time. The past suggests that extreme warming can push climate systems into new modes, where surprises become the norm.

By listening to the proxy-recorded memories of leaves, soils, and rivers, this research reminds us that Earth has been here before. And when it was, rain became erratic, landscapes changed, and life had to adapt. As temperatures rise again, the timing of rain may prove just as critical as the temperature itself.

Study Details

Jacob S. Slawson et al, More intermittent mid-latitude precipitation accompanied extreme early Palaeogene warmth, Nature Geoscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01870-6