Deep inside a laboratory in Dresden, something unexpected began to whisper back to the scientists studying it. The researchers were not blasting materials with powerful lasers or flooding them with energy. Instead, they were listening closely to tiny magnetic vortices, structures so small that they exist on scales invisible to the naked eye. What they heard was not a single clear tone, but a chorus—a finely spaced set of frequencies that had never been seen in this context before.

At first, it made no sense. Magnetic vortices were supposed to respond in familiar, predictable ways. Yet here they were, producing a delicate frequency comb, a pattern that hinted at hidden motion and deeper rules at work. The discovery would eventually reveal a new class of Floquet states, emerging not through brute force, but through a subtle dance of magnetic waves.

Inside the World of Tiny Compass Needles

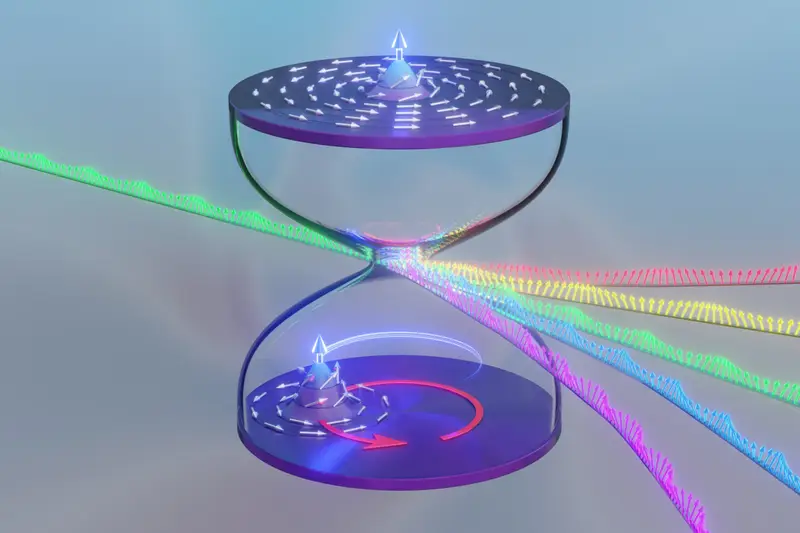

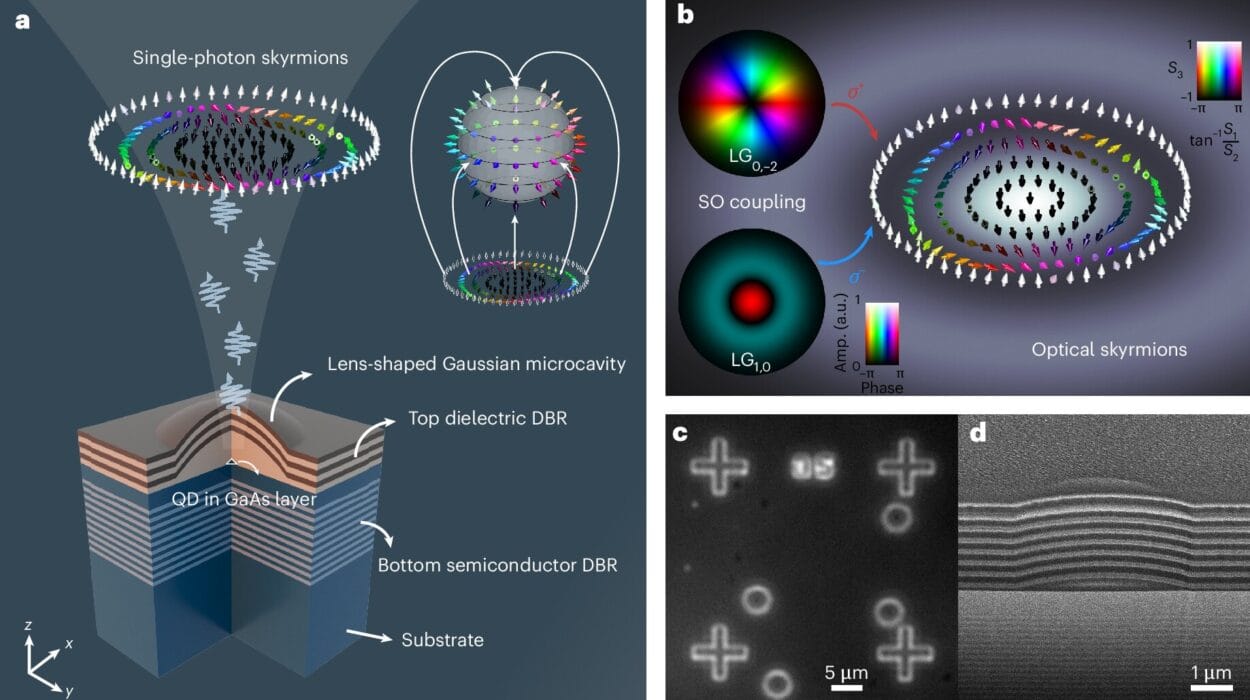

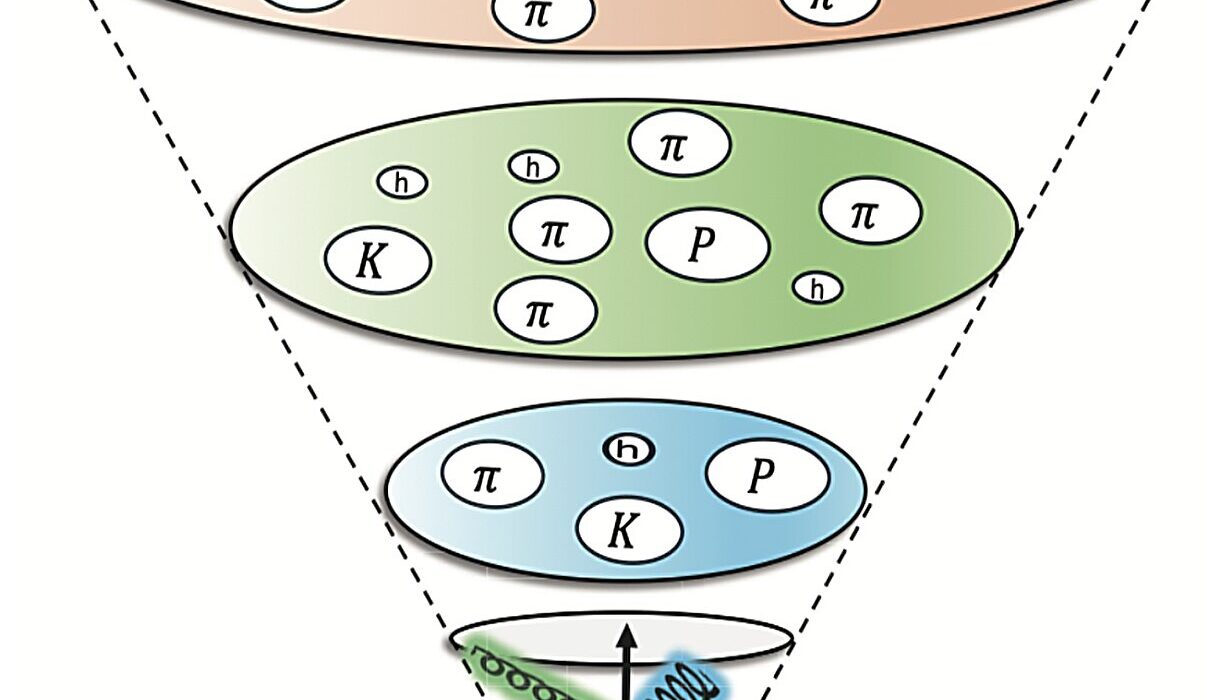

To understand why this was surprising, it helps to picture what these magnetic vortices really are. In ultrathin, micron-sized disks made from materials such as nickel–iron, magnetism does not line up neatly in straight rows. Instead, the elementary magnetic moments—often described as tiny compass needles—curl around a central point, forming a swirling vortex.

This arrangement is stable, elegant, and usually well-behaved. But when disturbed, the system comes alive. A small push can send ripples through the vortex, much like a wave rolling through a stadium crowd. Each magnetic moment tilts just a little, passing its motion along to its neighbors.

Physicists call these collective excitations magnons, and they are more than just curiosities. Magnons can carry information through a magnetic material without moving electric charge, a property that makes them especially attractive for exploring future computing technologies.

A Search for Something Else

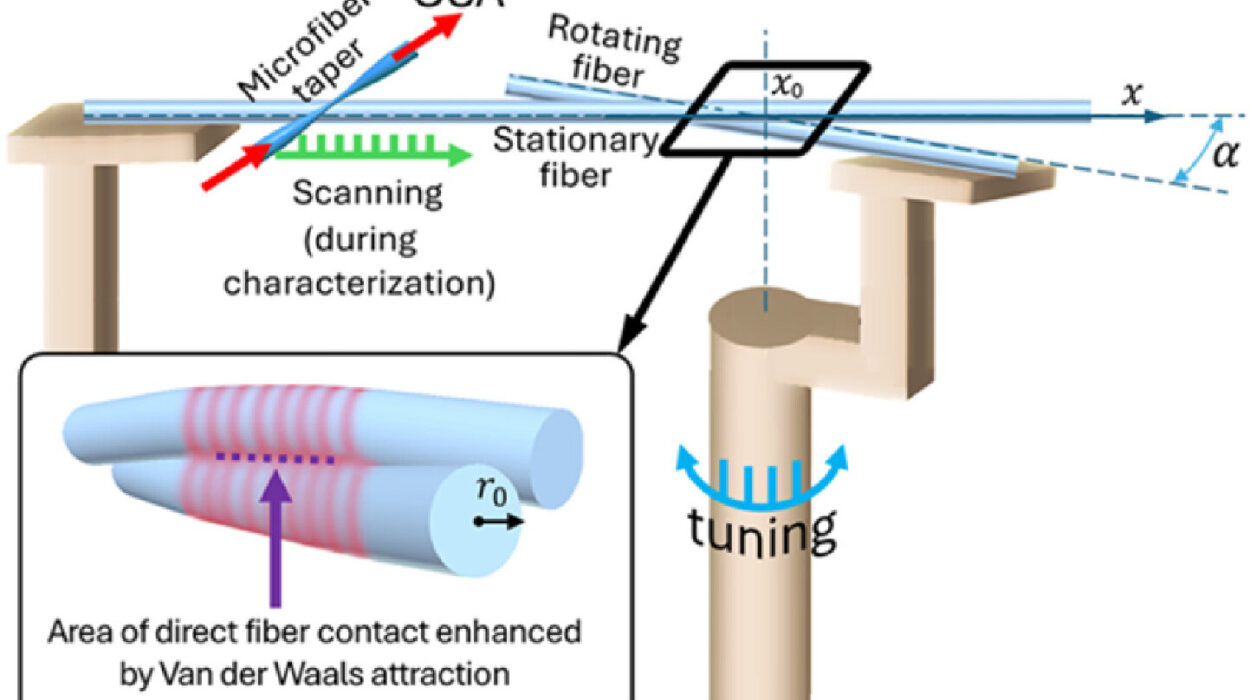

At the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), Dr. Helmut Schultheiß and his team were not originally hunting for new oscillation states. Their focus was on scale. They had begun shrinking their magnetic disks, moving from several micrometers in diameter down to just a few hundred nanometers. The goal was practical and forward-looking: to understand how disks of different sizes might one day be used in neuromorphic computing, a computing approach inspired by the way brains process information.

As the data came in, everything seemed routine—until it didn’t. Some disks behaved differently. Instead of producing a single resonance line when excited, they displayed an entire series of finely split lines. The pattern looked deliberate, structured, almost musical.

“At first we assumed it was a measurement artifact,” Schultheiß recalls. Interference, noise, a glitch in the setup—these were the usual suspects. But repetition brought the same result. Again and again, the frequency comb returned. The message was clear. This was not an error. This was something new.

When Mathematics Steps Out of History

The explanation for the phenomenon led the team back more than a century, to the work of the French mathematician Gaston Floquet. In the late nineteenth century, Floquet showed that systems driven periodically—nudged again and again in a rhythmic way—can develop entirely new states of motion. These Floquet states do not exist in equilibrium. They are born from repetition.

In modern physics, Floquet states are well known, but they usually come at a cost. Creating them has typically required strong laser pulses and significant energy input. The idea that they might emerge quietly, almost on their own, seemed unlikely.

Yet that was exactly what the Dresden team had stumbled upon.

The Subtle Motion at the Core

The key lay in the heart of the vortex itself. When the researchers excited the system strongly enough with magnons, something subtle happened. The magnons began transferring part of their energy to the vortex core, the very center of the swirling magnetic structure.

This transfer did not send the core flying or tear the vortex apart. Instead, it induced a minute circular motion, a gentle orbit around its equilibrium position. That tiny movement was enough to rhythmically modulate the entire magnetic state of the disk.

In effect, the vortex began driving itself periodically. And once that happened, Floquet’s mathematics took over. New oscillation states emerged, neatly spaced in frequency, transforming a single resonance into a full frequency comb.

“We were stunned,” says Schultheiß. The idea that such a small motion—barely detectable—could reshape the entire magnon spectrum was both elegant and profound.

A Symphony Powered by Microwatts

What truly sets this discovery apart is not just what happens, but how little energy it takes. Where other experiments rely on intense laser systems, the Floquet states in these magnetic vortices appear with microwatt-level inputs. That is an astonishing level of efficiency, amounting to only a tiny fraction of the power a smartphone consumes while doing almost nothing at all.

This efficiency changes the conversation. It suggests that complex, controllable oscillation states do not necessarily require extreme conditions. In the right system, with the right internal dynamics, they can emerge naturally.

The frequency comb becomes more than a scientific curiosity. It becomes a tool.

The Idea of a Universal Adapter

One of the most intriguing implications of the work is what Schultheiß calls a “universal adapter.” In today’s technology landscape, different systems often operate at vastly different frequencies. Conventional electronics, magnonic devices, ultrafast terahertz phenomena, and quantum components can struggle to communicate with one another.

Frequency combs are uniquely suited to bridge such gaps. By providing a set of evenly spaced frequencies, they can act as intermediaries, synchronizing systems that would otherwise remain incompatible.

“Just as a USB adapter allows devices with different connectors to work together,” Schultheiß explains, “Floquet magnons could bridge frequencies that don’t naturally align.”

In this vision, magnetic vortices become translators, quietly converting motion and information from one domain into another.

Looking Beyond the Vortex

The team’s curiosity has not been satisfied. They are already planning to explore whether the same principle applies to other magnetic structures. If Floquet states can self-emerge in one system with such low energy demands, there is reason to suspect they may appear elsewhere too.

There are also implications for new computing architectures. By enabling controlled coupling between magnonic signals, electronic circuits, and quantum systems, these effects could help lay the groundwork for hybrid technologies that combine the strengths of each domain.

Behind the scenes, the work was supported by the Labmule program developed at HZDR, which automated measurements and data evaluation across the experiments. This quiet assistant ensured that what the researchers saw was real, repeatable, and robust.

Why This Discovery Matters

At its core, this research changes how scientists think about control and complexity in magnetic systems. It shows that Floquet states do not always require brute-force methods to appear. Sometimes, they can arise from the system’s own internal rhythms, guided by a gentle push rather than a violent shove.

On a fundamental level, the work opens new questions about magnetism, non-equilibrium physics, and the hidden behaviors that can emerge when waves and structures interact. On a practical level, it points toward technologies that are more efficient, more adaptable, and more connected.

By revealing that a whisper of energy can unlock an entire spectrum of new states, the researchers in Dresden have shown that the future of advanced technology may not be loud or power-hungry. It may be subtle, precise, and quietly revolutionary.

Study Details

Christopher Heins et al, Self-induced Floquet magnons in magnetic vortices, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.adq9891. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adq9891