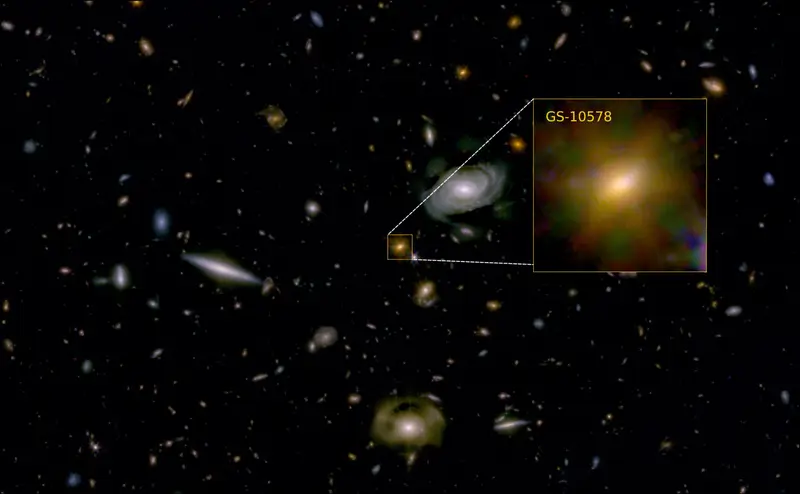

In the vast, early universe, just a few billion years after everything began, one galaxy lived an intense and surprisingly short life. Astronomers now call it GS-10578, though many prefer its warmer nickname, “Pablo’s galaxy.” What they have learned from it is quietly reshaping how scientists think galaxies die.

This galaxy is not a shattered ruin or a violent wreck. It is calm, massive, and orderly. And yet, long ago, it stopped making stars almost entirely. Using observations from the James Webb Space Telescope and ALMA, researchers have uncovered a story not of sudden destruction, but of slow, relentless starvation.

Meeting Pablo’s Galaxy in the Early Cosmos

Pablo’s galaxy existed about three billion years after the Big Bang, a time when the universe was still young and energetic. Despite its age, it had already grown enormous, reaching about 200 billion times the mass of the Sun. Most of its stars formed early, between 12.5 and 11.5 billion years ago, in a rapid burst of creation.

Then something changed. Star birth slowed, faltered, and finally stopped. By the time astronomers observed it, the galaxy had been quiet for about 400 million years, an unusually long silence for such an early era of cosmic history.

The Mystery of Missing Fuel

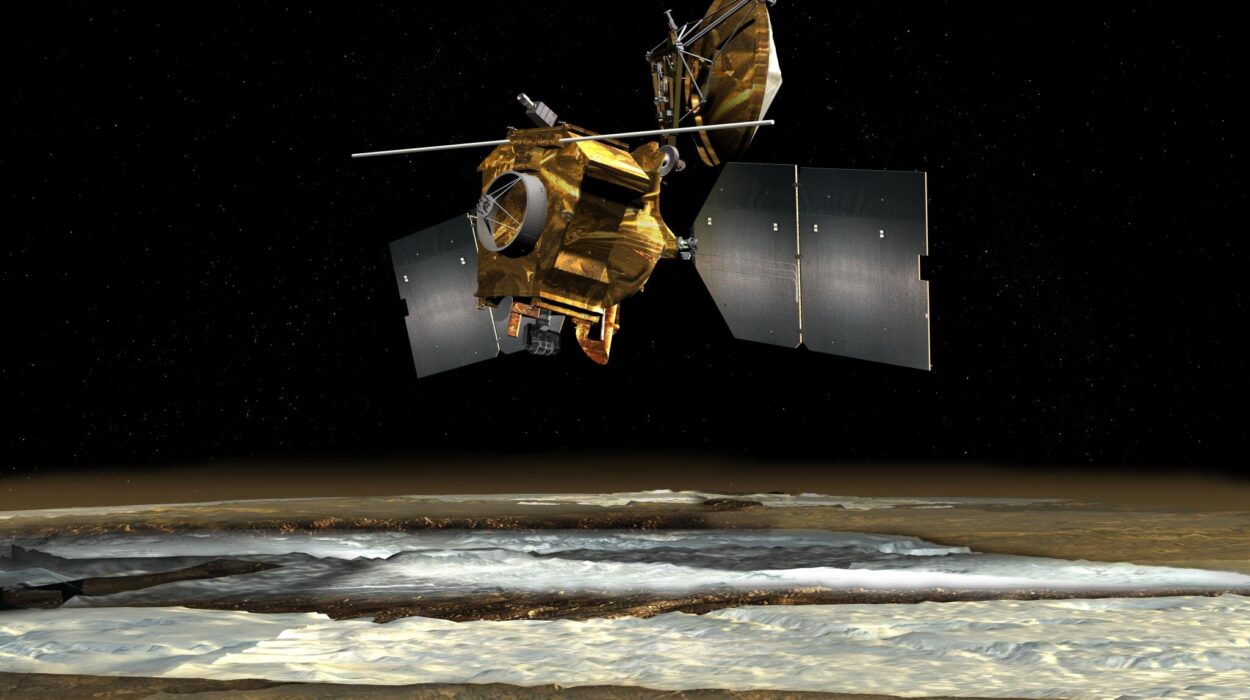

Stars need fuel to form. That fuel is cold gas, especially hydrogen, which gathers, cools, and collapses under gravity. To find out why Pablo’s galaxy stopped forming stars, the research team turned to ALMA, one of the most powerful radio observatories on Earth.

They spent nearly seven hours staring at the galaxy, searching for carbon monoxide, a reliable tracer of cold hydrogen gas. What they found was unexpected.

They found nothing.

There was essentially no cold gas left.

As co-first author Dr. Jan Scholtz explained, the absence itself became the most important clue. Even with one of the deepest ALMA observations ever made of this type of galaxy, the fuel for star formation was simply gone. The galaxy had not been blown apart. It had been slowly drained.

A Black Hole That Didn’t Explode, But Endured

At the center of Pablo’s galaxy sits a supermassive black hole, a familiar suspect in stories of galactic destruction. Often, such black holes shut down star formation through violent outbursts, blasting gas away in a single catastrophic episode.

That is not what happened here.

Instead, the black hole seems to have acted patiently, repeatedly heating the gas in and around the galaxy. Each episode made it harder for fresh material to cool and settle. Over time, the galaxy was cut off from its supply, suffering what researchers described as “death by a thousand cuts.”

Rather than ripping the galaxy apart, the black hole slowly starved it.

Winds That Whispered, Not Roared

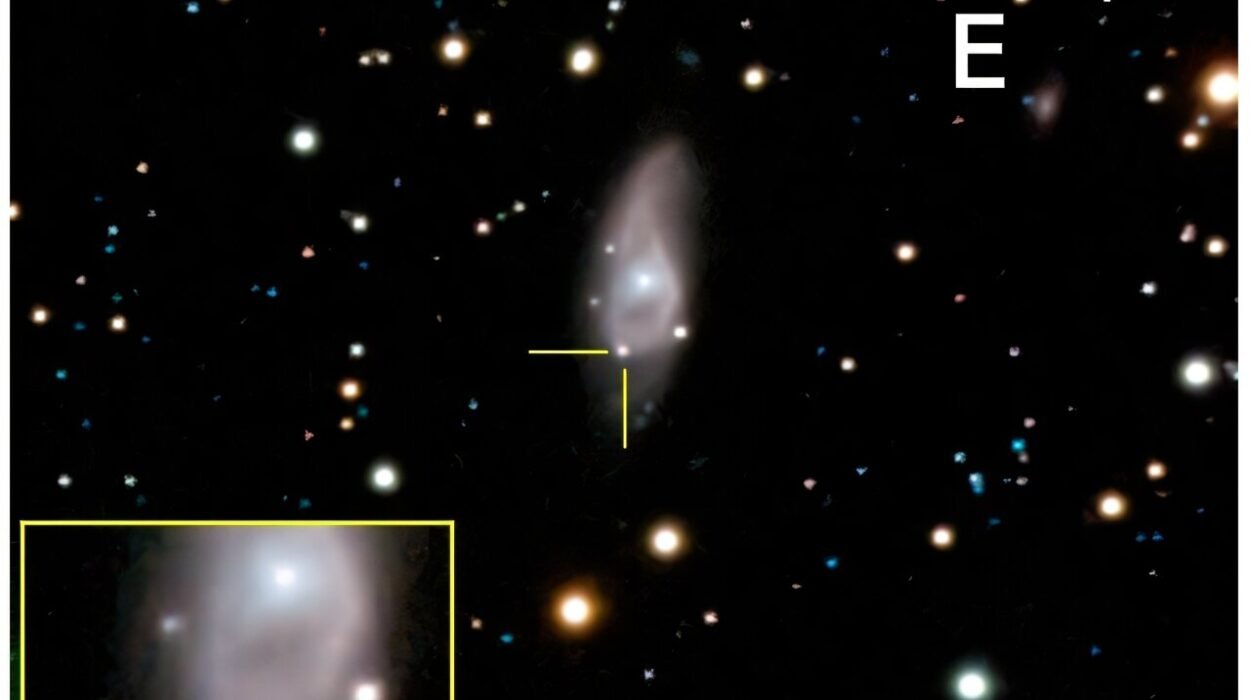

While ALMA saw nothing, JWST spectroscopy revealed something dramatic but controlled. Powerful winds of neutral gas were streaming outward from the black hole at about 400 kilometers per second. These winds were carrying away roughly 60 solar masses of gas every year.

At that rate, the galaxy’s remaining fuel could be exhausted in as little as 16 to 220 million years, far faster than the billion-year timescale usually seen in similar galaxies.

Yet the galaxy itself remained calm. Its stars formed a rotating disk, undisturbed and orderly. This told researchers something crucial.

A Calm Galaxy With a Troubled Heart

As co-first author Dr. Francesco D’Eugenio noted, the galaxy shows no signs of a major collision or merger. There was no dramatic crash with another galaxy to explain its shutdown. The structure remained intact, rotating smoothly through space.

This detail changed everything. If the galaxy had not been violently disrupted, then the current activity of the black hole could not be the single cause of its earlier shutdown. Instead, the evidence pointed to repeated cycles of black hole activity over time.

Each cycle reheated or expelled incoming gas just enough to keep it from settling. Fresh fuel never stayed long enough to restart star formation.

Reconstructing a Life That Ran Out of Time

By tracing the galaxy’s star-formation history, the team reached a striking conclusion. Pablo’s galaxy experienced net-zero inflow. Gas never truly replenished its reserves. The galaxy’s tank was never refilled.

This was not a story of one dramatic ending, but of many quiet interruptions. The black hole did not need to destroy the galaxy. It only needed to prevent renewal.

As Scholtz put it, “You don’t need a single cataclysm to stop a galaxy forming stars, just keep the fresh fuel from coming in.”

A New Explanation for Ancient Galaxies

Pablo’s galaxy is not alone. Since the launch of Webb, astronomers have found a growing number of massive, surprisingly old-looking galaxies in the early universe. Before Webb, such galaxies were virtually unknown.

Now they are appearing more often than expected.

The slow starvation seen in Pablo’s galaxy offers a compelling explanation. These galaxies may have lived fast, forming stars at breakneck speed, only to die young when their central black holes quietly cut off their supply.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research changes how astronomers think about galaxy evolution in the early universe. It shows that galaxies do not need violent explosions or catastrophic collisions to shut down star formation. Slow, repeated black hole activity can be just as effective, and far more subtle.

By combining ALMA’s deep radio observations with JWST’s infrared spectra, scientists were able to see both what was missing and what was moving. Together, these tools revealed a hidden process that might be common, not rare.

Future observations, including 6.5 additional hours of JWST time using the MIRI instrument, will look for warmer hydrogen gas and explore exactly how black holes block fresh fuel from returning.

Pablo’s galaxy teaches a quiet but powerful lesson. In the universe, endings are not always loud. Sometimes, the most profound transformations happen slowly, invisibly, as the fuel for creation simply never comes back.

Study Details

Measurement of the gas consumption history of a massive quiescent galaxy, Nature Astronomy (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02751-z