In a quiet gallery at the Museum of the Rockies, a skull stares back at visitors from deep time. It once belonged to a massive, duck-billed dinosaur called Edmontosaurus, a plant-eater that roamed ancient Montana at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. But this is no ordinary fossil. Buried in its face, as if frozen in a final moment of violence, lies the broken tooth of a tyrannosaur.

That single tooth, wedged stubbornly in bone for 66 million years, has become the center of a scientific investigation that reads like a prehistoric detective story. Through careful study and collaboration between researchers at Montana State University and the University of Alberta, this fossil has begun to speak.

And what it reveals is both chilling and illuminating.

The Land Where Giants Walked

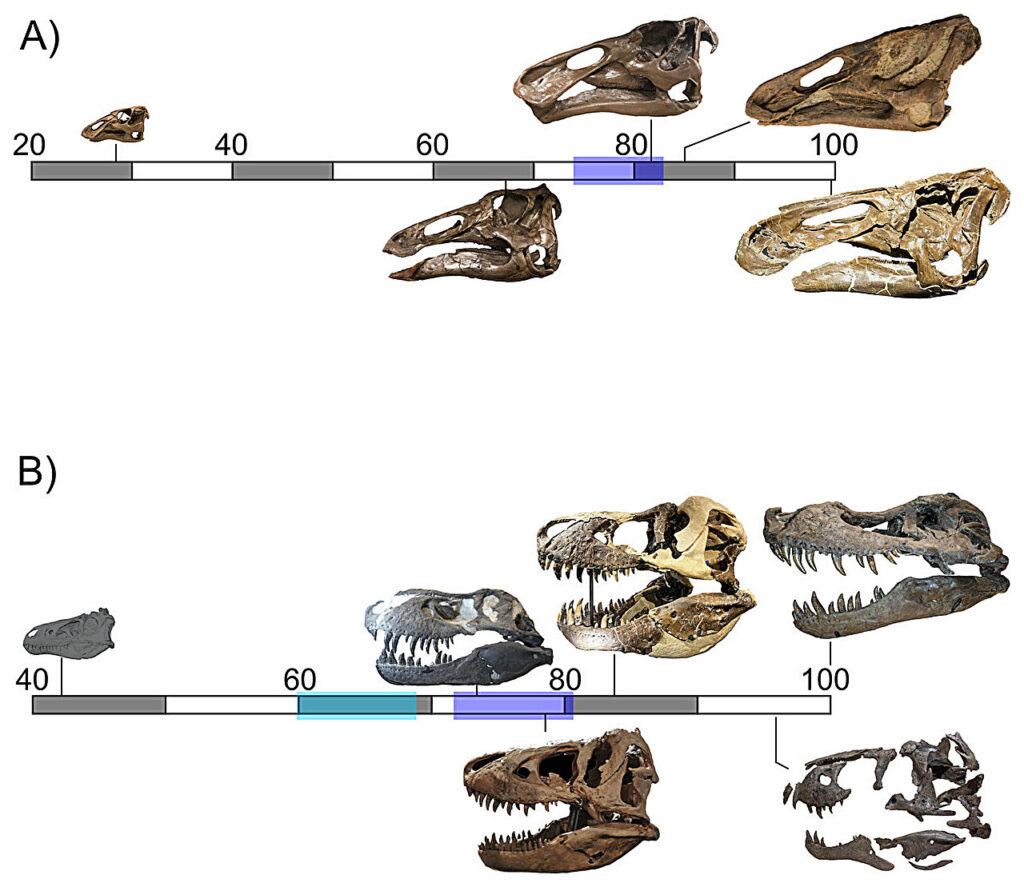

At the close of the Cretaceous period, the region we now call Montana was home to giants. The fearsome Tyrannosaurus, one of the largest meat-eating animals to ever walk Earth, prowled these lands. It shared its world with enormous plant-eaters, including horned dinosaurs like Triceratops and duck-billed herbivores like Edmontosaurus.

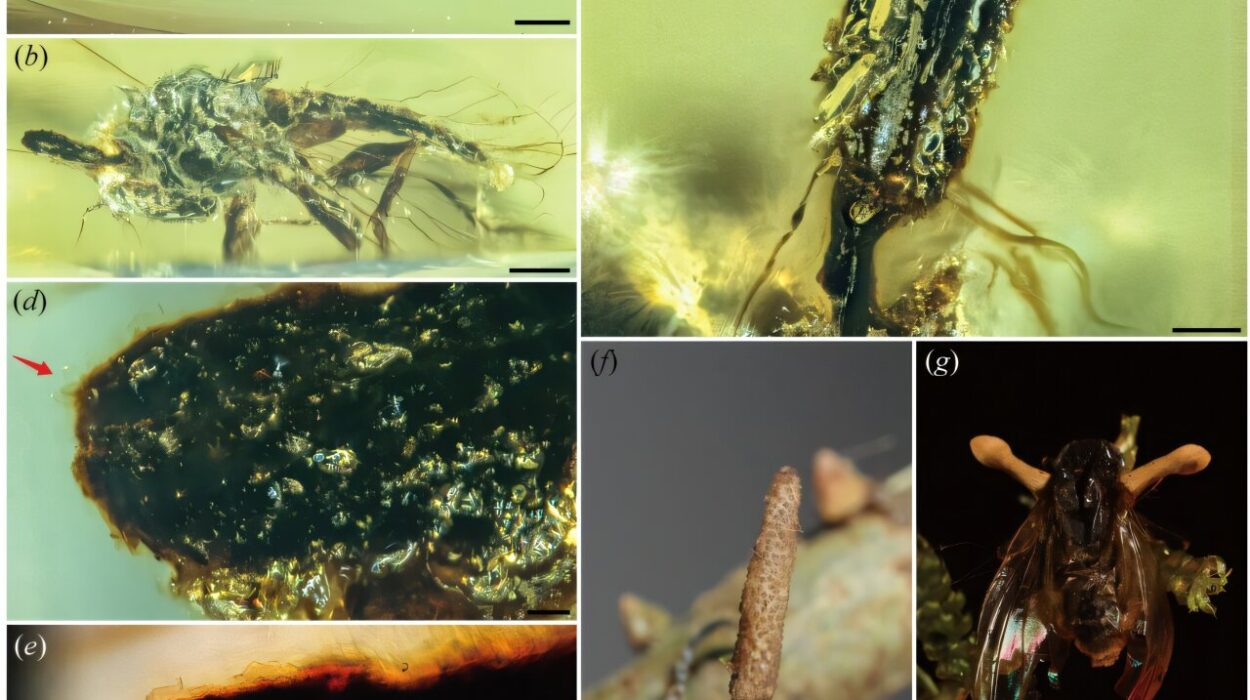

In 2005, on lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management in eastern Montana, paleontologists uncovered a nearly complete Edmontosaurus skull in the Hell Creek Formation. It was an extraordinary find on its own. But nestled inside the fossilized face was something even more extraordinary: a predator’s tooth, broken off and left behind.

The skull eventually found a home in the paleontology collection at the Museum of the Rockies. For years, it carried its secret quietly. Then researchers decided to look closer.

A Rare Clue in a Violent World

Dinosaur bones often bear the scars of ancient encounters. Bite marks are not unusual in fossil collections. But an embedded tooth is something else entirely.

“Although bite marks on bones are relatively common, finding an embedded tooth is extremely rare,” explained Taia Wyenberg-Henzler, a doctoral student from the University of Alberta and one of the study’s lead researchers. A bite mark suggests contact. A broken tooth lodged in bone suggests force, struggle, and a moment of extreme violence.

The tooth offered something precious: identity. It could reveal not only who was bitten, but who did the biting. With that, the researchers began reconstructing the scene, almost like “Cretaceous crime scene investigators.”

Matching the Bite to the Biter

The team compared the embedded tooth to the teeth of all known carnivorous dinosaurs that lived in the Hell Creek Formation. Each predator left behind its own distinctive dental signature. Shape, size, and structure became clues.

The verdict was clear. The tooth most closely matched that of Tyrannosaurus.

To gather more detail, the skull underwent CT scans at Advanced Medical Imaging at Bozeman Health Deaconess Hospital. These scans allowed researchers to peer inside the fossil without damaging it, revealing how deeply the tooth was lodged and how the surrounding bone responded.

What they saw sharpened the story.

Face to Face in the Final Seconds

The tooth was embedded in the nose of the Edmontosaurus. Its angle and placement suggested a face-to-face confrontation.

“Looking at the way the tooth is embedded in the nose of the Edmontosaurus suggests that it met its attacker face-to-face,” Wyenberg-Henzler said. Such positioning is consistent with what happens when a predator delivers a killing bite.

Even more telling was what the skull did not show. There were no signs of healing around the embedded tooth. Bone that survives an injury often begins to repair itself, leaving evidence of recovery. Here, there was nothing. No trace of biological response.

This means one of two things. The Edmontosaurus may have already been dead when the tyrannosaur bit into its face. Or it may have died because of that bite.

Either way, the force was immense. For a tooth to snap off and remain lodged in bone requires significant power. The fracture itself points to what researchers described as deadly force.

For Wyenberg-Henzler, the fossil paints “a terrifying picture of the last moments of this Edmontosaurus.”

Capturing Behavior in Stone

“A fossil like this is extra exciting because it captures a behavior,” said John Scannella, Curator of Paleontology at the Museum of the Rockies. “A tyrannosaur biting into this duckbill’s face.”

Fossils typically preserve bones and shapes. They show us anatomy. But behavior is harder to capture. It disappears quickly after death. Most of the time, scientists must infer how extinct animals acted by studying living species or by interpreting skeletal features.

This skull is different. It freezes a moment of interaction between predator and prey. It is not just a skeleton; it is a snapshot of action.

For decades, scientists have studied and debated the feeding habits of Tyrannosaurus. As one of the largest carnivores to ever walk the planet, how it hunted, killed, and fed has been a topic of ongoing investigation. The embedded tooth offers a rare, direct clue.

Here is physical evidence of a tyrannosaur biting into the face of a large herbivore. Not a scratch. Not a distant mark. A tooth driven so forcefully into bone that it broke and stayed behind.

A Scene Frozen for 66 Million Years

Imagine the moment. An enormous predator confronts a massive herbivore. The ground trembles. Muscles coil. Jaws open wide.

Then, impact.

The tyrannosaur’s teeth sink into bone. One tooth shatters under the strain. The predator pulls back. The broken fragment remains, trapped forever in the skull of its prey.

Time passes. The animals disappear. Sediments bury their remains. Rock forms. Millions of years later, human hands uncover the skull, unaware at first of the story hidden inside.

It is astonishing that such a violent instant could survive across 66 million years. Yet here it is, on display in the museum’s Hall of Horns and Teeth, waiting for curious eyes.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research does more than add a dramatic chapter to dinosaur lore. It strengthens our understanding of Tyrannosaurus behavior using direct physical evidence.

The embedded tooth confirms that Tyrannosaurus bit into the faces of large herbivores like Edmontosaurus. It demonstrates the immense force behind those bites. It shows a probable face-to-face confrontation and suggests either a lethal attack or feeding on a freshly dead animal.

Most importantly, it highlights how rare fossils can move science beyond speculation. Instead of guessing how these animals interacted, researchers can point to a tangible record of that interaction preserved in bone.

The study, published in the journal PeerJ, is the result of collaboration between institutions and the careful use of modern tools like CT scanning. It shows how ancient fossils and modern technology can work together to reconstruct moments from deep time.

Standing before the skull at the Museum of the Rockies, it is impossible not to feel the weight of that moment. The tooth is small compared to the massive bones around it. But it carries enormous meaning.

It reminds us that the Age of Dinosaurs was not just a parade of towering skeletons. It was a living world of tension, hunger, and survival. Predators hunted. Prey resisted. Life ended violently and suddenly.

And sometimes, against all odds, the evidence remains.

In a single broken tooth, we glimpse a flash of prehistoric reality — raw, immediate, and unforgettable.

Study Details

Taia C.A. Wyenberg-Henzler et al, Behavioral implications of an embedded tyrannosaurid tooth and associated tooth marks on an articulated skull of Edmontosaurus from the Hell Creek Formation, Montana, PeerJ (2026). DOI: 10.7717/peerj.20796