Imagine coming face to face with a Triceratops. The first shock might be the horns, the second its immense frill—but lingering behind all of that spectacle is a deeper mystery. Why did this animal carry such an enormous head? And more intriguingly, what was happening inside it?

At the University of Tokyo Museum, Project Research Associate Seishiro Tada found himself staring at that very question. He had long studied the evolution of reptilian heads and noses. Yet the Triceratops skull refused to make sense. Its nose, especially, seemed exaggerated—oversized compared to most animals, ancient or modern. Even knowing the usual anatomical patterns of reptiles, he couldn’t mentally fit the organs inside that vast nasal space.

Something unusual was hiding within the fossilized bone.

Peering Inside Stone

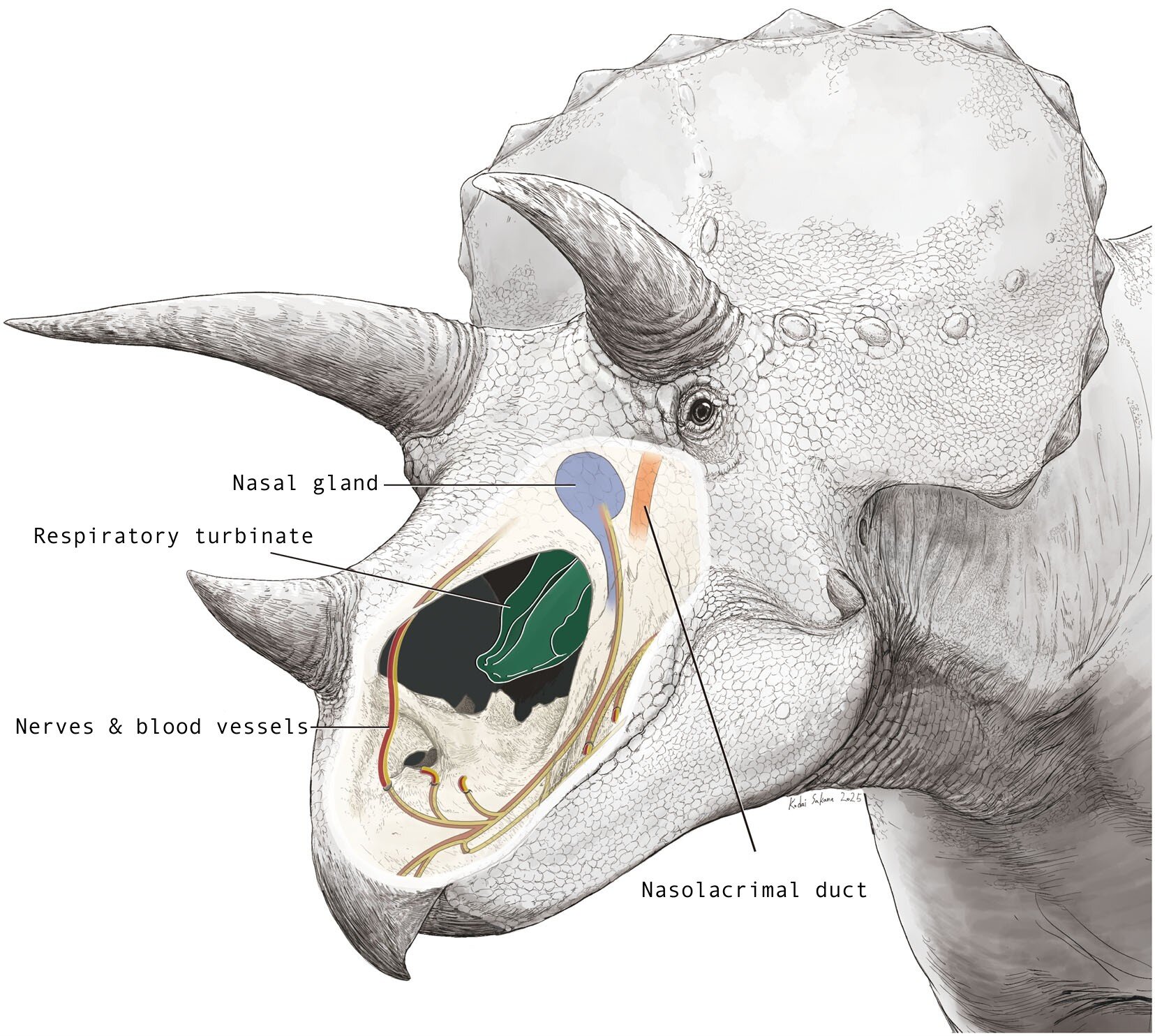

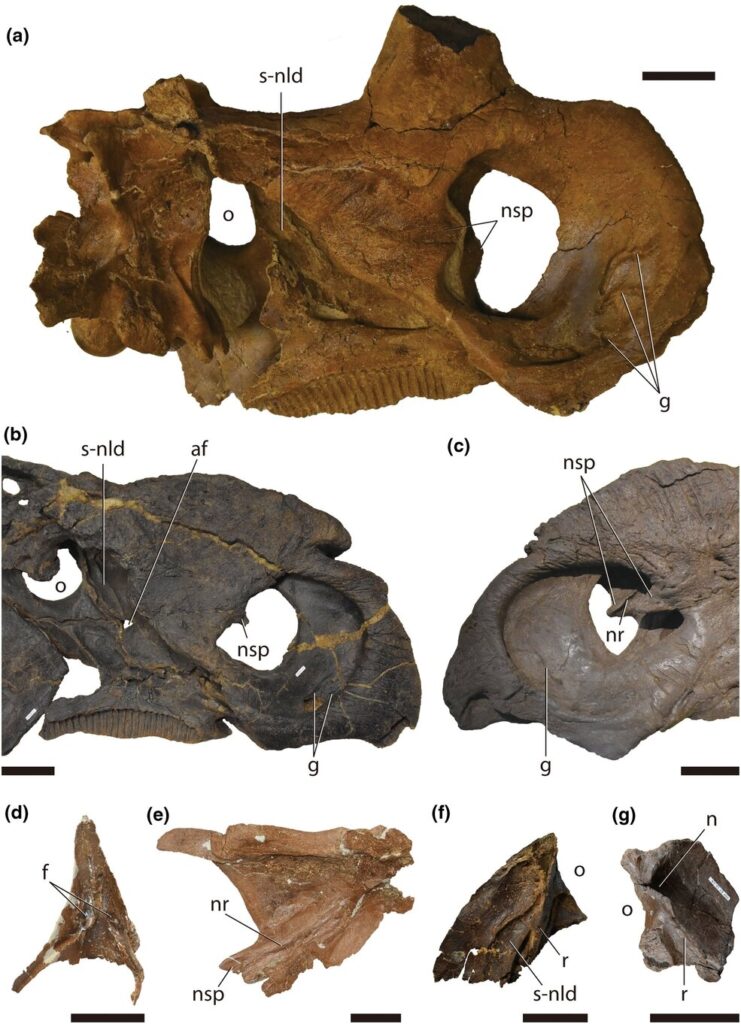

To solve the mystery, Tada and his colleagues turned to X-ray-based CT scans of fossilized Triceratops skulls. These scans allowed them to peer inside the stone without damaging it, revealing internal spaces that had once housed soft tissues—nerves, blood vessels, air passages.

They didn’t stop there. To interpret what they saw, the team compared the fossil structures with modern animals, particularly birds and crocodiles. These living creatures served as anatomical guides. By combining direct observation from the scans with informed inference from modern reptilian snout morphology, the researchers reconstructed how the internal tissues likely fit together.

The result was the first comprehensive hypothesis about the soft-tissue anatomy of horned dinosaurs, known scientifically as Ceratopsia. For a group so visually iconic, their internal anatomy had remained surprisingly obscure. The outside dazzled. The inside was a mystery.

Until now.

The Nose That Rewired Itself

What the team uncovered was not just a large nose—but a nose that had reorganized its internal “wiring.”

In most reptiles, nerves and blood vessels reach the nostrils through routes connecting the jaw and nose. It’s a standard anatomical layout. But Triceratops broke the pattern.

Its skull shape blocked the usual jaw route. As a result, the nerves and blood vessels had to travel through the nasal branch instead. The pathways were rerouted, as if the skull itself had forced anatomy to improvise.

Tada described realizing this while assembling 3D-printed pieces of a Triceratops skull, fitting them together like a puzzle. The moment of recognition came not from a single dramatic discovery, but from patient reconstruction. Piece by piece, the picture became clear. The tissues had evolved in response to the demands of that massive nose.

In essence, the internal anatomy adapted to support the external size. The big nose wasn’t just decorative. It required a fundamental rearrangement of internal structures.

A Hidden Structure With a Familiar Shape

But the most surprising finding lay deeper inside.

Within the reconstructed nasal cavity, the researchers identified evidence of a structure called a respiratory turbinate. These are thin, curled surfaces inside the nose that increase surface area. More surface area means more space for blood and air to exchange heat.

Respiratory turbinates are common in mammals and present in birds. Yet almost no other dinosaurs are known to have possessed them.

The team wasn’t able to observe the soft tissue directly—after all, soft tissue rarely fossilizes. Instead, they looked for structural clues in the bone. In some birds, a ridge in the nasal cavity serves as the attachment base for the respiratory turbinate. Horned dinosaurs, including Triceratops, showed a similar ridge in a similar location.

That similarity led the researchers to conclude that Triceratops likely had a respiratory turbinate as well.

They are careful, however. They’re not “100% sure.” Most other dinosaurs show no evidence for such a feature. But the matching ridge strongly suggests its presence.

And if it was there, it may have played a crucial role.

Cooling a Giant Head

The sheer size of a Triceratops skull posed a physical challenge. Large structures retain heat. Without efficient ways to regulate temperature, overheating becomes a risk.

The researchers believe that the respiratory turbinate may have helped control temperature and moisture inside the nasal passages. Even if Triceratops was not fully warm-blooded, managing heat and humidity would have been important—especially with such a massive skull.

The turbinates, by increasing surface area, would have allowed more effective heat exchange between blood and inhaled air. Moisture could also be regulated as air moved through the curled surfaces.

In other words, the nose wasn’t just for smelling. It may have been a finely tuned environmental control system embedded within bone.

What once looked like an oversized facial feature now appears to have been part of a complex physiological solution.

The Final Piece of a Dinosaur Puzzle

Horned dinosaurs were the last major group whose head soft tissues had not been examined with this kind of anatomical investigation. With this study, published in The Anatomical Record, the team believes they have filled the final piece of a long-standing puzzle.

For decades, the dramatic horns and frills of Ceratopsia captured attention. Artists recreated them. Museums displayed them. Children memorized their names. Yet the internal story—the hidden pathways of nerves, the delicate ridges inside nasal cavities—remained unknown.

Now, thanks to CT imaging, 3D reconstructions, and careful comparison with living animals, we have a clearer vision of what filled that cavernous nose.

And the story may not end there. Tada has already set his sights on other parts of the skull, including the iconic frill. What functions did those dramatic structures serve? What internal adaptations supported them?

The skull still has secrets left to give.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, studying the inside of a fossilized nose might seem like a narrow pursuit. But this research changes how we understand one of the most recognizable dinosaurs in history.

It reveals that external appearance and internal anatomy evolve together. The enormous head of Triceratops wasn’t just a visual spectacle. It demanded internal innovation—rerouted nerves, restructured blood vessels, and possibly the presence of a respiratory turbinate to manage heat and moisture.

This study also demonstrates the power of modern tools like CT scanning to breathe life into stone. By combining imaging technology with comparative anatomy, scientists can reconstruct tissues that vanished millions of years ago.

Most importantly, it reminds us that even the most familiar creatures can surprise us. The Triceratops has stood in museum halls for generations, its massive skull frozen in time. Yet inside that stone, a dynamic story of adaptation and problem-solving was waiting.

The next time we imagine this horned giant roaming ancient landscapes, we might picture more than its horns and frill. We might imagine the air moving through its complex nasal passages, blood exchanging heat along delicate curled surfaces, and nerves tracing newly evolved routes through bone.

A giant head is no longer just a spectacle. It is a testament to evolution’s ingenuity—hidden in plain sight for millions of years.

Study Details

Seishiro Tada et al, Nasal soft‐tissue anatomy of Triceratops and other horned dinosaurs, The Anatomical Record (2026). DOI: 10.1002/ar.70150