In 1969, a fossil was unearthed in southwestern England. It was ancient even then, a silent messenger from roughly 215 million years ago, dating back to the Late Triassic. After its discovery, it was carefully stored away in museum collections, cataloged and preserved. And there it remained—quiet, patient, overlooked—waiting for someone to look closer.

More than half a century later, that moment finally arrived.

What scientists once thought was just another specimen of a known ancient crocodile relative has now been revealed to be something entirely new. The fossil has been named Galahadosuchus jonesi, a new species of crocodylomorph—a distant relative of modern crocodiles and alligators.

But this discovery is not just about ancient bones. It is about reexamining the familiar, about curiosity that refuses to settle, and about the unexpected power of a good teacher.

The Reptilian Greyhound of a Lost World

Imagine the southern United Kingdom as it was 215 million years ago. Not the green hills and coastal towns we know today, but an upland landscape ringed by hot, arid plains. The air would have been different, the vegetation unfamiliar. And moving swiftly through the undergrowth was a creature that looked nothing like today’s heavy-bodied crocodiles.

Galahadosuchus jonesi was slender and long-limbed. Researchers describe it as looking a little like a reptilian greyhound. Unlike modern crocodiles, which are built for powerful aquatic ambush, this animal lived entirely on land. Its elongated, slender limbs suggest speed. It would have stalked small reptiles, amphibians, and early mammals, darting through vegetation with agility.

Its body posture was upright, not sprawled. This detail inspired part of its name. The “Galahad” in Galahadosuchus refers to Galahad, the Arthurian knight renowned for moral uprightness. The animal’s physical stance—its literal uprightness—echoed that legendary figure.

The second part of its name carries a much more personal story.

A Name That Carries Gratitude

The species name jonesi honors David Rhys Jones, a secondary school physics teacher at Ysgol Uwchradd Aberteifi in Cardigan, Wales. He was the teacher of Ewan Bodenham, the Ph.D. student and lead author who helped identify the fossil as a new species.

Bodenham has spoken warmly about his former teacher. He described Mr. Jones as someone who could explain complex ideas clearly, but more importantly, someone who was genuinely interested in science. That enthusiasm mattered. It inspired.

Mr. Jones, Bodenham said, did not let students settle. He challenged them. He pushed them to be their best. And he did so with humor and kindness.

In the careful language of scientific naming, there is rarely room for emotion. Yet here, embedded in the Latinized name of a creature that lived millions of years ago, is a quiet tribute. The discovery was published in the journal The Anatomical Record, but its story stretches far beyond academic pages.

Beneath the Limestone, a Hidden Archive

To understand how this animal was preserved, we have to travel even further back in time.

During the Late Triassic, the region around what is now southern Wales and southwest England was shaped by a limestone karst system. Soft limestone, over long stretches of time, becomes riddled with sinkholes and caves. It is a landscape that can swallow what falls upon it.

These geological features, known as fissure deposits, formed on both sides of the Bristol Channel. Animals that died on the surface were washed into caves and cracks in the limestone. Sediment followed, gradually burying and preserving bones in natural traps.

Over millions of years, these fissures filled with the remains of animals that lived between about 230 and 200 million years ago. The result is a remarkable fossil archive of an ancient ecosystem.

Among these remains are some of the earliest known dinosaurs, including Thecodontosaurus and Pendraig. But dinosaurs were not alone. The fissures also contain a rich assortment of smaller reptiles. There is Cryptovaranoides, thought to be one of the earliest known lizards. There is Threordatoth, described as a horned lizard-like animal. And there is Kuehneosaurus, a gliding reptile.

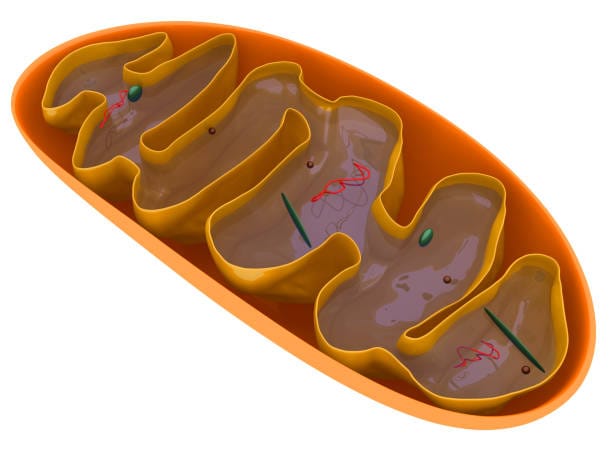

Within this crowded prehistoric community, early relatives of crocodiles were also present. One such animal was Terrestrisuchus, an early member of the group known as Crocodylomorpha. Unlike today’s crocodiles and alligators, these early forms had long, slender legs and lived fully on land.

For years, the fossil that would become Galahadosuchus jonesi was thought to belong to this known species.

The Moment Something Didn’t Fit

The turning point came during a careful reexamination of fossils in museum collections.

As part of his Ph.D. project, Ewan Bodenham was studying the evolutionary relationships of early crocodiles. This required detailed anatomical comparisons between fossils. Each bone, each joint, each ridge and groove had to be carefully described and measured.

When the team looked closely at one particular specimen labeled as Terrestrisuchus, something felt off. It did not quite match the others.

Instead of dismissing the differences as minor variation, they dug deeper. They conducted a detailed anatomical description, comparing the specimen with other early crocodylomorph fossils.

In total, they identified 13 key differences—enough to suggest that this was not simply another example of an existing species. Several of these differences were found in the wrist bones. In this specimen, the wrist bones were shorter and stockier compared to those of known Terrestrisuchus fossils.

These were not trivial variations. They were consistent and distinct enough to justify naming a new species.

What had been quietly resting in a collection for decades was, in fact, something the world had never formally recognized before.

A World on the Edge of Change

The discovery adds another layer to our understanding of life during the Late Triassic, a period just before a dramatic global transformation.

This era preceded the Triassic–Jurassic mass extinction event, a time of sweeping environmental change linked to increased volcanic activity. As volcanic eruptions intensified, the climate and environment shifted dramatically. Many species disappeared, and ecosystems were reshaped.

By documenting which animals lived before this upheaval, scientists can better understand what biodiversity looked like on the brink of disaster. The fissure deposits provide a snapshot of a world just before profound change.

In this snapshot, Galahadosuchus jonesi now takes its rightful place alongside early dinosaurs, gliding reptiles, and some of the earliest lizards.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, the naming of a new species from a decades-old fossil might seem like a small adjustment to the scientific record. But its significance runs deeper.

First, it reveals that museum collections are not static archives. They are living libraries of discovery. Fossils unearthed long ago can still reshape our understanding when examined with fresh questions and sharper focus.

Second, the identification of Galahadosuchus jonesi expands the known diversity of early crocodylomorphs. It shows that even before the mass extinction event at the end of the Triassic, these ancient relatives of crocodiles were already varied in form and anatomy. Diversity was flourishing.

Finally, this research helps scientists reconstruct how ecosystems functioned before one of Earth’s great turning points. By knowing who was there and how they were built, researchers can better explore how species respond to massive environmental change.

And there is one more layer. This discovery carries a human story. It reminds us that science is not only about bones and measurements. It is about mentorship, inspiration, and the quiet encouragement that pushes a student to look closer instead of settling for easy answers.

A fossil waited fifty years in silence. A researcher looked again. A teacher’s influence echoed across millions of years.

In the limestone fissures of southern Britain, an ancient runner has finally been recognized. And in its name, carved into scientific history, lives a tribute to curiosity—and to the people who ignite it.

Study Details

Ewan H. Bodenham et al, A second species of non‐crocodyliform crocodylomorph from the Late Triassic fissure deposits of southwestern UK: Implications for locomotory ecological diversity in Saltoposuchidae, The Anatomical Record (2026). DOI: 10.1002/ar.70162