Beneath the turquoise shimmer off Queensland’s coast, in a place once alive with the riotous colors of coral gardens and darting fish, a silence has settled. The corals of Lizard Island, part of Australia’s treasured Great Barrier Reef, have gone ghostly pale—and now, they are dying at an unprecedented rate.

New research published in the journal Coral Reefs has revealed a grim milestone: an average coral mortality rate of 92% following last year’s catastrophic bleaching event, with some patches experiencing losses as high as 99%. This makes it one of the most severe coral die-offs ever recorded anywhere on Earth.

Even in a reef system battered by decades of warming oceans, storms, and invasive predators, the sheer scale of this loss has stunned scientists. “This marks one of the highest coral mortality rates ever documented globally,” said lead author Dr. Vincent Raoult from Griffith University. “Despite relatively lower heat stress compared to other areas of the Great Barrier Reef, the damage here has been devastating.”

A Graveyard in the Coral Sea

The study focused on Lizard Island, a remote yet scientifically significant coral outcrop located over 1,600 kilometers north of Brisbane. It’s long been a jewel in the crown of coral research—home to the Australian Museum’s research station and the site of some of the most detailed reef monitoring in the world.

The team, comprising researchers from Griffith University, Macquarie University, James Cook University, CSIRO, and drone-mapping specialists GeoNadir, surveyed 20 separate reef patches across both northern and southern zones of Lizard Island. Using high-resolution drone imagery captured during and after the 2024 bleaching event, the scientists documented bleaching of up to 96% of living coral cover in March, with 92% of that coral subsequently perishing by June.

The numbers are not just high—they are haunting.

“Some areas were completely flattened,” said Professor Jane Williamson of Macquarie University, senior author of the study. “You could look across a whole patch of reef and not find a single living coral colony. These are not slow changes. They’re sudden. They’re terminal.”

The Invisible Killer: Heat

At the heart of this unfolding tragedy lies a now-familiar culprit: ocean heatwaves, supercharged by climate change.

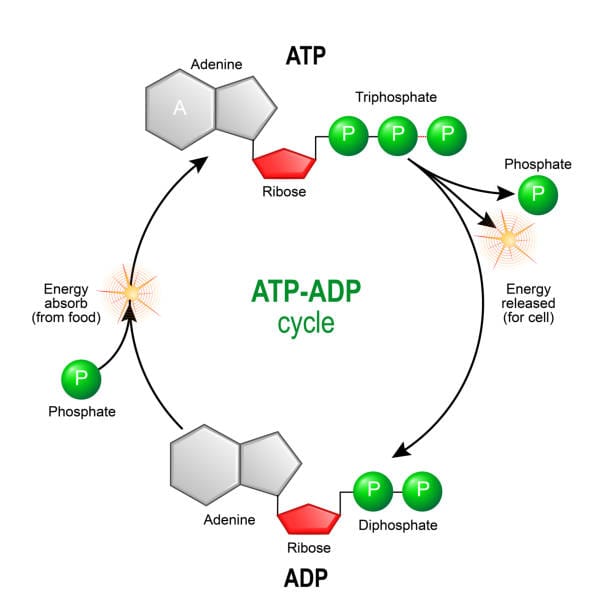

Corals live in a delicate symbiosis with tiny algae called zooxanthellae, which give them both their color and much of their energy. When water temperatures rise too high, this relationship breaks down, and the algae are expelled, leaving the corals white, starving, and exposed. If temperatures don’t return to normal quickly enough, the coral dies.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared a Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event in April 2024, driven by a relentless marine heatwave that spread across tropical oceans. The event reached the Great Barrier Reef with terrifying speed and intensity.

Lizard Island, paradoxically, wasn’t even the hardest hit by heat stress—its waters experienced a cumulative stress of around 6°C-weeks, relatively moderate compared to some central reef regions. Yet mortality rates here were sky-high.

“That’s what makes this finding so disturbing,” said Dr. Raoult. “We would have expected some mortality, but the sheer scale of death at relatively modest heat levels tells us the ecosystem has lost much of its resilience.”

A Legacy of Wounds

The high mortality rates weren’t born in 2024 alone. The reefs around Lizard Island have been enduring body blows for a decade. They suffered back-to-back mass bleaching events in 2016 and 2017, were pummeled by tropical cyclones, and have been repeatedly assaulted by outbreaks of the Crown-of-Thorns starfish, a natural predator whose numbers explode in nutrient-rich, warm conditions.

After a few fragile signs of recovery, many reef areas had started to rebuild by 2022 and 2023—only to be pushed off a cliff by last year’s bleaching.

“Coral ecosystems are like tightrope walkers,” said Professor Williamson. “They can recover if given time and stable conditions. But each hit knocks them off balance. And in this case, it looks like the rope was cut altogether.”

Eyes in the Sky, Feet in the Water

The study’s unique power came from its use of drone-based monitoring, a fast-evolving method that allows researchers to capture massive amounts of visual data across wide reef areas, while still identifying specific coral colonies and bleaching patterns.

Using DJI Mini 3 Pro and Autel Evo II drones, the team surveyed 10-meter-square plots across multiple sites in March 2024, then returned in June to reassess survival rates. Their findings were cross-validated by in-water diving surveys, confirming the grim accuracy of the drone’s eye.

“It’s the first time we’ve had such detailed before-and-after imagery over the same areas during a bleaching event,” said Dr. Raoult. “It doesn’t just tell us what died. It shows us how quickly it happened.”

Drone technology is allowing reef scientists to scale up their efforts, building detailed 3D maps of reef structures, coral types, and damage zones with a precision that would have been impossible just a decade ago.

But what they are seeing more and more, year after year, is loss.

Bleached Beyond Resilience

The implications of this mortality event go beyond one island.

Coral reefs are among the most diverse ecosystems on the planet, home to one-quarter of all marine life, even though they cover less than 1% of the ocean floor. They protect coastlines from erosion, support fishing industries, and attract millions of eco-tourists. When reefs die, entire food webs unravel.

And they are dying more often. Since 2015, more than 75% of the world’s reefs have experienced bleaching-level heat stress. This is no longer a future problem—it is happening now, with increasing intensity and frequency.

“Bleaching is no longer an anomaly. It’s becoming the norm,” said Professor Williamson. “And with each event, the ability of corals to recover diminishes.”

The Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event, in particular, has impacted reefs across all major tropical oceans—from the Pacific to the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea. And the worst may still be to come. Predictions from NOAA and global climate models suggest that even stronger heatwaves could arrive in the next five to ten years.

Hope in the Ashes?

Despite the despair, the scientists are not giving up.

The team at Lizard Island is now undertaking extended monitoring through 2026, backed by a Lizard Island Critical Grant from the Australian Museum. They hope to find signs of reef regeneration, to identify coral species or genetic variants that showed some resistance, and to understand how pockets of survival might serve as seeds for future recovery.

“These ecosystems have amazed us with their capacity to rebound,” said Dr. Raoult. “But there’s a tipping point. We need to know whether Lizard Island crossed it—or whether there’s still a path back.”

Global solutions, however, lie not just in reefs, but in emissions, energy, and political will.

The coral catastrophe unfolding off Australia’s coast is not isolated. It’s the result of carbon pollution warming the oceans, year after year, unchecked. Unless the world cuts greenhouse gas emissions drastically—and soon—the vision of a healthy, colorful reef may vanish entirely within the lifetime of a child born today.

A Warning Written in White

The 2024 coral bleaching event at Lizard Island is not just a science story. It is a warning cry from the ocean.

It tells us that even reefs in relatively cooler regions are no longer safe. That prior damage compounds vulnerability. That coral resilience is faltering under relentless assault. And that technology can show us the truth in terrifying clarity.

But it also tells us something else: that we still have a choice.

We can choose to listen to the science. To shift energy systems. To protect the parts of the reef that remain. To act before the silence beneath the waves becomes total.

As the reef turns white, the question is no longer if we will respond. It is when. And whether we’ll be in time.

Reference: Vincent Raoult et al, Coral bleaching and mass mortality at Lizard Island revealed by drone imagery, Coral Reefs (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s00338-025-02695-w