In the frozen reaches of Antarctica, beneath sheets of drifting sea ice, a curious concert is underway. If you were to dip a hydrophone into the icy waters between October and January, you wouldn’t just hear the creaks and groans of shifting glaciers—you’d hear music. Not classical, not pop, but haunting underwater arias sung by one of the Southern Ocean’s most enigmatic predators: the leopard seal.

Now, a new study published in Scientific Reports by researchers at UNSW Sydney reveals that these solitary marine mammals sing in ways that are surprisingly similar to humans—specifically, to our nursery rhymes. The study has brought the enigmatic songs of leopard seals into the scientific spotlight, uncovering patterns of sound that are not just complex, but uncannily structured.

“We found that leopard seal songs have a surprisingly structured temporal pattern,” says Lucinda Chambers, a Ph.D. candidate at UNSW and the study’s lead author. “When we compared their songs to other vocal animals and types of human music, we found their information entropy—a measure of how predictable or random a sequence is—was remarkably close to our own nursery rhymes.”

In a world where animals are often studied for their physical prowess or hunting techniques, it’s rare to come across a species that wins attention for their musicality. But for leopard seals, it turns out, their survival and social interaction may depend just as much on melody as on muscle.

Serenading the Southern Ocean

Every year, male leopard seals dedicate weeks of their lives to one thing: singing. From late October to early January—Antarctica’s brief spring—they can be found diving beneath the ice and emerging again in rhythmic cycles. For up to 13 hours a day, they alternate two minutes underwater with two minutes above the surface, creating a trance-like cycle of breathing and belting.

“It’s big business for them,” says Professor Tracey Rogers, a co-author on the study and long-time leopard seal researcher. “They’re like the songbirds of the Southern Ocean. During the breeding season, if you drop a hydrophone into the water anywhere in the region, you’ll hear them singing.”

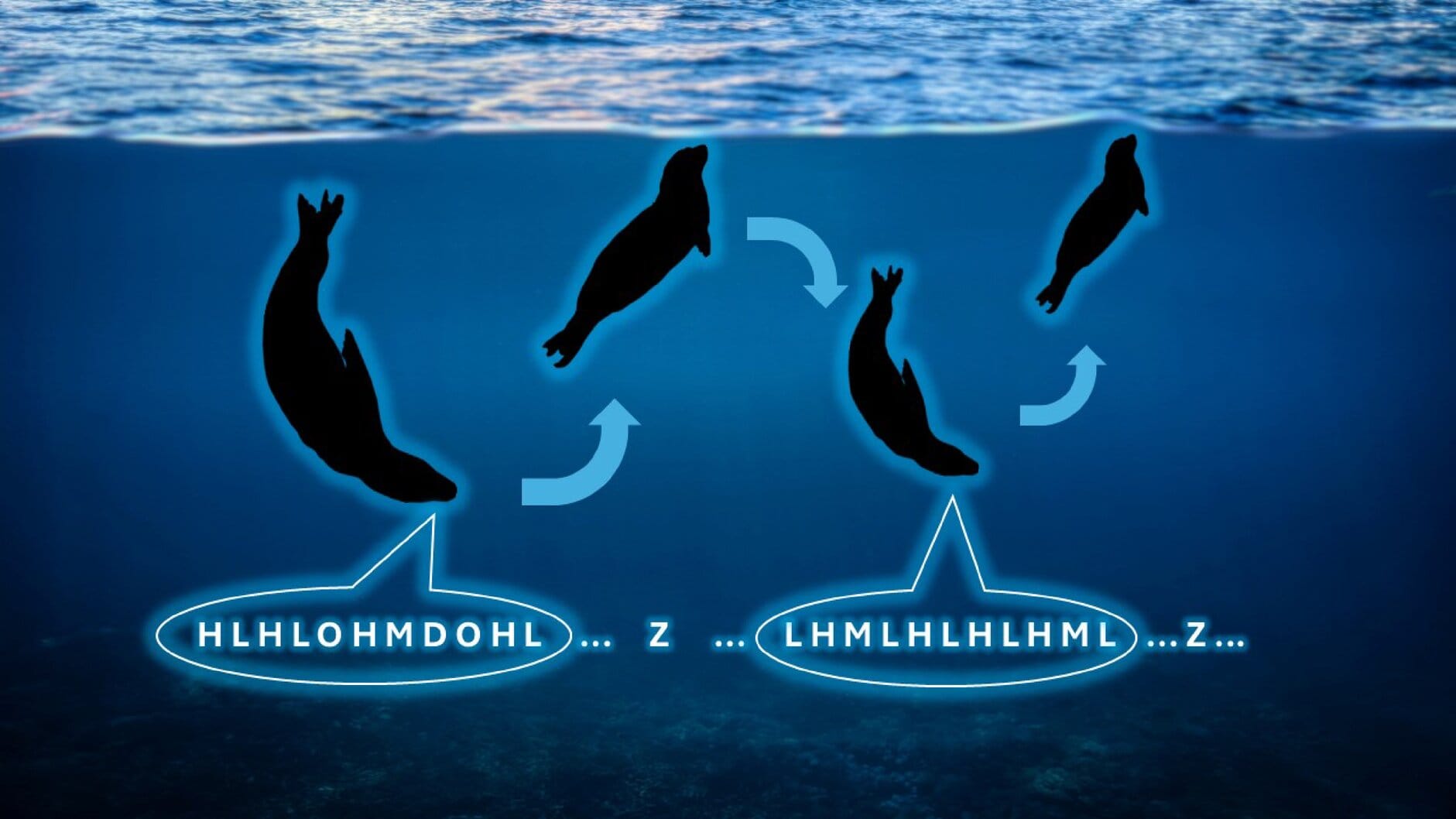

But these aren’t the random calls of a bored animal. The study reveals that leopard seal songs are constructed from five distinct vocal elements—think of them as notes in a musical scale. Each male arranges these five notes into a unique sequence, repeating it again and again, in much the same way a child might recite “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

Unlike humans, however, leopard seals do not sing to soothe offspring. These underwater soliloquies have an entirely different purpose—and one that carries evolutionary weight.

Songs of Strength and Seduction

Though the ice-covered Antarctic may seem devoid of life, it is actually teeming with activity—especially beneath the surface. For leopard seals, the singing season coincides with mating season. And while females may sing briefly during their short four-to-five-day fertility window, the males are the true vocal performers.

“The greater structure in their songs helps ensure that distant listeners can accurately receive the message and identify who is singing,” Chambers explains. “We think it’s a dual message. It might be ‘this is my patch’ to other males, and also ‘look how strong and lovely I am’ to the females.”

In other words, these seals are not just crooning for fun. They are declaring territory, asserting dominance, and wooing mates—all with a few carefully arranged vocal motifs. The study likens this behavior to the way many songbirds use repetitive melodies to communicate strength and fitness across distances.

But perhaps most fascinating is the way each seal creates a song that is uniquely his own. With only five basic call types to choose from, it’s the sequence—the order and rhythm—that defines an individual’s song.

“It’s a bit like each seal having its own name,” Chambers says. “They’re all using the same alphabet of five sounds—but the way they combine them creates a pattern that’s individually distinctive.”

Entropy, Nursery Rhymes, and the Predictable Power of Pattern

To understand the deeper science behind these vocal displays, the researchers turned to a concept from information theory: entropy. In this context, entropy measures how predictable a sequence of sounds is. Low entropy means a sound pattern is highly structured and repetitive; high entropy means it’s more random and chaotic.

When the team analyzed 26 male leopard seal songs, they found the entropy of the sequences closely matched that of human nursery rhymes. Not Beatles ballads. Not Beethoven’s symphonies. But the simplest, most repetitive melodies we use to teach babies: Baa Baa Black Sheep, Mary Had a Little Lamb, and Row, Row, Row Your Boat.

“Nursery rhymes are simple, repetitive, and easy to remember—that’s what we see in the leopard seal songs,” Chambers explains. “They’re not as complex as human music, but they aren’t random either. They sit in this sweet spot that allows them to be both unique and highly structured.”

This finding opens up new ways of thinking about animal communication. The balance between repetition and novelty—a low enough entropy to be understood, but enough variation to stand out—may be a sweet spot not just in human language but across the animal kingdom.

Echoes From the Ice Age

The recordings analyzed in the study weren’t made last year or even last decade. They date back to the 1990s, when Prof. Rogers was conducting her own Ph.D. research in Antarctica. To capture the sounds of these elusive singers, she would ride a bike across the ice to locate seals, mark them with dye during the day, and return at night with audio equipment to record their songs in the dark.

“They sing at night, so I would mark them during the day and go back out at night to visit each of the seals to get recordings from different males,” Rogers recalls.

At that time, her aim was to build a vocal profile of the species. But now, those old analog tapes have become a treasure trove of sonic data. With modern computational tools, Chambers and the team have been able to mine this auditory archive for new insights—suggesting that leopard seal songs may be more than just mating calls. They might represent a complex, evolving form of vocal communication passed down over generations.

Today, the researchers are eager to return to the ice with newer, more sophisticated tools. Their goal? To find out whether the “alphabet” of leopard seal calls has changed over the past 30 years, and whether these marine mammals pass on new call sequences the way humans pass on folk songs or dialects.

“We want to know if new call types have emerged in the population,” Chambers says. “And if patterns evolve from generation to generation. We’d love to investigate whether their ‘alphabet’ of five sounds has changed over time.”

Singing into the Future

This study doesn’t just offer a window into the acoustic lives of leopard seals—it opens a door into broader questions of communication, intelligence, and even culture in non-human species. The idea that a solitary predator could produce a structured, repeatable, and perhaps even personalized song suggests cognitive processes we’ve only begun to explore.

As the world’s oceans warm and Antarctic ice continues to melt, understanding how species like the leopard seal use sound to survive and interact is more important than ever. Their habitat is fragile. Their songs are echoes of resilience in a world that is changing fast.

And yet, through it all, the leopard seal continues to sing—its melody a haunting and hopeful reminder that intelligence takes many forms, and sometimes, the most profound messages are whispered beneath the waves.

More information: Leopard seal song patterns have similar predictability to nursery rhymes, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-11008-8