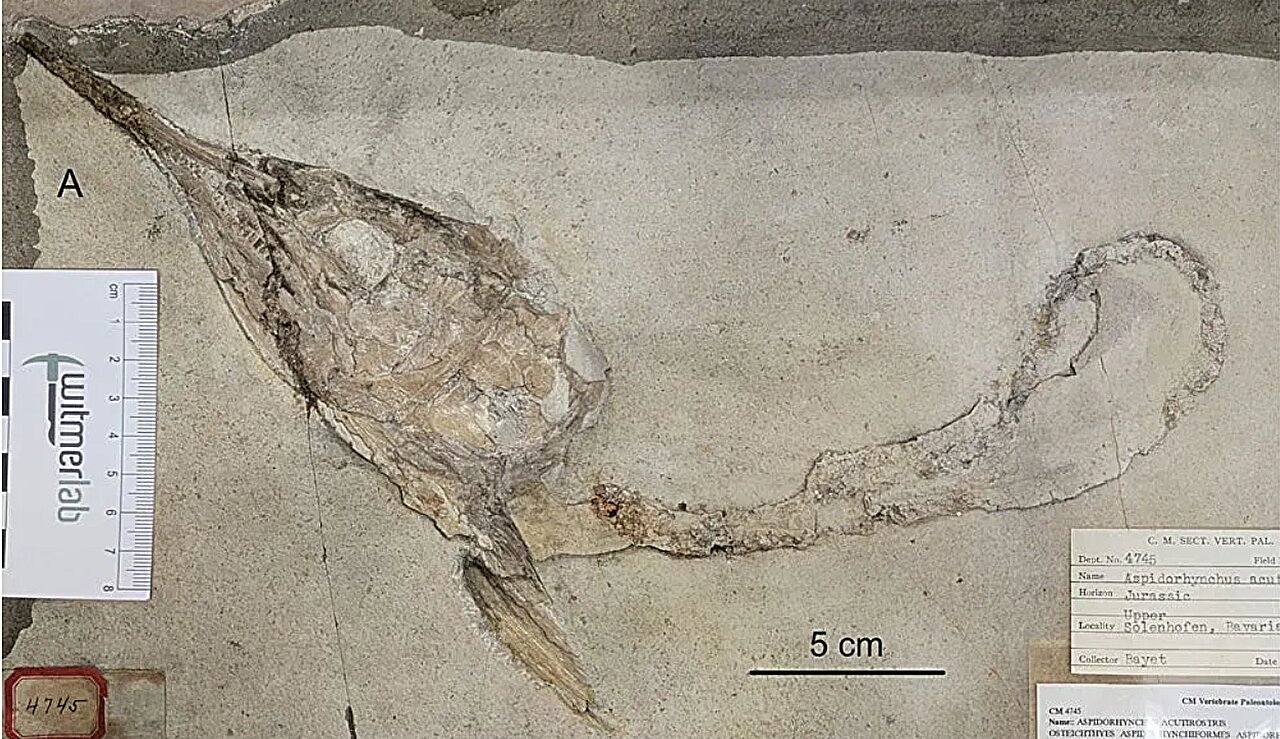

The story starts with a fossil that looks more like the aftermath of a prehistoric crime scene than a quiet remnant of deep time. In the limestone beds of the Solnhofen Archipelago in Bavaria, researchers Martin Ebert and Martina Kölbl-Ebert uncovered a rare and startling type of fossil: the decapitated head of the ancient predator Aspidorhynchus, still attached to its trailing gastrointestinal tract.

Such fossils are almost unheard of. Heads alone are unusual; heads with guts still clinging like ghostly ribbons are nearly miraculous. They do something most fossils cannot—they reveal not only what these hunters ate, but also how they themselves met their end. It is a window into life and death in the Late Jurassic seas, preserved with a vividness that seems almost deliberate.

From these remains, a story emerges: what Aspidorhynchus hunted, how it swallowed, and what may have ultimately torn it apart.

The Predator with a Spear for a Jaw

To understand the mystery, the researchers first had to understand the creature itself. Aspidorhynchus once patrolled the waters around the Solnhofen Archipelago, a region famous for its exquisite fossils. About one meter long and making up roughly 4% of all known fish fossils from the area, the fish was built for speed. Its most striking feature was its long, spear-like upper jaw, reminiscent of modern marlins and swordfish.

“Judging from their body shape and fin morphology, it is highly likely that Aspidorhynchus was a pursuit predator. From its stomach contents, we know that it fed mainly on small teleosts (Orthogonicleithridae). There is evidence that the Orthogonicleithridae were schooling fish, and it is assumed that Aspidorhynchus, with its long upper jaw, may have used a hunting technique similar to modern swordfish,” explained Dr. Ebert.

This portrait paints a vivid image: a sleek Jurassic hunter slicing through water, striking at schools of small fish with the precision of a blade. And with 343 specimens examined for the study, researchers were able to look deeper into its behavior than ever before.

What they did not expect was that 16% of those specimens were cleanly and completely decapitated.

Inside the Stomach of a Long-Dead Hunter

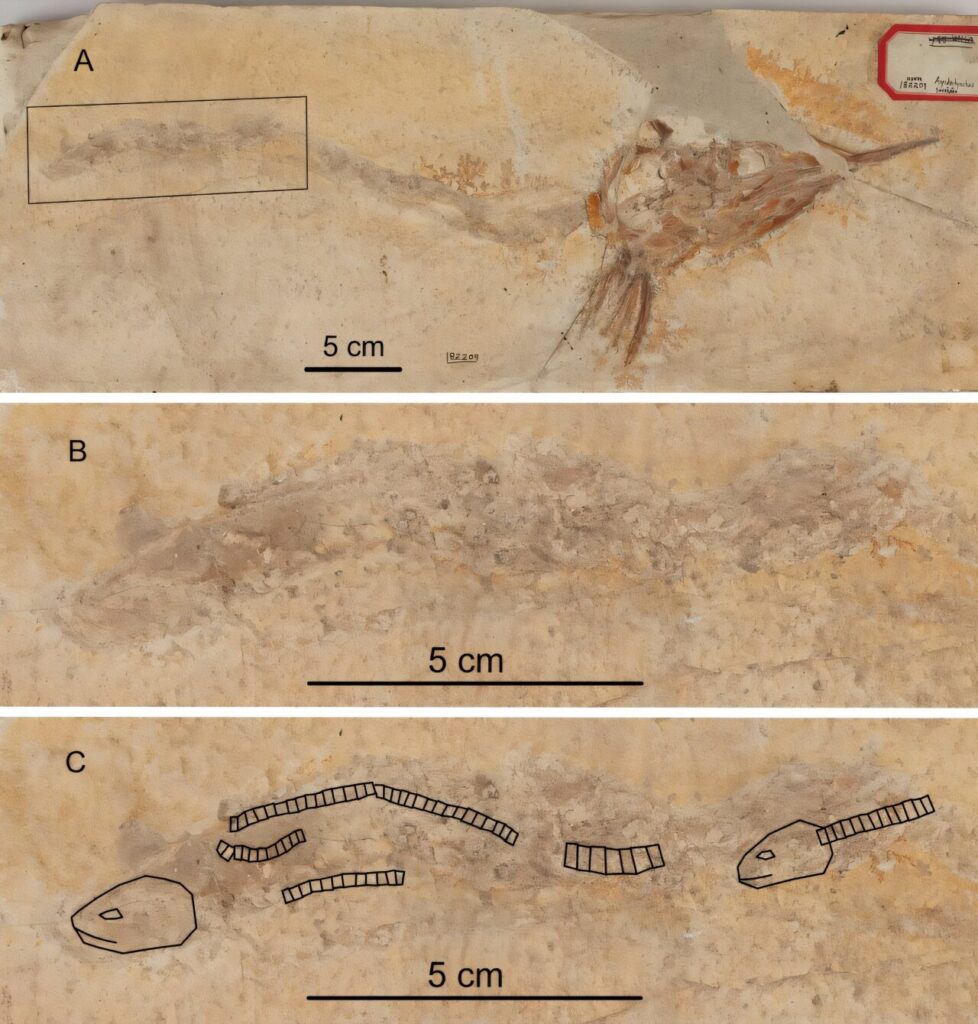

The unusual condition of these fossils offered something precious: unhindered access to Aspidorhynchus gut contents. Normally, the thick ganoid scales of the fish obscure what lies inside. But with the heads torn off and most of the body gone, the internal remains were preserved in clear view.

Some specimens revealed predictable meals. Many contained the bones of small juvenile teleosts—fish small enough to be swallowed whole without trouble. Others, however, told a more dramatic tale. Specimen GZG.RF.999, a 56-centimeter Aspidorhynchus, had somehow engulfed an Allothrissops measuring 16 centimeters. An ambitious meal by any standard.

Still stranger was specimen GZG.RF.998, found with a small ganoin-scaled fish lodged in its mouth. The position of the stuck prey suggests a tragic end: the fish could not close its mouth or breathe properly and may have effectively drowned. The researchers note that modern fish sometimes die the same way when attempting to swallow prey too large for them.

Then there was the unexpected crustacean. In one specimen, scientists found a Knebelia schuberti in the stomach, a type of prey Aspidorhynchus was not known to eat. How it ended up there is a mystery left open—perhaps accidental, perhaps opportunistic, perhaps something else entirely.

Each discovery adds a brushstroke to the portrait of a hunter that was sometimes skilled, sometimes unlucky, and occasionally surprising.

When the Hunter Becomes the Hunted

If the gut contents reveal what Aspidorhynchus ate, the decapitations reveal what ate them. The researchers propose that these fish fell victim to grabber predators—large marine hunters that attacked differently than Aspidorhynchus itself. Instead of swallowing prey whole, these predators seized victims by the tail and thrashed violently, biting and shaking until the head tore free.

This method neatly explains the strange fossils the researchers encountered: isolated skulls with guts still attached, bodies missing entirely.

An anatomical weakness in Aspidorhynchus made them particularly vulnerable. Their vertebral centra were incompletely ossified, leaving a natural weak point between the skull and the body. Under the right force—a sudden twist or violent pull—the head could detach cleanly.

The researchers quote David Bellwood to illustrate how this kind of separation naturally brings the guts along with the head. In scientific gut content analysis, he advises to “cut the head at the dorsal connection with the spine, then pull the head off, and the guts come with it.”

Something in the Jurassic seas was doing exactly that.

As for the likely culprits, Dr. Ebert explains, “In the Solnhofen archipelago, we know of 2–4 m long Ichthyosaurus, marine crocodiles, and even larger Pliosaurs, for whom this was certainly no problem.”

These were predators capable of delivering the kind of brutal, sudden force needed to tear a head from a body. It paints a vivid, if violent, picture of life in those ancient waters: swift hunters pursued by even swifter, stronger killers.

Why This Discovery Matters

This study offers an intimate look at an ancient ecosystem. By examining the decapitated heads of Aspidorhynchus, scientists reconstructed both the feeding behavior of the species and the predation pressures it faced. Rare fossils with preserved guts allowed a clearer view into the dietary habits of a predator that once dominated its environment. Even more remarkable, the unusual state of preservation revealed the dramatic final moments of these fish, showing how they were violently killed by larger predators.

Perhaps most importantly, the research showcases the extraordinary fossil preservation of the Solnhofen Archipelago. These limestones do not merely preserve bones—they preserve behaviors, relationships, and sometimes the final seconds of life. They allow scientists to read stories written 150 million years ago in exquisite detail.

Through these severed heads and ancient meals, the study brings us closer to the living world of the Late Jurassic, reminding us that even in deep time, every predator has a predator, and every fossil has a story waiting to be told.

More information: Martin Ebert et al, Hunted hunters – prey of Aspidorhynchus (Actinopterygii) within isolated gastrointestinal tracts from the late Jurassic of the Solnhofen Archipelago, Fossil Record (2025). DOI: 10.3897/fr.28.169110