Deep beneath the limestone hills of southern Italy, in the stillness of Lamalunga Cave, a face has waited more than 130,000 years to answer a question scientists have argued over for decades. It is a question about survival, cold winds, bone, breath, and the mysterious architecture of a Neanderthal’s forward-projecting face. For years, paleontologists wondered whether this distinctive midfacial shape—a pronounced push of the middle face toward the front—was a direct evolutionary tool designed to warm icy air during the harsh glacial ages of Europe.

The idea made intuitive sense. If Neanderthals lived in cold, dry climates, their noses might have been engineered by nature for endurance, for warming and moisturizing each breath before it reached their lungs. But intuition is not evidence. To settle the debate, scientists needed to inspect the delicate interior of a Neanderthal nasal cavity. The problem was simple and maddening: such fragile structures rarely survive fossilization. Which meant the mystery endured.

Then came Altamura Man.

A Fossil Wrapped in Stone and Silence

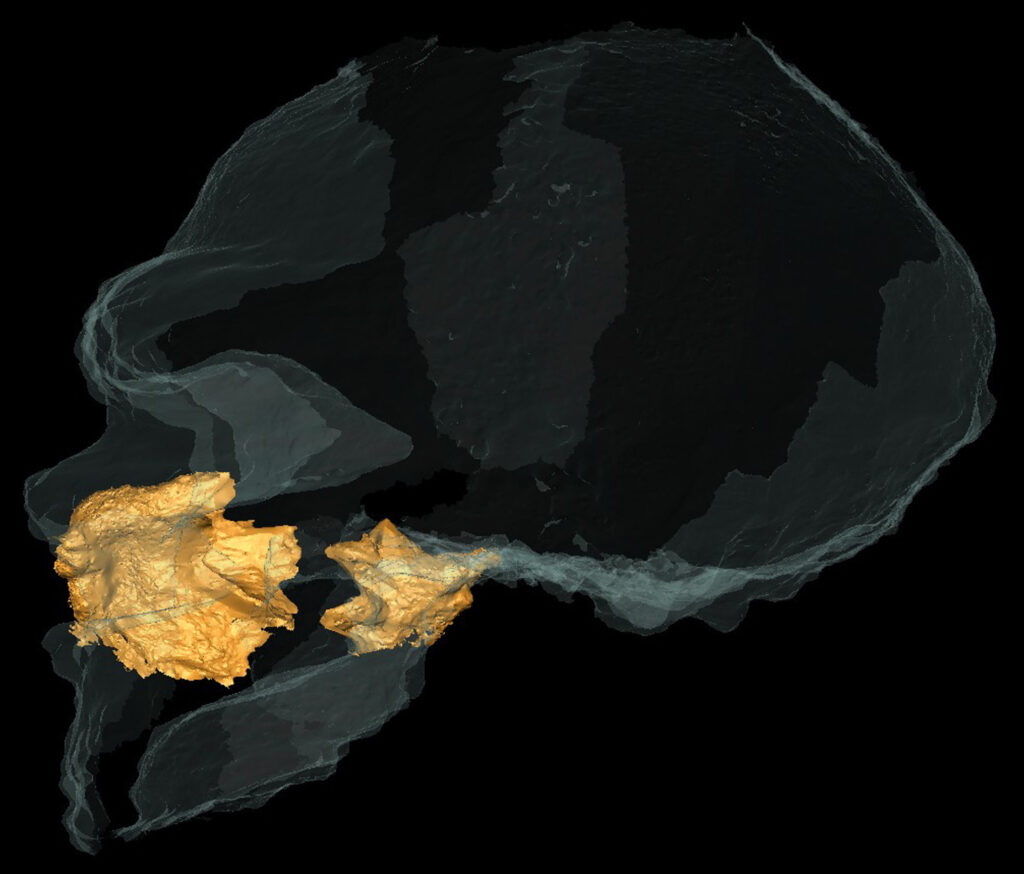

Altamura Man is not a fossil that can be carried into a lab or placed gently on a table. He lies embedded in a rock chamber so tight and fragile that even a breath in the wrong direction could damage him. But what makes him immovable is also what makes him extraordinary: his skeleton, encased in a glittering coat of calcite, is preserved with a level of detail almost unheard-of in Neanderthal remains. He is a sculpture shaped by time, untouched, unshifted, protected.

Estimated to be between 130,000 and 172,000 years old, this ancient Neanderthal became the silent custodian of secrets no other fossil could reveal. And so, instead of lifting him from his stone cradle, scientists brought their tools to him.

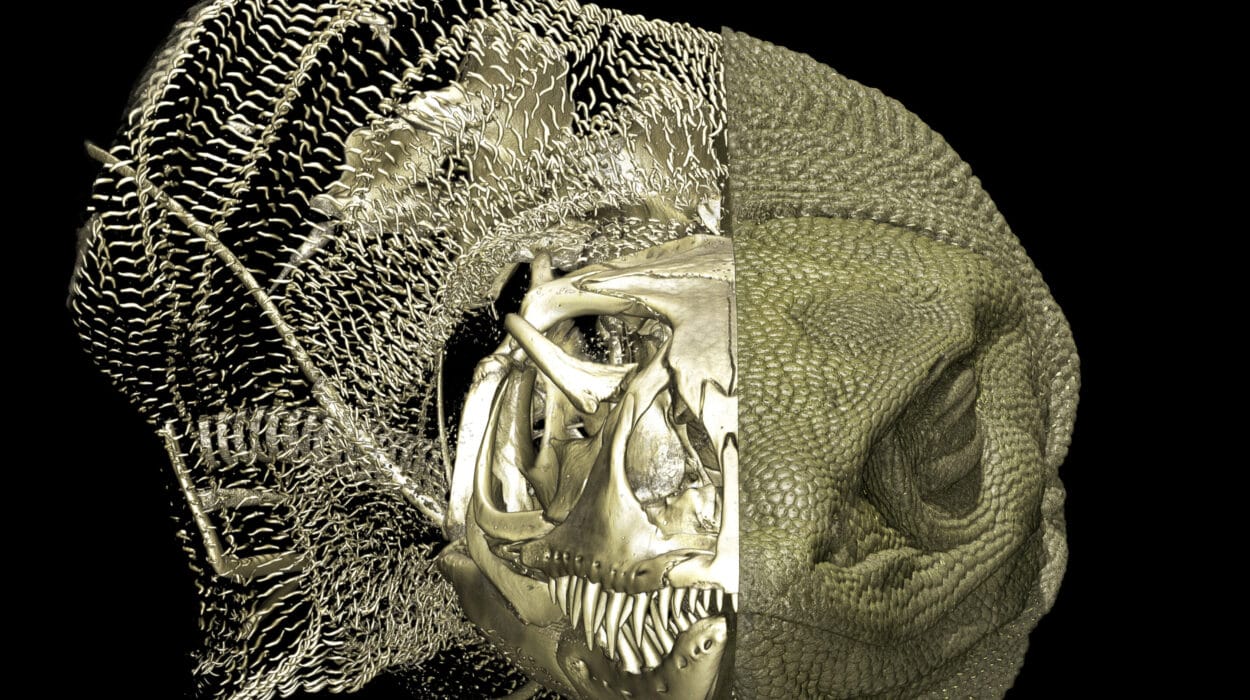

Constantino Buzi from the University of Perugia and his colleagues devised a plan that bordered on surgical. They threaded tiny endoscopic cameras—slender, delicate, able to snake through narrow gaps—into the nasal cavity of the embedded skull. These cameras traveled where no human eye could go, capturing images of the internal bone structures with astonishing clarity. Those images were then transformed into 3D models, allowing researchers to explore a nasal cavity sealed off from the world for over a hundred millennia.

If there were any unique internal features adapted to cold air, this was where they would be found.

When the Expected Is Absent

As the models formed, one unexpected truth emerged: those long-theorized internal nasal adaptations were simply not there.

For decades, scientists had imagined that Neanderthals might possess specialized bone structures within the nasal cavity—features that could warm or moisten air more effectively than ours. These internal formations, had they existed, would have supported the idea that Neanderthals’ distinctive facial projection evolved in direct response to an icy climate.

But the cave-preserved evidence said otherwise.

Instead, the structure of the Altamura Man’s nose looked strikingly familiar, echoing the nasal anatomy of modern humans. The researchers summarized their conclusion with unmistakable clarity: “Our main finding is that the inner nasal autapomorphies hypothesized for the species Homo neanderthalensis are not present in this individual and, therefore, should not be considered Neanderthal specific features.”

The absence of these features reshaped the entire debate. If the nose wasn’t internally adapted for extreme cold in this way, then its external shape—the famous forward-projecting Neanderthal face—could not be explained as a cold-weather tool alone. Something else had shaped these ancient people.

The Face That Carried Many Stories

With the cold-adapted-nose theory collapsing, the researchers turned to what their findings did suggest. The distinct facial anatomy of Neanderthals, they argued, likely resulted from a complex combination of influences instead of a single dramatic adaptation.

Part of it was inheritance—traits passed down from earlier human ancestors, embedded deep in evolutionary history. Another part came from the dynamics of bone growth itself, the subtle coordination of tissues and structures as they expanded and strengthened across a lifetime. And finally, Neanderthals were large-bodied humans, robust and powerful, and their faces needed to support the demands that came with such a physique.

Yet none of this diminishes the impressive efficiency of the Neanderthal nose. Even though its inner structure was not uniquely specialized, it still operated remarkably well in recovering heat and moisture from exhaled breath. In the cold, this mattered tremendously. Every degree of warmth recaptured, every drop of moisture retained, helped conserve energy and stave off dehydration. The nose may not have driven the shape of the face, but it certainly played its role in helping Neanderthals endure the frigid Ice Age world around them.

A Discovery That Reshapes an Ancient Puzzle

This study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, does more than settle a long-standing debate—it changes the way we envision the Neanderthal face itself. Scientists have long sought to map the connection between form and function, between the bones we see and the environments those bones endured. But Altamura Man reminds us that evolution is rarely guided by a single factor. Instead, it is a patient weaving of multiple threads over thousands of generations.

His preserved nasal cavity shows that survival is not always about dramatic adaptations. Sometimes, it is about the blending of old traits, natural growth, and bodily needs that shape a species in ways not immediately obvious.

And in this case, the forward-pushing Neanderthal face was sculpted by more than cold winds. It was shaped by ancestry, biology, and the physical demands of being a strong, cold-climate human—not by a single nasal innovation.

Why This Research Matters

Understanding how Neanderthals evolved is not simply a matter of curiosity. It is a way of reading our own deep history, of understanding the paths humanity might have taken and the paths we share. The discovery from Altamura Man shows that even traits long assumed to be cold-weather adaptations may have roots far more complex and nuanced.

It reminds us that evolution does not act with straightforward intention. It works through the quiet interplay of inherited structures, environmental pressures, and the constraints of growing bodies. And when scientists uncover a fossil as perfectly preserved as Altamura Man, they also uncover a moment of clarity—one that shifts the story of our ancient relatives.

What emerges from this research is a more textured portrait of Neanderthals: resilient, efficient, shaped by many forces, and far more similar to us in nasal structure than once imagined. The answers came not from speculation but from the silent depths of a cave, where a long-buried face finally revealed what it had known all along.

More information: Costantino Buzi et al, The first preserved nasal cavity in the human fossil record: The Neanderthal from Altamura, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2426309122. www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2426309122