Life has never existed in isolation. From the very beginning, it has been cradled by the Earth, shaped and reshaped by its rhythms. Wind, rain, sunlight, ice, volcanic fire, and ocean tides—all have been the hands that molded life’s form. But one of the most powerful forces behind the ever-shifting patterns of evolution has been the Earth’s climate. Whether warming or cooling, steady or abrupt, the changing climate has always acted as a quiet sculptor, carving out new forms, ending lineages, and inspiring adaptations so astonishing that they seem like works of genius. And in many ways, they are—but the genius lies not in planning, but in persistence.

As the Earth breathed in and out across eons—glaciers forming and melting, seas rising and falling, forests growing and dying—life responded. Sometimes it adapted. Sometimes it moved. Sometimes it vanished. But always, life changed. Climate change is not a modern invention. It is an ancient dance partner of evolution, one whose steps have shaped the story of life in ways we are only beginning to understand.

The Earth’s Unpredictable Past: A Stage of Constant Transformation

Our planet’s climate has never been still. Even before the first bacteria wriggled into existence some 3.5 billion years ago, the Earth was already experiencing wild fluctuations in temperature and atmosphere. The early Earth was a volatile place—bombarded by asteroids, wracked by volcanic eruptions, and slowly cooling from its primordial heat. Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane helped trap heat in the atmosphere, preventing the planet from freezing over completely during a time when the Sun was still young and dimmer than it is today.

One of the first major climate events that nearly extinguished life was the so-called “Snowball Earth” episodes around 700 million years ago, when glaciers may have covered the planet from pole to equator. These icehouse conditions were followed by sudden warming periods, caused by volcanic CO₂ buildup. Such events were not merely destructive; they were evolutionary crucibles. The aftermath of Snowball Earth saw a bloom of multicellular life, as organisms that survived were forced to adapt to extreme shifts in environment.

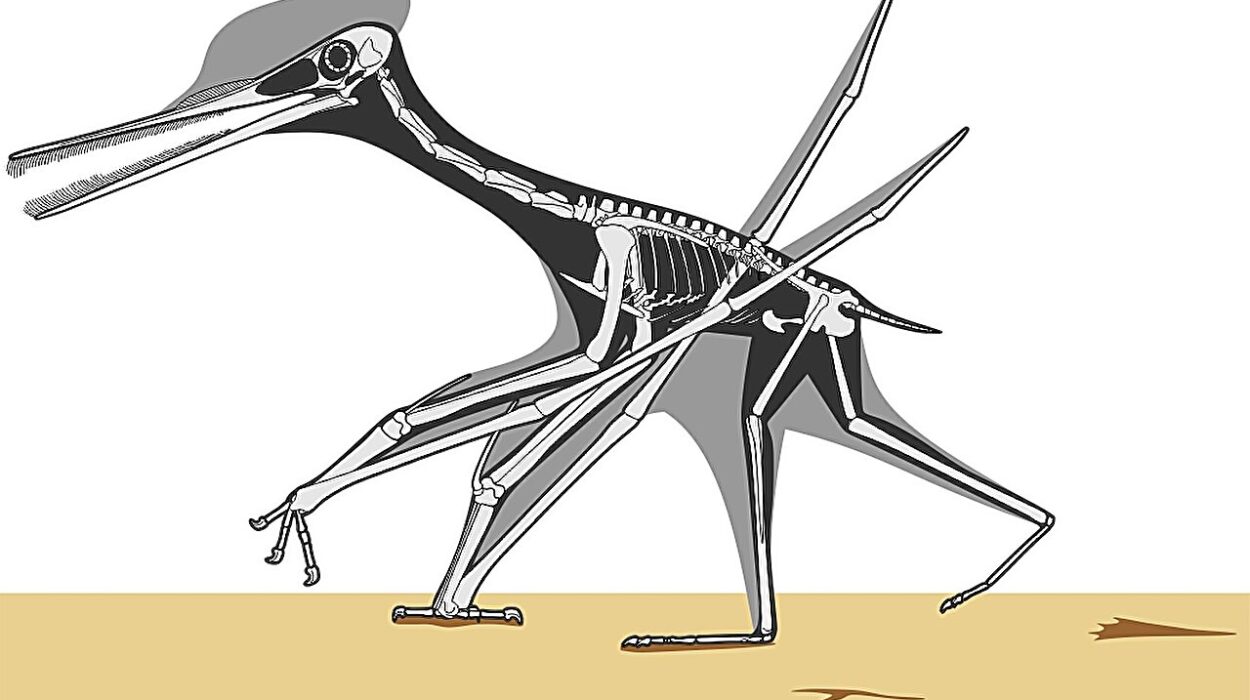

From these deep glacial eras to the hothouse conditions of the Mesozoic—when dinosaurs roamed steaming jungles and shallow seas—climate swings have pushed evolution down paths it would not have otherwise taken. Climate determines habitat, and habitat determines opportunity. When the climate shifts, the game of survival changes its rules.

The Cambrian Explosion: A Spark in the Climate Storm

Roughly 540 million years ago, something extraordinary happened. Life, which had been relatively simple for billions of years, suddenly blossomed in complexity. This event, known as the Cambrian Explosion, saw the rapid emergence of most major animal groups, including ancestors of arthropods, mollusks, and vertebrates.

Scientists have long debated the causes of this biological burst. One theory places climate at the heart of it. Before the Cambrian, oxygen levels in the oceans were low. But as Earth’s tectonic plates shifted, new volcanic activity and erosion patterns may have led to higher nutrient flow into the seas. This, in turn, increased photosynthesis by marine microbes, which raised oxygen levels. A warming climate might have helped sustain this productivity. The result was an ocean teeming with energy, allowing larger and more complex organisms to evolve.

Thus, a change in climate—a subtle warming of the oceans combined with higher oxygen levels—may have unlocked the genetic potential that had been building in early life. It’s a reminder that evolution doesn’t just require mutation. It also requires opportunity. And climate, more than anything else, provides or withholds that opportunity.

Desert Bones and Mammal Dreams: The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum

Fast forward to about 56 million years ago. Earth was already warm, with no ice caps, and most land was covered in lush forests. But then, in an event known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), global temperatures soared by as much as 8°C in just a few thousand years. The cause? A massive release of carbon into the atmosphere, likely from volcanoes, methane hydrates, or a combination of both.

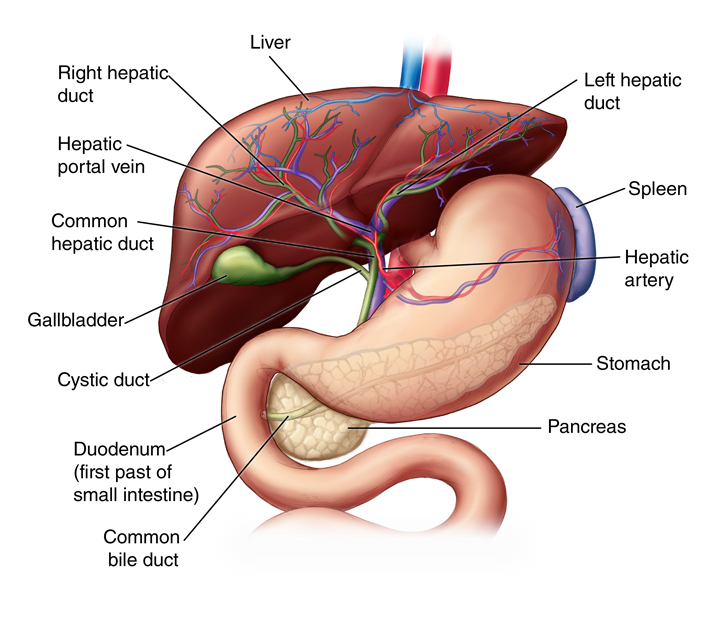

The PETM was a period of chaos—and adaptation. The oceans turned more acidic, disrupting marine life. Forests spread into higher latitudes, and rainfall patterns shifted. For many species, it was a death sentence. But for mammals, it was a new beginning.

In this steamy world, small forest-dwelling mammals began to diversify rapidly. Some took to the trees; others grew larger; some began to develop more complex behaviors and diets. Among them were the ancestors of primates—our own distant relatives. The PETM marked one of the most significant evolutionary expansions in mammalian history, setting the stage for what would eventually become the Age of Mammals.

Again, climate was the catalyst. It opened ecological niches and forced migrations. It caused extinctions but also cleared space for new innovations. Climate doesn’t just destroy. It clears the table and invites a new game.

Ice and Intellect: The Pleistocene and the Rise of Humanity

Of all the climate-driven transformations, none is more personal than the one that led to us.

The last 2.6 million years of Earth’s history—the Pleistocene epoch—were dominated by cycles of glaciation. Massive ice sheets grew and receded in rhythm with changes in Earth’s orbit, axial tilt, and solar radiation. These “ice ages” reshaped landscapes, created vast deserts, carved out valleys, and drove migrations across continents.

And in this harsh, unstable world, hominins evolved.

Our ancestors didn’t emerge in a stable paradise. They evolved in a world that was constantly shifting—forests becoming savannas, lakes appearing and disappearing, food sources changing unpredictably. Climate change may have been the greatest challenge our lineage ever faced. And in facing it, we changed.

Bipedalism—walking on two legs—freed our hands to use tools. Larger brains evolved to help us adapt to varied environments. Social structures became more complex, allowing group survival in uncertain times. Fire was harnessed not just for warmth, but for cooking and protection. Language emerged as a tool for cooperation, memory, and planning.

All of this happened not in spite of climate instability—but because of it. The volatility of the Pleistocene selected for flexibility, intelligence, and creativity. Humans are not a product of one climate zone. We are a species forged by chaos, by wind and ice and uncertainty. We are evolution’s answer to unpredictability.

Mass Extinctions and New Beginnings

Climate change has not always been slow or survivable. There have been times when it came like a hammer.

The most catastrophic climate-driven event in Earth’s history was the Permian-Triassic extinction, around 252 million years ago. Sometimes called “The Great Dying,” it wiped out over 90% of marine species and 70% of land species. The cause? A massive release of greenhouse gases from Siberian volcanism, which triggered runaway warming, ocean acidification, and oxygen loss.

Life on Earth was nearly extinguished. But in the aftermath, evolution took a new turn. The survivors—mostly small, resilient species—gradually diversified. From the ashes of extinction, new ecosystems arose. Dinosaurs, and later mammals, would not have existed if not for this apocalyptic reset.

Another extinction, around 66 million years ago, wiped out the dinosaurs. While the primary cause was a giant asteroid impact, it was the climate consequences—global cooling, darkness, and collapse of food chains—that delivered the final blow. Again, mammals, once small and obscure, rose to prominence in the vacant world.

These events show that climate-driven extinctions, though tragic, are also engines of evolutionary change. They create space for innovation. They are cruel, but not meaningless.

Adaptive Radiations: Evolution’s Rapid Response Team

One of the most remarkable outcomes of climate-driven change is the phenomenon of adaptive radiation. This is when a single ancestral species rapidly diversifies into many new forms, usually in response to new environments or opportunities.

When climate alters a habitat—drying a lake, raising a mountain, isolating an island—it creates these opportunities. The classic example is Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos Islands. Different islands had different climates, and over time, the finches evolved beaks specialized for seeds, insects, or flowers. One ancestral species gave rise to a dozen, each fine-tuned to its niche.

This isn’t just true for birds. Cichlid fish in African lakes, marsupials in Australia, and mammals after the dinosaur extinction—all show how climate-induced changes in the environment drive rapid bursts of evolutionary innovation.

Evolution is often portrayed as slow and gradual. But when the climate shifts suddenly, life doesn’t always wait. It adapts, quickly and creatively, using the raw materials of genetic variation and natural selection.

Climate and the Evolution of Biodiversity Hotspots

Some of the richest regions of biodiversity on Earth—like the Amazon, the Congo Basin, or Southeast Asia—owe their diversity to long-term climatic stability punctuated by periods of change. These areas have acted as “refugia” during past climate upheavals, allowing species to survive while others perished.

But even within these refuges, climate has shaped evolution. Periodic shifts in rainfall, temperature, and sea level have fragmented forests, isolated populations, and reconnected them again. This process of isolation and reunion fuels speciation—the splitting of one species into two.

Rainforests, once thought to be evolutionary museums where ancient species persist unchanged, are now seen as engines of innovation. Climate change, even subtle and cyclical, has driven the diversification of countless insects, birds, plants, and mammals.

Biodiversity, then, is not just a product of favorable climate. It is a product of changing climate—of challenge, disruption, and the resilience of life to adapt to new realities.

Lessons from the Past for an Uncertain Future

The story of climate and evolution is not just a tale of the past. It is a warning for the present.

Today, human activity is driving climate change at an unprecedented rate. Carbon dioxide levels are higher than at any time in the past 3 million years. The rate of warming is faster than most past natural events. Oceans are acidifying. Ice is melting. Species are migrating, declining, or going extinct.

Some might argue: hasn’t life always adapted? Isn’t climate change a natural part of Earth’s history?

Yes—and no.

Life can adapt, but it needs time. The rapid pace of current climate change leaves little room for gradual evolution. Coral reefs are bleaching faster than they can recover. Insects and birds are mismatched with the plants they pollinate. Migration corridors are blocked by cities, roads, and farmland. Natural selection cannot act if there is no population left to select from.

We are conducting an experiment unlike any in the planet’s history—altering the climate not over millennia, but decades. The past shows that life is resilient, but it also shows that mass extinctions are very real. And unlike in previous ages, we now have the power not just to observe these changes, but to cause—or prevent—them.

Climate, Consciousness, and the Moral Arc of Evolution

In the end, the story of climate-driven evolution is not just about genes, fossils, and ecosystems. It is about consciousness—ours.

We are a species that owes its very existence to climate change. Our brains, our creativity, our societies were forged in the crucible of environmental instability. But now, for the first time, we have the capacity to understand that process—and to influence it.

This is not a power to be taken lightly. With it comes responsibility: to preserve the ecosystems that nurture life’s diversity, to slow the changes we are accelerating, and to give evolution the space it needs to continue its ancient dance.

The climate will always change. But how it changes—and what survives because of it—is now, in part, up to us.

Evolution is no longer just a process of the past. It is a story we are still writing.