High in the Pollino massif of southern Italy, a cave has been quietly holding its breath for thousands of years. Stone walls absorbed footsteps, whispers, rituals, and grief long before written history reached this rugged landscape. Today, that silence has finally been broken.

An international team of researchers led by scientists from the Max Planck Harvard Research Center for the Ancient Mediterranean in Leipzig and the University of Bologna has reconstructed, for the first time, the genetic and social profile of a Protoapennine community that lived in northwestern Calabria about 3,500 years ago. Their work, published in Communications Biology, transforms Grotta della Monaca from a shadowy archaeological site into a place populated by real people with families, movements, diets, and social rules.

This is not a story of kings or empires. It is the story of a small mountain community, preserved in bone and DNA, finally stepping back into the light.

Inside the Cave Where Lives Were Laid to Rest

Grotta della Monaca lies deep within the Pollino massif, near Sant’Agata di Esaro in the province of Cosenza. The cave has long been known as one of Calabria’s most important prehistoric sites. Archaeologists have already recognized it for its early evidence of copper and iron ore exploitation and for its use as a funerary space.

What the researchers did next changed everything. By analyzing ancient DNA extracted from human remains dated between 1780 and 1380 BCE, they were able to place this community within the broader genetic landscape of the Mediterranean Bronze Age. The cave was no longer just a hollow in the mountain. It became a lens through which an entire way of life could be seen.

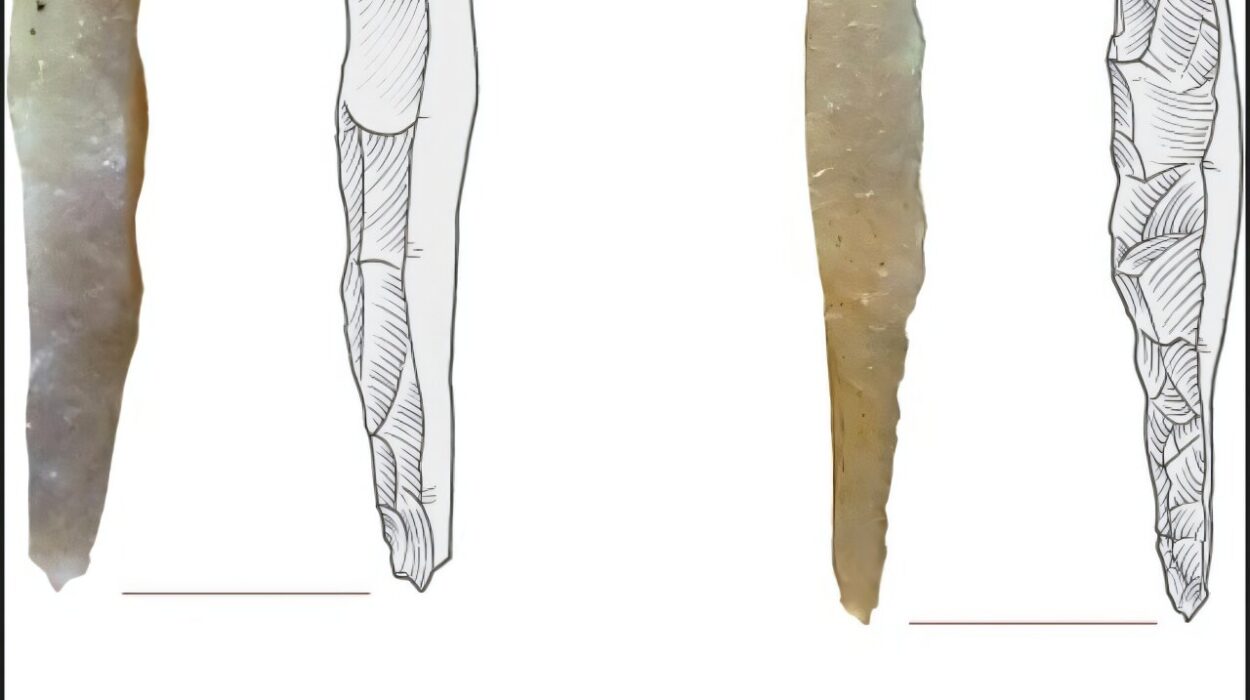

The Protoapennine culture, a cultural horizon attested in Southern Italy around the Middle Bronze Age, had left behind artifacts and burial traces. What had been missing was the people themselves—their relationships to one another, their origins, and how they fit into the shifting human tapestry of prehistoric Europe. Grotta della Monaca provided that missing link.

Tracing Ancestry Across Water and Stone

As the genetic data came into focus, a surprising picture emerged. The community buried in Grotta della Monaca shared strong genetic affinities with Early Bronze Age groups from Sicily. This connection speaks of contact across the Strait of Messina, a narrow stretch of water that has long linked Calabria and Sicily.

Yet something was missing.

“Our analysis shows that the Grotta della Monaca population shared strong genetic affinities with Early Bronze Age groups from Sicily, yet lacked the eastern Mediterranean influences found among their Sicilian contemporaries,” explains Francesco Fontani, first author of the study and affiliated researcher at the Max Planck Harvard Research Center for the Ancient Mediterranean. “This suggests that, while in contact across the Strait of Messina, Tyrrhenian Calabria followed its own demographic and cultural trajectories during prehistory.”

In other words, this was not a passive community absorbing influences from every direction. Despite contact and exchange, they followed their own path. Their genetic profile reflects a local story shaped by selective connections rather than broad assimilation.

A Community That Was Small, But Not Isolated

At first glance, a mountain cave burial site might suggest isolation. The genetics told a different story. Among the individuals studied, two carried ancestral links to populations from northeastern Italy. These traces hint at long-distance mobility and gene flow across the Italian peninsula, even during a period when travel was slow and landscapes were unforgiving.

The genomes also revealed contributions from European hunter-gatherers, Anatolian Neolithic farmers, and Steppe pastoralists. These ancestral components were common in Bronze Age Europe, but here they formed a distinctive local signature. The people of Grotta della Monaca were not genetic outsiders, nor were they carbon copies of their neighbors. They were part of a broader human movement while maintaining a recognizable identity of their own.

This balance between connection and independence is one of the most striking features of the research. It paints a picture of a community that engaged with the wider world without losing its internal coherence.

The Cave as a Map of Family and Identity

The cave did more than preserve bones. It preserved relationships.

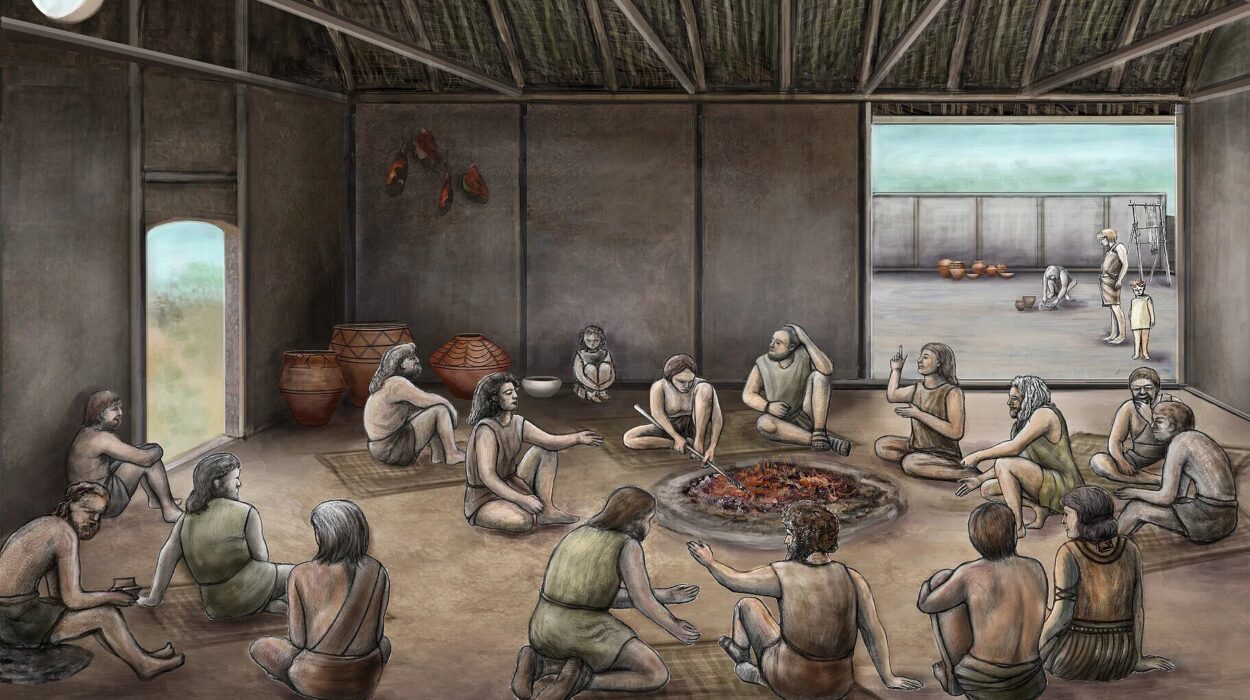

By combining genomic, archaeological, and anthropological data, the researchers uncovered patterns of sex- and kinship-based burial organization within the funerary area. The placement of individuals was not random. It reflected social structures, family ties, and shared identities that were meaningful to the living as they laid their dead to rest.

Then came a discovery that stopped the researchers short. Among the remains, they identified a parent-offspring union. This is the first genetic evidence of such a union ever documented in a prehistoric European context.

“This finding emphasizes the distinction between unambiguous biological evidence and its social meaning,” notes Alissa Mittnik, group leader at the Department of Archaeogenetics of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and co-senior author of the research. “This exceptional case may indicate culturally specific behaviors in this small community, but its significance ultimately remains uncertain.”

The data reveals what happened, not why it happened. The researchers are careful not to project modern interpretations onto ancient lives. What remains clear is that Grotta della Monaca holds evidence of social practices that were complex, possibly unusual, and deeply rooted in the community’s cultural framework.

Milk, Mountains, and a Genetic Paradox

Life in the Pollino massif was not easy. The terrain is steep, the climate demanding, and resources limited. Yet isotopic and genetic data reveal that this community practiced pastoralism and consumed milk and dairy products.

Here, the story takes an unexpected turn. Genetically, these individuals carried variants associated with adult lactose intolerance. By modern standards, they should not have been able to digest dairy without discomfort. And yet, they clearly relied on it.

According to Donata Luiselli, co-senior author of the study and head of the Ancient DNA Laboratory at the University of Bologna, this contradiction speaks volumes. She explains that it “illustrates how cultural adaptation can precede genetic evolution. These people had developed dietary strategies that allowed them to thrive in a challenging mountain environment, despite lacking genetic tolerance to lactose.”

Culture, in this case, moved faster than biology. Through processing, fermentation, or selective consumption, the community adapted its practices to its environment. Survival was not dictated by genes alone, but by knowledge passed down through generations.

Rethinking the Role of Caves in Protoapennine Life

The findings also reshape how archaeologists understand the function of caves in Protoapennine society. Rather than being marginal or symbolic spaces used only occasionally, Grotta della Monaca appears to have been a central place of communal importance.

The cave functioned as a collective burial site that reinforced shared community identity and familial bonds. It was a space where social memory was built layer by layer, generation after generation. The dead were not hidden away. They were gathered together in a place that mattered.

This interpretation challenges older assumptions and places caves at the heart of social life rather than at its edges.

A Small Community That Reshapes Big Histories

Felice Larocca, speleoarchaeologist and director of the research at Grotta della Monaca, underscores the broader importance of the site. “Situated over 600 meters above sea level in the Pollino massif, Grotta della Monaca continues to reveal key evidence about the first complex societies of Southern Italy—and, more broadly, about the biological and cultural roots of human diversity.”

What makes this research remarkable is not just what it reveals about one community, but how it reframes the story of prehistoric Europe. Large-scale migrations and sweeping cultural shifts often dominate narratives of the Bronze Age. Grotta della Monaca reminds us that small groups, living in difficult landscapes, made choices that mattered just as much.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it restores humanity to prehistory. It shows that even 3,500 years ago, communities navigated identity, mobility, family, and survival with creativity and resilience. Through genetic evidence, we see that cultural practices could override biological limitations, that social rules shaped burial traditions, and that local histories unfolded alongside broader population movements.

Grotta della Monaca teaches us that the past is not silent. It waits patiently for the right questions, the right tools, and the willingness to listen. By reconstructing the genetic and social profile of a Protoapennine community, researchers have given voice to people who lived, adapted, and cared for one another in a mountain cave long before history was written.

In doing so, they remind us that human diversity, in all its complexity, has always been part of the story.

More information: Francesco Fontani et al, Archaeogenetics reconstructs demography and extreme parental consanguinity in a Bronze Age community from Southern Italy, Communications Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-09194-2