For as long as humans have looked up at the night sky, the Milky Way has been both a familiar presence and a profound mystery. We live inside it, yet we have never truly known its childhood. How did this vast spiral of stars come to be? How did it grow from the early universe into the graceful galaxy we see today? These questions sit at the heart of astronomy, and in recent years they have become even more urgent. Observations from the James Webb Space Telescope have revealed galaxies in the early universe that appear unexpectedly massive and mature, challenging long-standing ideas about how galaxies assemble over cosmic time.

Against this backdrop of uncertainty, a new study has turned the telescope inward, toward our own cosmic home. By reconstructing the Milky Way’s life story in unprecedented detail, researchers have offered a rare glimpse into the galaxy’s earliest chapters, revealing a past far more turbulent than its serene present might suggest.

Meeting the Milky Way’s Long-Lost Twins

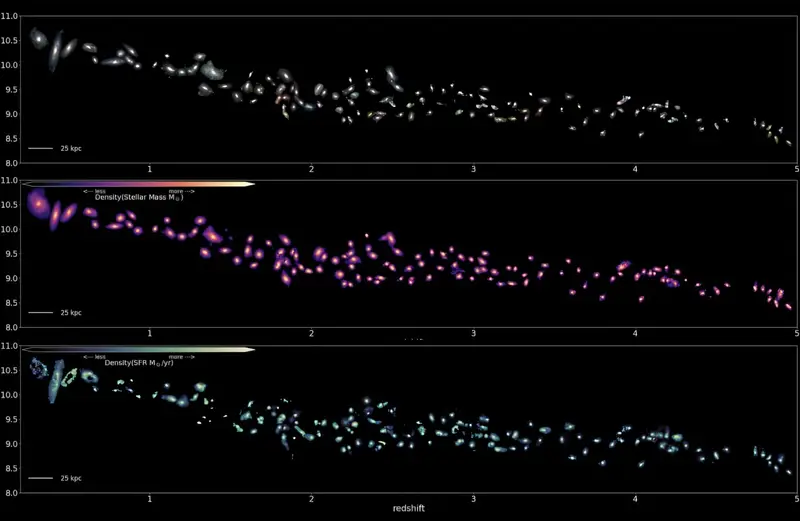

Instead of trying to directly observe the Milky Way’s past, which is impossible from within, the research team led by York University Ph.D. graduate Vivian Tan took a more imaginative approach. They searched the universe for 877 galaxies that closely resemble what astronomers believe the Milky Way looked like at different stages of its life. These galaxies, described as “Milky Way twins,” share similar masses and properties, but exist at varying distances from Earth. Because light takes time to travel, looking farther away also means looking further back in time.

By studying these distant twins, the team effectively rewound the Milky Way’s cosmic clock. Each galaxy became a snapshot of a different age, allowing the researchers to piece together a timeline stretching from the universe’s youth to its more mature epochs. The result is the most detailed reconstruction yet of how our galaxy may have grown over billions of years, from chaotic beginnings to structured adulthood.

The findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal, tell a story of dramatic transformation.

A Universe Still Finding Its Shape

The galaxies in the study span a remarkable range of cosmic history. They capture moments from when the universe was just 1.5 billion years old, roughly 12.3 billion years ago, up to when it reached an age of 10 billion years, about 3.5 billion years ago. This era corresponds to a time when the universe was only about 10% of its current age, a critical period when galaxies were evolving rapidly from small, irregular systems into the more stable disk galaxies seen today.

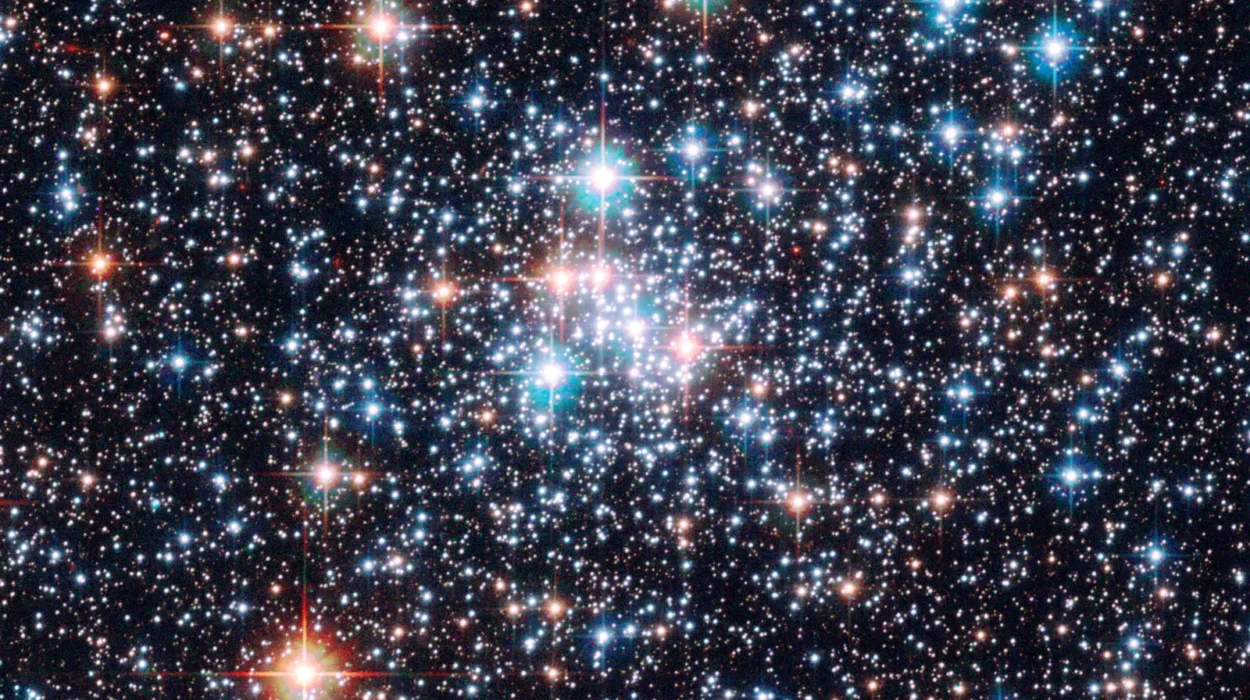

To peer into this distant past, the researchers combined data from the James Webb Space Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope. Webb’s observations came from the Canadian NIRISS Unbiased Cluster Survey, known as CANUCS. This program uses five massive galaxy clusters as natural gravitational lenses. Their immense gravity bends and magnifies the light from background galaxies, making otherwise faint and distant structures visible in striking detail.

This clever use of nature’s own lenses allowed the team to see features that would normally be far beyond reach, revealing the inner workings of galaxies at formative stages of their lives.

Growing from the Heart Outward

With Webb’s exceptional spatial resolution, the researchers created detailed maps of each galaxy’s stellar mass and star formation activity. These maps do more than show where stars exist; they reveal where stars were already in place and where new ones were actively forming at different moments in a galaxy’s evolution.

Across all 877 Milky Way twins, a clear and consistent pattern emerged. Galaxies like ours appear to grow from the inside out. In their earliest phases, these galaxies are dominated by dense, compact central regions packed with stars. As time passes, their outer regions rapidly accumulate mass and become the main sites of star formation. These expanding outskirts eventually form the extended disks and spiral structures characteristic of galaxies like the Milky Way today.

“Astronomers have been modeling the formation of the Milky Way and other spiral galaxies for decades,” says lead author Tan. “It’s amazing that with the JWST, we can test their models and map out how Milky Way progenitors grow with the universe itself.”

This inside-out growth paints a picture of galaxies steadily building themselves layer by layer, with their earliest cores acting as anchors for future expansion.

A Wild and Unsettled Youth

Perhaps the most striking revelation of the study lies in how different the Milky Way’s early life appears compared to its calm present. The youngest and most distant Milky Way twins show signs of extraordinary chaos. Their shapes are highly disturbed, with asymmetries and irregular features that hint at constant upheaval. These galaxies bear the marks of frequent interactions and mergers, environments where collisions were common and material was continually being pulled in from all directions.

Such conditions triggered intense bursts of star formation, lighting up galaxies in short but dramatic episodes. Far from being quiet or orderly, the early Milky Way seems to have lived through what could only be described as turbulent teenage years.

As the timeline progresses, the galaxies begin to settle. The older Milky Way twins display smoother, more stable structures. Their star formation becomes more evenly distributed, and the signs of major interactions grow rare. Together, these observations suggest that our galaxy experienced a far more chaotic past than astronomers had previously expected, before gradually calming into the structured spiral we inhabit today.

When Observations Challenge Theory

To understand how these observations fit into existing ideas, Tan and her colleagues compared their results with state-of-the-art computer simulations designed to model the evolution of Milky Way-like galaxies. In broad terms, the simulations agree with what Webb and Hubble reveal. They reproduce the overall inside-out growth pattern and the early clumpy, merger-driven activity.

Yet the comparison also exposes important gaps. The simulations sometimes struggle to recreate the extreme compactness of the earliest galaxies’ central regions. They also tend to underestimate how quickly mass builds up in the outer parts of galaxies between 8 and 11 billion years ago. These discrepancies matter because they point to missing or incomplete physics in current models, particularly related to how feedback processes, mergers, and disk formation are handled.

In the era of JWST, such differences are no longer minor details. They are crucial clues guiding astronomers toward more accurate theories of how galaxies truly evolve.

Pushing Further Back in Time

This work also highlights Canada’s growing role in JWST galaxy research. The NIRISS instrument, developed through partnerships involving the Canadian Space Agency and several research institutions, provided key data for the study. In return for these contributions, Canadian astronomers gained guaranteed observing time, enabling projects like this one.

According to co-author Adam Muzzin, the journey is far from over. “This study is a significant step forward in understanding the earliest stages of the formation of our galaxy,” he says. “However, this is not the deepest we have pushed the telescope yet. In the coming years, with the combination of JWST and gravitational lensing, we can move from observing Milky Way twins at 10% their current age to when they are a mere 3% of their current age, truly the embryonic stages of their formation.”

Future observations will expand these efforts, examining even larger samples of Milky Way-like galaxies and exploring additional features such as gas, dust, and internal motion. Several international teams already have observations scheduled, promising a rapidly deepening view of galactic origins.

Why This Story Matters

Understanding how the Milky Way formed is more than an exercise in cosmic nostalgia. Our galaxy is the environment that made the Sun, the Earth, and ultimately life itself possible. By uncovering its history, astronomers are also learning how common or unusual galaxies like ours may be, and how the conditions for stars and planets emerge across the universe.

This research shows that the Milky Way was not born in quiet isolation but shaped by violence, collisions, and rapid change. It reveals that stability is something galaxies earn over time, not something they start with. By tracing this transformation, scientists gain vital insight into when galaxies settle into disks, how long their turbulent phases last, and what physical processes drive these transitions.

In the end, this study does something profoundly human. It turns the Milky Way from a static backdrop into a living story, one that began in chaos and grew toward order. And by reading that story written across billions of years and hundreds of galaxies, we come a little closer to understanding our own place in the universe.

More information: Vivian Yun Yan Tan et al, Resolved Mass Assembly and Star Formation in Milky Way Progenitors since z = 5 from JWST/CANUCS: From Clumps and Mergers to Well-ordered Disks, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae0ffe