It began as a faint, restless signal buried in radio data from the southern sky. To most eyes, it might have looked like background noise, another whisper among countless cosmic murmurs. But to astronomers studying the universe with the Australian SKA Pathfinder telescope, this flicker carried a rhythm too precise, too insistent, to ignore. Somewhere about 7,000 light years away, something was spinning at extraordinary speed, sending out pulses like the ticking of a clock forged from collapsed stars.

This was not just another pulsar. It was something more dramatic, more volatile, and more intimate. It was a member of a rare and extreme family known as spider pulsars, systems where a dead star and a living companion are locked in a tight and violent dance.

By following that signal through layers of data, astronomers uncovered a new millisecond pulsar now known as PSR J1728−4608. Its discovery, reported in a paper published Dec. 10 on the arXiv pre-print server, adds a vivid new chapter to the story of how stars can survive, transform, and sometimes consume one another.

Listening Closely to the Fastest Heartbeats in the Universe

Millisecond pulsars are among the fastest-spinning objects known. They rotate hundreds of times every second, with periods below 30 milliseconds, and their pulses sweep past Earth with astonishing regularity. These objects are neutron stars, the dense remnants left behind after massive stars exhaust their fuel and collapse. But their incredible speed is not something they are born with. It is learned.

Astronomers believe millisecond pulsars form in binary systems. After the more massive star becomes a neutron star, it begins to draw matter from its companion. As material falls onto the neutron star, it transfers angular momentum, spinning the star up like a cosmic top wound tighter and tighter over time. What emerges is a pulsar with a heartbeat measured in milliseconds.

Among these already extreme objects, spider pulsars stand apart. They are binary systems in which the pulsar’s radiation and particle winds interact so strongly with the companion star that the companion becomes distorted, eroded, and in some cases slowly destroyed. The name is more than poetic. Like spiders, these pulsars trap their companions in close orbits and feed off them.

A Signal That Spoke of Motion and Shadows

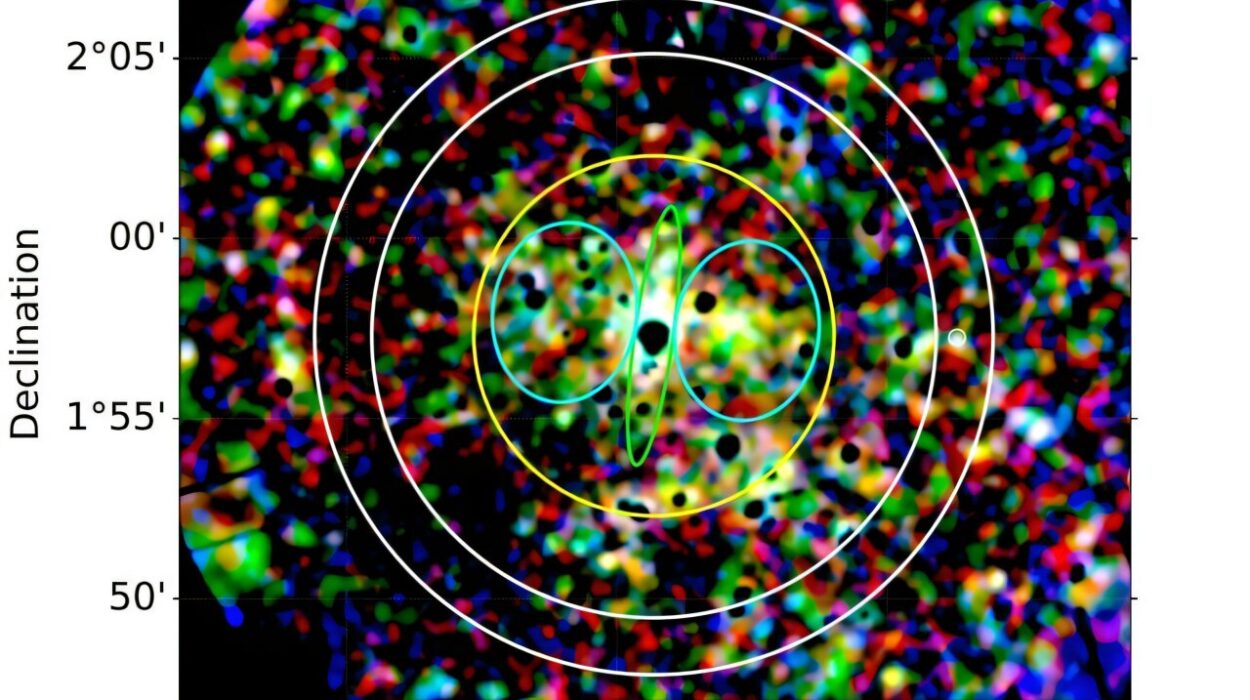

The story of PSR J1728−4608 unfolded through careful analysis of data from two large ASKAP surveys: the Evolutionary Map of the Universe and the Variables and Slow Transients Survey. Within these vast datasets, astronomers noticed that a source labeled VAST J172812.1−460801 was not steady. It pulsed.

When the team examined the signal more closely, the nature of the source became clear. As the researchers described it, “We detected a 2.86 ms pulsar-like signal at DM of 65.6 pc/cm3, accompanied by a measurable acceleration—indicative of binary motion, likely within an eclipsing binary system. Hereafter, we refer to VAST J172812.1−460801 as PSR J1728−4608.”

That measurable acceleration was a crucial clue. It meant the pulsar was not alone. Its pulses were being subtly shifted by motion in an orbit, pulled back and forth by the gravity of a companion star. Even more intriguingly, the system appeared to be eclipsing, with the pulsar’s radio signal periodically blocked.

What emerged was the portrait of a fast-spinning neutron star locked into an intimate and turbulent relationship.

A Redback Reveals Itself

Spider pulsars come in two main varieties, defined by the mass of their companions. If the companion has an extremely low mass, less than 0.1 times the mass of the Sun, the system is called a black widow. If the companion is heavier, the pulsar earns the name redback.

Measurements showed that PSR J1728−4608 has a spin period of approximately 2.86 milliseconds and a dispersion measure of about 65.5 pc/cm3. More importantly, the neutron star orbits a semi-degenerate companion every 5.05 hours. The minimum mass of that companion was measured to be 0.13 solar masses.

That single number placed the system firmly in redback territory.

Redbacks are known for their dramatic interactions. Their companions are not yet reduced to skeletal remnants. They are heavier, larger, and more capable of responding to the pulsar’s relentless energy output. This makes redback systems dynamic and variable, their behavior changing over time in ways that astronomers are still working to understand.

PSR J1728−4608 turned out to be no exception.

When the Pulses Disappear Into a Stellar Fog

One of the most striking features of PSR J1728−4608 is how often it vanishes from view. At a radio frequency of 888 MHz, the pulsar is eclipsed for 42% of its orbit. For nearly half of each 5.05-hour cycle, its rapid pulses are swallowed, not by distance, but by material within its own system.

During these eclipses, astronomers detected an excess in dispersion measure of about 2.0 pc/cm3. This suggests that additional ionized material lies along the line of sight, altering the way radio waves travel through it.

To understand what was happening, the researchers modeled the eclipse mechanism. Their results pointed toward synchrotron absorption as the dominant cause. In this scenario, energetic particles interacting with magnetic fields around the system absorb the pulsar’s radio emission, creating a temporary radio blackout.

The eclipses are not mere interruptions. They are evidence of an active environment, shaped by the pulsar’s energy and the companion star’s response, where plasma and magnetic fields swirl and evolve.

An Orbit That Will Not Sit Still

As astronomers continued to study PSR J1728−4608, they noticed another layer of complexity. The orbit itself was changing. The system exhibits orbital period variability, including a significant first-order orbital period derivative.

This kind of variability has been seen in other redback pulsars, and it hints at deeper physical processes unfolding within the companion star. The researchers assume that the changing orbit is likely caused by variations in the companion’s gravitational quadrupole moment.

In simpler terms, the companion star may be changing shape over time. As it becomes distorted, perhaps by rotation, tidal forces, or internal processes driven by the pulsar’s influence, its gravitational field changes slightly. These subtle shifts are enough to alter the timing of the orbit, producing measurable variations.

The result is a system that is alive with motion, never quite settling into a perfectly stable rhythm.

A Visible Companion in the Dark

While the pulsar itself is detected through radio waves, the companion star reveals its presence in visible light. The study identified an optical counterpart within 0.5 arcseconds of the radio position of PSR J1728−4608.

This counterpart has a mean G-band magnitude of 18.8 mag, faint but measurable. More telling is its light curve, which shows variations consistent with ellipsoidal modulation and irradiation effects.

Ellipsoidal modulation suggests that the star is stretched into an elongated shape by the gravitational pull of the neutron star. Irradiation effects point to heating of the companion’s surface by the pulsar’s intense emission. Together, these signatures paint a picture of a star under stress, reshaped and illuminated by its compact partner.

It is a rare glimpse into a relationship where one object is both sculptor and destroyer.

Why This Discovery Matters

The discovery of PSR J1728−4608 is not just the addition of another name to a catalog. It is a new laboratory for understanding some of the most extreme interactions in the universe. Redback pulsars sit at a crossroads of stellar evolution, binary dynamics, plasma physics, and relativistic phenomena.

By studying systems like this, astronomers can learn how millisecond pulsars are formed and how they continue to evolve. The eclipses reveal the behavior of matter under intense radiation and magnetic fields. The orbital variability offers clues about how stars respond structurally to prolonged external forces. The optical counterpart connects radio observations to visible changes in a living star.

PSR J1728−4608 reminds us that even in the depths of space, far from Earth, there are systems in constant negotiation, shaped by gravity, energy, and time. Each new spider pulsar discovered sharpens our understanding of how stars live together, feed off one another, and change the fabric of their surroundings.

In the quiet ticking of a 2.86-millisecond heartbeat, astronomers have found another story of cosmic intimacy, one that continues to unfold with every orbit.

More information: F. Petrou et al, Discovery of the redback millisecond pulsar PSR J1728-4608 with ASKAP, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.09339