Cancer drug resistance is often described as if a tumor simply hardens itself against therapy. But scientists studying pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma at the University of Virginia suspected something far more intricate was taking place. To them, resistance was not a wall but a conversation, a coded exchange unfolding inside cancer cells. If they could decode that language, perhaps they could learn how to interrupt it.

Their new work, published in Science Signaling, reveals just how deep that conversation goes. What they found was not only the signaling pathway they had long been hunting but a hidden molecular accomplice quietly sustaining drug resistance in one of the world’s deadliest cancers.

Into the Maze of a Shape-Shifting Cell

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common form of the disease, affecting up to 90 percent of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. It often appears late, spreads early, and resists nearly every drug sent to stop it. No matter where patients live or how they receive treatment, drug resistance remains a universal obstacle.

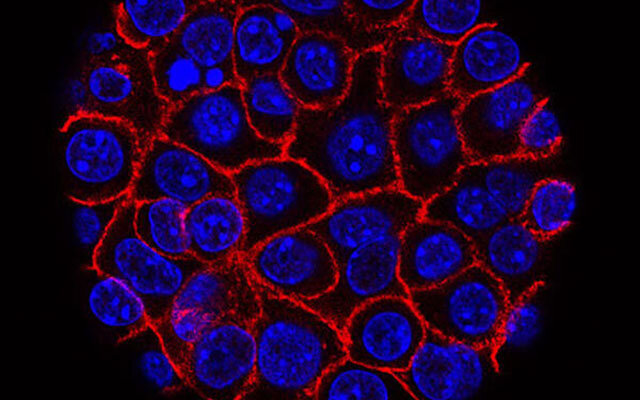

In this cancer, cells rarely stay in one form. They blur and reshape, shifting identities in a process known as the epithelial mesenchymal transition, or EMT. Dr. Michelle Barbeau, the lead author of the team’s analysis, explains it plainly. Signaling molecules, she reports, spur a complex event known as EMT. Under their influence, stationary, orderly epithelial cells transform into long, invasive, spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells. And with that transformation comes resistance.

EMT does not simply make cancer cells harder to kill. It helps them escape entirely. Affected cells ramp up efflux pumps that push chemotherapy drugs back out, ejecting medicine meant to save a patient’s life.

But EMT itself is slippery, shifting, dynamic. The Virginia team knew it could not be happening in isolation. Something had to be pulling the strings.

A Mathematical Compass in a Biological Storm

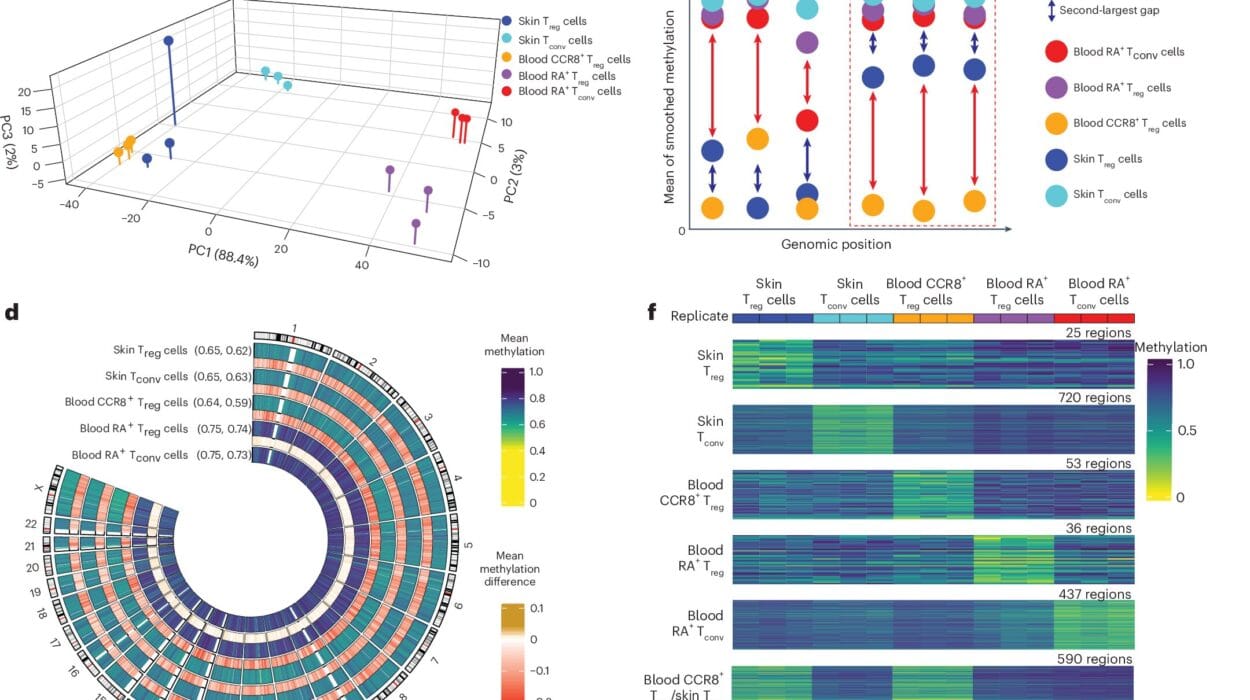

To find that hidden force, the researchers turned to an unexpected tool. They relied on information theory, a branch of applied mathematics that usually speaks the language of signals, networks, and data. Here, it served as the team’s compass inside the chaos of molecular activity.

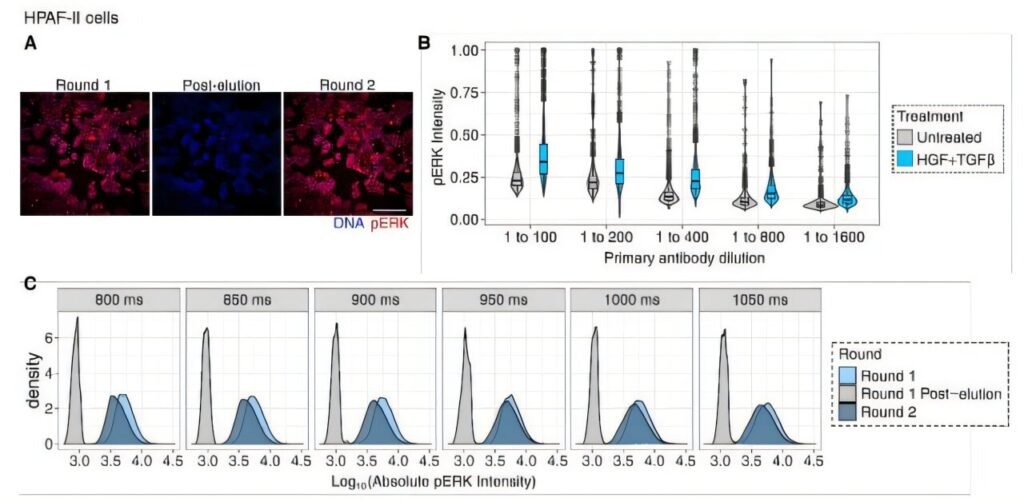

What they sought was a measure called mutual information. It allowed them to see, with unusual clarity, which molecules were truly driving EMT and which were simply part of the noise.

Their calculations pointed again and again to the same signal.

“The dominant role of ERK was consistently indicated by mutual information,” wrote Barbeau, an experimental pathologist.

ERK, a kinase enzyme, was more than a participant. It appeared to be central to activating EMT. Yet even this discovery came with a twist.

Decoding the Signal at the Level of a Single Cell

Using imaging, calculations, and animal models, the team traced ERK’s influence down to individual cells. That level of detail brought something startling into focus. EMT was not uniform. It did not sweep through a tumor like a single wave. Instead, it rippled, faltered, surged, and stalled unevenly across a diverse cellular landscape.

“Epithelial-mesenchymal transition occurs heterogeneously among carcinoma cells to promote chemoresistance,” Barbeau wrote.

In other words, cancer cells do not undergo EMT together. They exist in every possible state at once. Some cling to their epithelial shape. Some fully adopt the mesenchymal spindle form. Others occupy a mysterious in-between, a hybrid form that is neither fully stationary nor fully migratory. The result is a mosaic of behaviors that makes tumors resilient, unpredictable, and extremely difficult to treat.

Those cells that do complete the transition carry a terrible advantage. They become invasive, drug resistant, and disturbingly durable—“as close to immortal as a cancer cell can get.”

When One Pathway Fails, Another Steps In

The Virginia researchers pressed further. If ERK was so essential to EMT, what would happen if they blocked it?

In the lab, they inhibited ERK—and watched as something unexpected happened. Another kinase, JNK, stepped forward to continue signaling EMT. ERK and JNK did not work alone. Growth factors also shaped whether EMT switched on, meaning each tumor cell encountered its own unique blend of influences. This only increased the heterogeneity already haunting pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

And with that rise in heterogeneity came a darker truth. Barbeau and colleagues discovered that the more diverse the EMT states within a tumor, the worse the patient’s outcome tended to be.

A Cancer That Moves Like Smoke

As the story unfolded, it became clear just how elusive pancreatic cancer can be. EMT enables tumor cells to become more metastatic, to spread and seed new tumors across the body. In their epithelial form, cancer cells multiply rapidly. In the spindle-shaped mesenchymal form, they wander unpredictably. EMT can even generate cancer stem cells, dangerous entities that resist many chemotherapeutic agents.

It is a transformation that makes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma both deadly and difficult to stop. Its global toll is immense. Roughly 500,000 people are diagnosed each year, and nearly as many die, a reflection of a disease in which drug resistance is not an exception but a rule. Five-year survival rates hover around 10 to 13 percent, improving only when the cancer is caught early—a rarity, given the lack of screening tests and the vague nature of early symptoms.

In this context, understanding EMT is not an academic exercise. It is a matter of life and death.

Toward a Future Where Signals Can Be Silenced

Yet this research does more than describe a grim biological process. It offers hope. By identifying the signaling pathways responsible for EMT, and by untangling how ERK and JNK sustain drug resistance, the team has begun sketching the outline of a vulnerability.

“Identifying the signaling pathways involved [in EMT] will nominate drug combinations to promote chemoresponse,” Barbeau asserted.

If ERK is central to the onset of EMT, then inhibiting it could help prevent cancer cells from transforming into their most dangerous form. The authors concluded that adding ERK inhibitors to existing treatments for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma could reduce EMT driven resistance, potentially improving patient outcomes.

Why This Research Matters

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most lethal diseases on Earth, not because it spreads faster than other cancers but because it becomes untreatable with shocking efficiency. Drug resistance is its shield, EMT its engine. By decrypting the signaling pathways that power this transformation, the University of Virginia team has illuminated a path that scientists and physicians can now explore with new clarity.

This work matters because it reveals that resistance is not inevitable. It is orchestrated. It is signaled. And what is signaled can, in time, be silenced.

The discovery of ERK’s dominant role, the backup behavior of JNK, and the profound influence of EMT heterogeneity gives cancer researchers something they have long needed: a molecular map of where resistance begins.

And every map, no matter how complex, is ultimately a guide toward finding a way through.

More information: Michelle C. Barbeau et al, The kinase ERK plays a conserved dominant role in the heterogeneity of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells, Science Signaling (2025). DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.ads7002