The story begins with a beam of light so small and so precise that it can slip into a single cell and change what that cell does. Researchers from the University of Geneva, working alongside colleagues in Switzerland, France, the United States and Israel, describe how this ability to guide cells with light is no longer just a laboratory dream. It is already shaping neuromodulatory therapies and even the first human retinal interventions for blindness. Their Perspective article, “Roadmap for direct and indirect translation of optogenetics into discoveries and therapies for humans,” published in Nature Neuroscience, sets the stage for a scientific frontier where light does not merely illuminate the world but actively rewrites how we sense and respond to it.

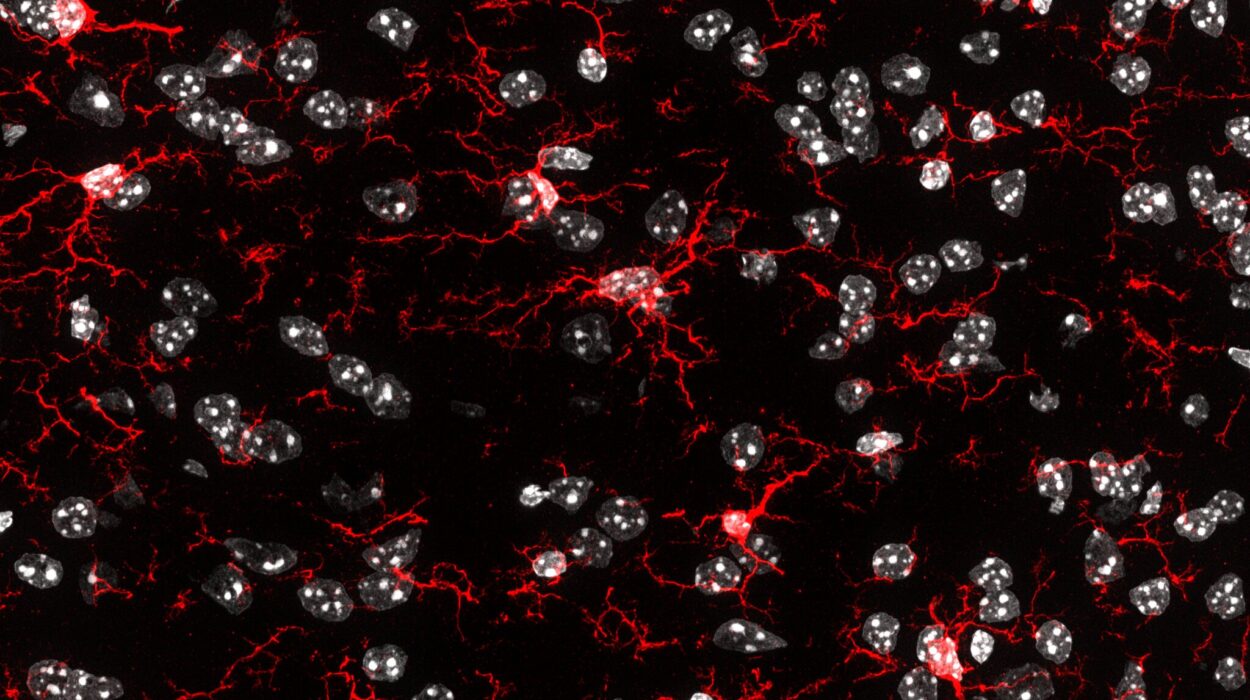

Optogenetic control uses light to impose precise gain or loss of function in specific cell types, sometimes even individual cells. These can be chosen by their location, their connections, their gene expression or combinations of these features. This level of selectivity has given scientists something they have never had before: a way to investigate the living brain with exquisite control, turning cells on or off with millisecond timing. The technique has grown into a flexible toolbox ranging from implanted fiber optics to three-dimensional holographic illumination of neuronal ensembles and even wearable LEDs that can act noninvasively.

Because the effects can shift with a simple change in light intensity and can be as brief as a heartbeat or as long-lasting as a chronic therapy, optogenetics has broadened far beyond its origins. More than ten thousand studies have now used optogenetic tools not just in neuroscience but in other organs, leading to modern explorations of memory, decision-making, heart-to-brain communication and circuit-level functions that extend well beyond any single disease.

Causal Trails Through the Wilderness of the Brain

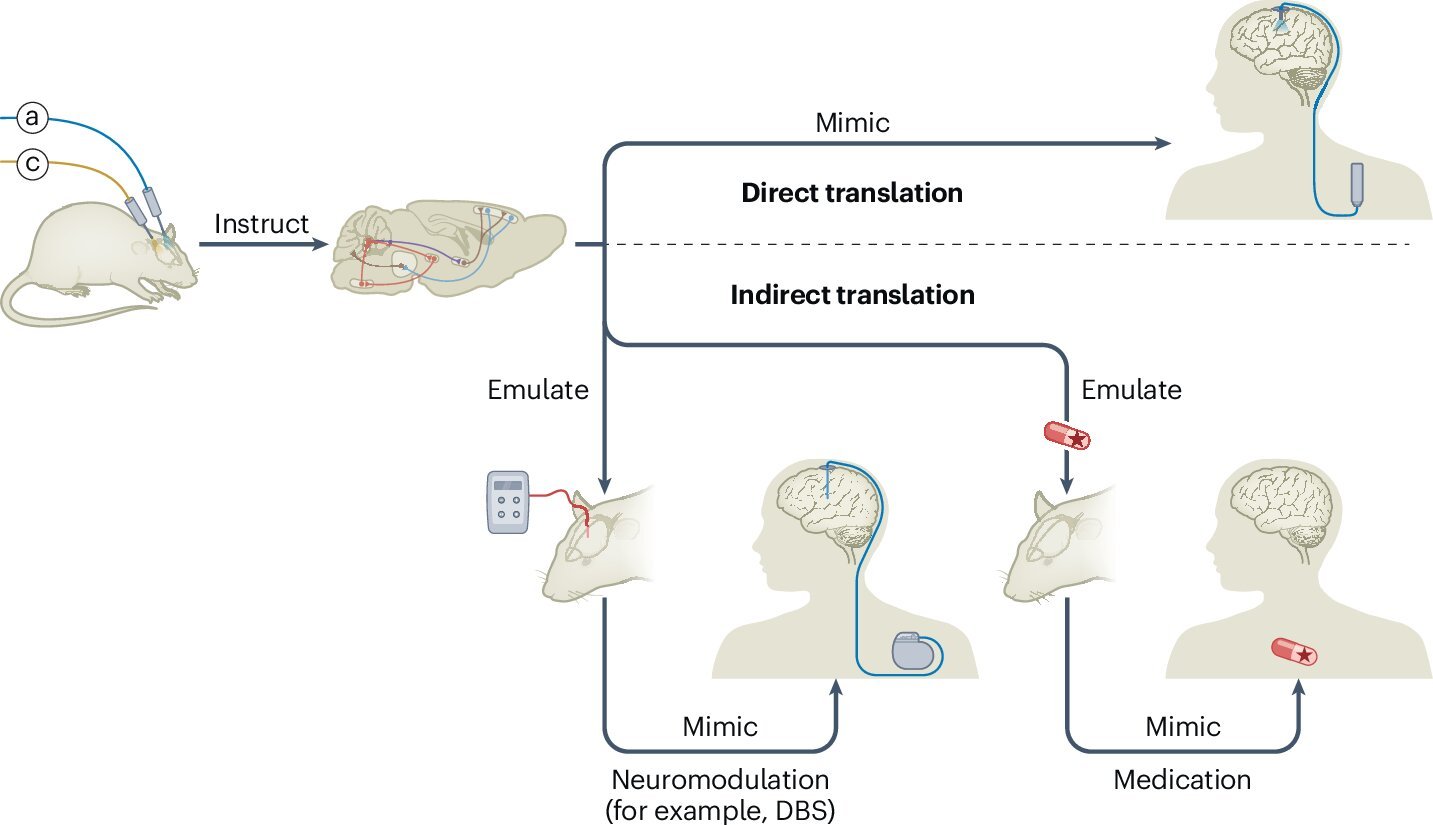

The scientists’ roadmap describes two routes from basic optogenetic discovery to clinical therapies. Both begin with a simple but profound ability: finding and testing causal links between specific cells and behaviors.

In the first route, causal circuit experiments identify the precise populations of cells responsible for particular neuropsychiatric symptoms. Once these cells are mapped in detail—by their location, their gene expression and their connections—therapies can be guided toward these targets without requiring patients to receive genes or light directly. This is where technologies like deep brain stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation and MRI-guided focused ultrasound come into play. Each of these methods can be redirected by optogenetic findings, using the circuit maps as a compass to locate and influence the right neural populations.

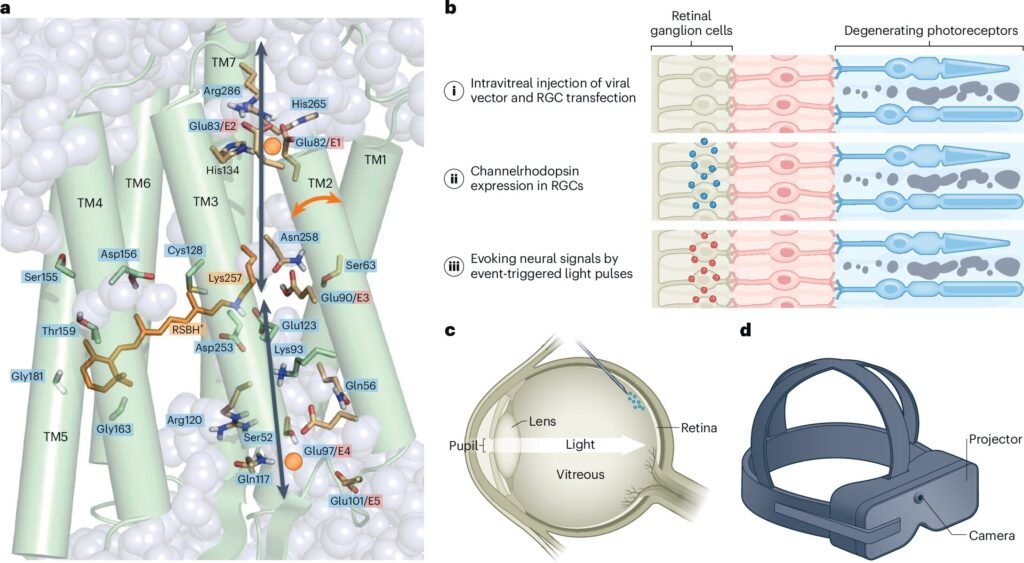

The second route moves closer to direct optogenetic therapy by producing more detailed descriptions of human brain function that may guide new treatments. Here the retina provides a remarkable early example. Delivery of a channelrhodopsin gene and light to the retina of a blind patient with retinitis pigmentosa significantly improved visual perception, becoming a landmark in the field. Nine patients treated in similar ways have shown no safety concerns so far, and at least four more clinical trials are underway. Each trial tests optogenetic vision restoration in different retinal cell types, revealing which parts of the visual system can be brought back into the light.

The Possibility Hidden Inside Symptoms

The researchers emphasize that common neuropsychiatric disorders are often collections of symptoms woven through patterns of circuit activity. Optogenetic mapping has experimentally traced symptoms such as anhedonia, compulsive behavior, social motivation and social cognition deficits, anxiety, post-traumatic stress reactions and psychosis back to specific circuits.

These findings matter because circuits can be influenced. Conditions like essential tremor, focal epilepsies, Parkinsonian motor control, end-stage retinitis pigmentosa and some forms of deafness have all shown experimental promise for circuit-directed interventions. In these cases, light-guided discoveries reveal which parts of the system need help and how they might respond.

Other conditions may be even more amenable to direct optogenetic therapy. Peripheral neuropathy, ALS, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, complex regional pain syndrome and bladder or bowel dysfunction after spinal injury all affect regions outside the brain, making them more accessible to gene and light therapy. These are conditions where current treatments fall short and where optogenetics might have room to do what other methods cannot.

When Light Meets Risk

The researchers also confront the reality that clinical optogenetics belongs to the broader world of gene therapy and inherits its risks. Viral vectors, which deliver the necessary genes into cells, can provoke local immune reactions inside brain tissue through microglial activation. They can also produce systemic innate and adaptive responses that affect the liver, blood vessels or other organs, especially when doses are high. Safety concerns focus on these immune responses, inflammation in nervous system tissue and the ongoing challenge of establishing safe dose limits.

Regulatory oversight adds another layer. Optogenetic therapies are treated as combinations of a biological product and a medical device. This means that retinal goggles, implantable or skull-mounted LEDs and modified deep brain stimulation leads must meet device quality and performance standards, while the gene therapy components must satisfy safety and dosing requirements. Every piece of the intervention must align with regulations that protect patients from avoidable risk.

The Ethical Edge of Light

The ethical landscape is equally complex. The ability of optogenetics to alter mood, motivation, memory and fundamental survival drives—hunger, thirst, fear, aggression, mating and parenting—raises questions that go beyond medicine. The researchers highlight cognitive liberty, the right to mental self-determination, as a central ethical principle. This supports offering optogenetic interventions for severe diseases when existing treatments fail, but it also demands caution.

Neural data privacy introduces another frontier. As devices interface more closely with the nervous system, brain-related cybersecurity becomes essential. Protecting sensitive neural information and maintaining patient autonomy will be crucial as researchers explore interventions that lead into previously uncharted territory.

Why This Research Matters

The roadmap described by the researchers is more than a technical plan. It marks a turning point in how we understand and treat the nervous system. Optogenetics offers a level of precision that no previous method has matched. It can reveal exactly which cells contribute to symptoms, guide existing neuromodulation technologies and open the door to new treatments for blindness and potentially many other conditions.

At the same time, the field stands at a crossroads. Safety, regulation and ethics will shape how far optogenetics can go and how many people it can help. The work described in the Perspective article shows that we are no longer asking whether light can change human neural function. That question has been answered. Now we are asking how to use that power wisely, how to protect the people who need it and how to chart a future in which the brain’s deepest circuits can be guided without losing sight of human dignity and care.

This matters because millions of people live with conditions rooted in the circuits of the nervous system, and many have exhausted the treatments available today. Optogenetics offers a chance not only to understand the brain but to restore its lost functions, relieve suffering and illuminate paths that were once closed. The researchers’ roadmap is a reminder that scientific possibility is brightest when paired with responsibility, and that even the smallest spark of light can change everything when it reaches the right cell.

More information: Christian Lüscher et al, Roadmap for direct and indirect translation of optogenetics into discoveries and therapies for humans, Nature Neuroscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02097-9