In today’s modern world, we are surrounded by invisible battles. While we’ve made extraordinary strides in curing physical diseases, there remains a realm of human suffering often misunderstood, stigmatized, and overlooked: mental illness.

Mental illness is not a failure of character, willpower, or morality. It is not a weakness, nor a flaw in personality. It is a genuine, biological, psychological, and often sociocultural phenomenon—one that affects millions across the globe. From anxiety disorders to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder to PTSD, mental illnesses alter perception, cognition, emotion, and behavior. They change lives—sometimes subtly, sometimes catastrophically.

This article explores mental illness through the lens of medical science. We’ll dive into how it begins, what causes it, how the brain plays a central role, and how modern medicine is working toward better treatments. We will also touch on the cultural dimensions and what the future may hold for the mental health movement.

What Is Mental Illness?

At its core, mental illness refers to conditions that disrupt a person’s thinking, feeling, mood, ability to relate to others, and daily functioning. These conditions exist on a spectrum—from mild anxiety to debilitating psychosis. They are diagnosable, treatable, and real.

Medical science classifies mental disorders using internationally recognized systems like the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and the ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases). These manuals list criteria based on clusters of symptoms, allowing clinicians to assess and treat disorders with consistency.

Some of the most commonly diagnosed mental illnesses include:

- Depression

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia

But what causes these conditions? Is it the brain, the environment, our upbringing, or our genetics?

Science says: it’s all of the above.

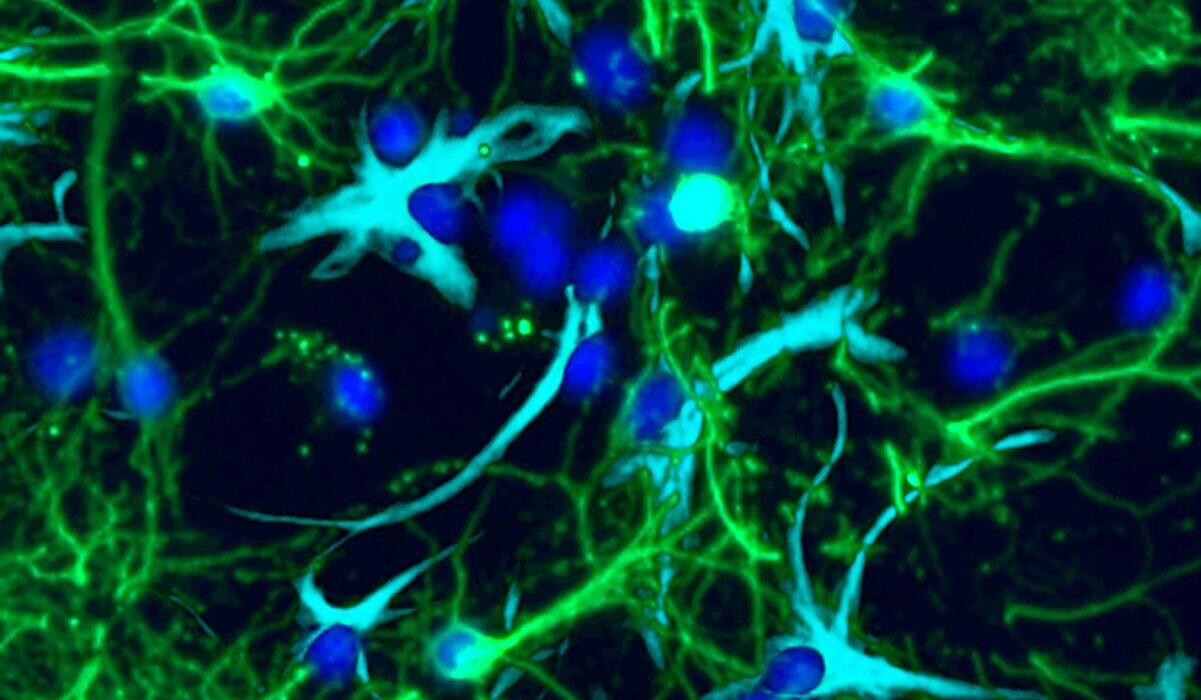

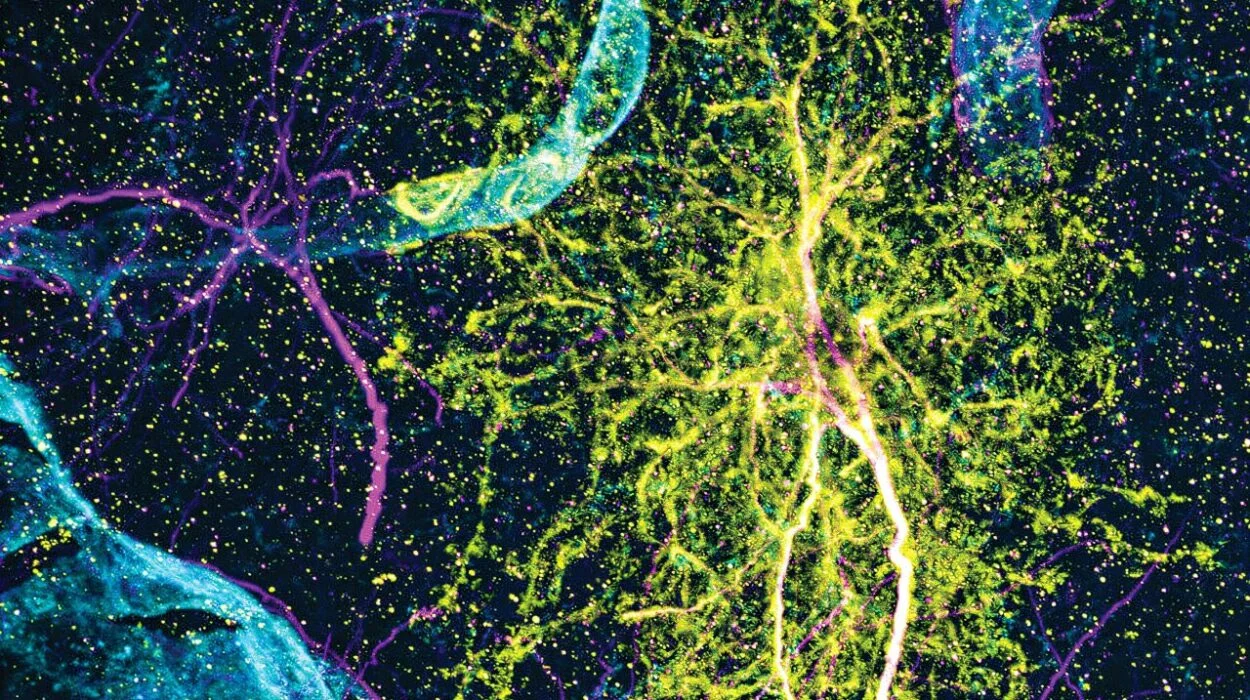

The Brain and Mental Illness: A Neurological Landscape

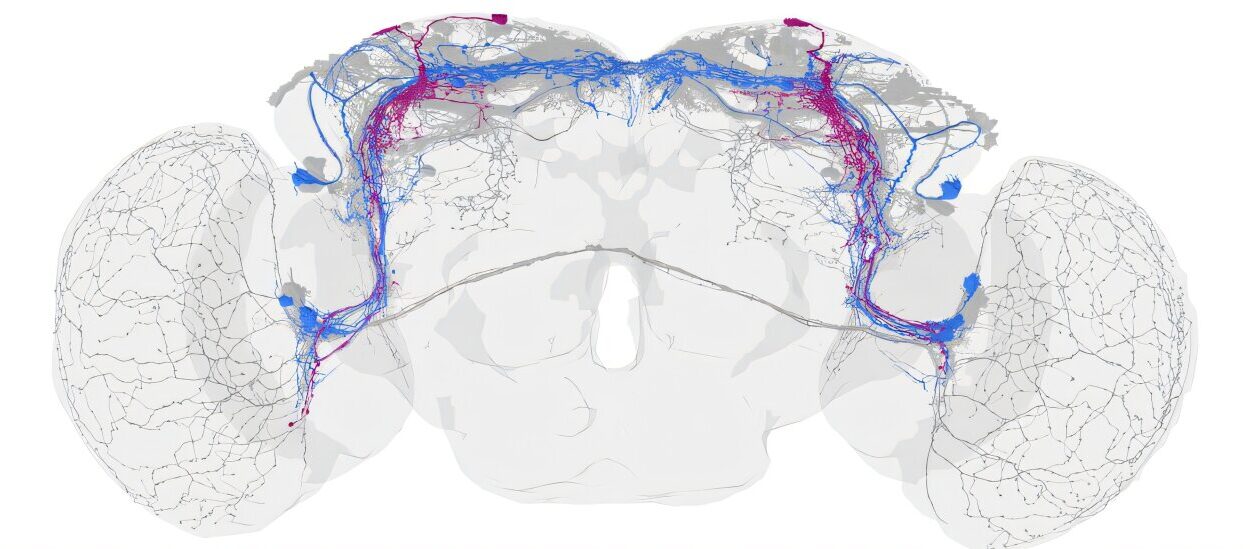

Mental illness is fundamentally linked to the brain—the most complex organ in the known universe. Our brains are made up of nearly 86 billion neurons, which communicate via electrical impulses and chemical signals. These chemical messengers—called neurotransmitters—are essential for how we feel, think, remember, and react.

When mental illness strikes, it’s often because something in this intricate communication system goes wrong.

Take depression, for instance. Research shows that people with major depressive disorder may have low levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood, sleep, and appetite. Dopamine and norepinephrine imbalances are also involved, affecting pleasure, motivation, and alertness.

In anxiety disorders, heightened activity in the amygdala—the brain’s fear center—can lead to persistent states of tension, dread, or panic, even when there is no immediate danger.

Schizophrenia, one of the most severe mental illnesses, is associated with excess dopamine activity in certain brain regions, disrupted glutamate signaling, and abnormalities in brain structure and connectivity.

Modern brain imaging techniques like fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) and PET (positron emission tomography) allow scientists to observe these changes in real-time, comparing brain activity in healthy individuals versus those with mental illnesses.

But while the brain is a central player, it doesn’t act alone.

The Role of Genetics: Inheriting Risk

Genes are the body’s instruction manual, telling cells how to function, including those in the brain. Mental illnesses often run in families, suggesting a genetic component. If a parent has bipolar disorder, for example, a child has a higher chance of developing it too.

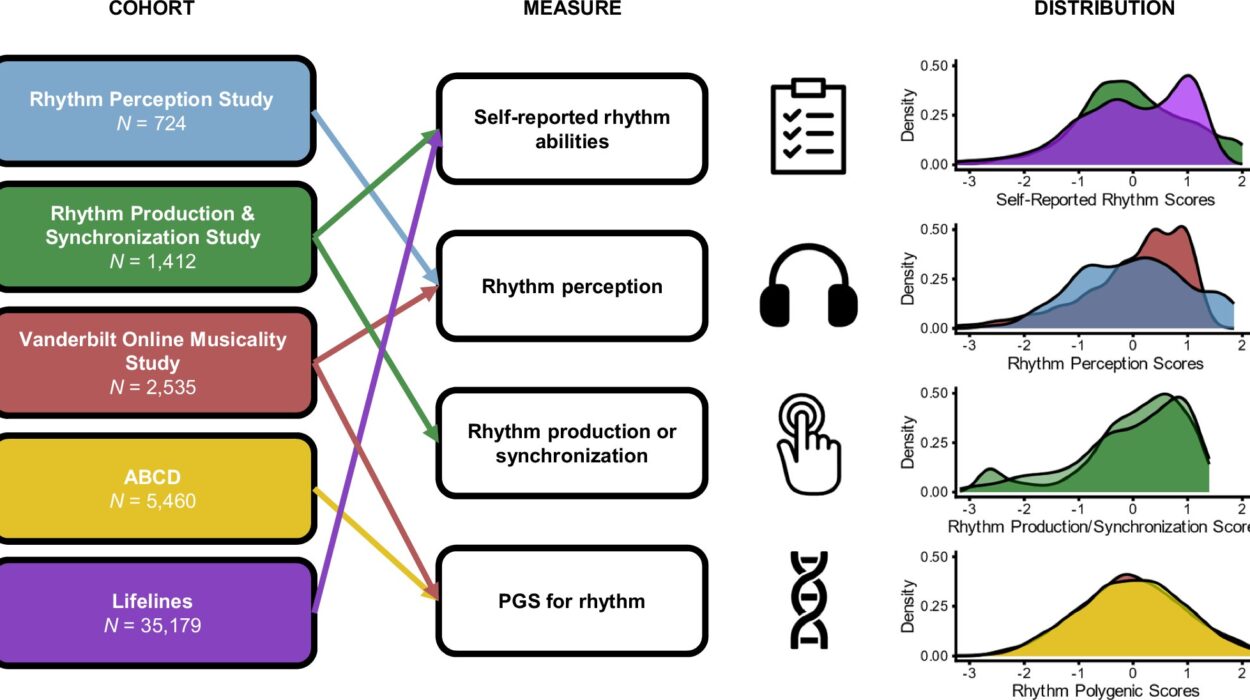

But there is no single “mental illness gene.” Instead, there are hundreds—possibly thousands—of genetic variants, each contributing a small amount to overall risk. This makes mental illness a polygenic condition, much like height or intelligence.

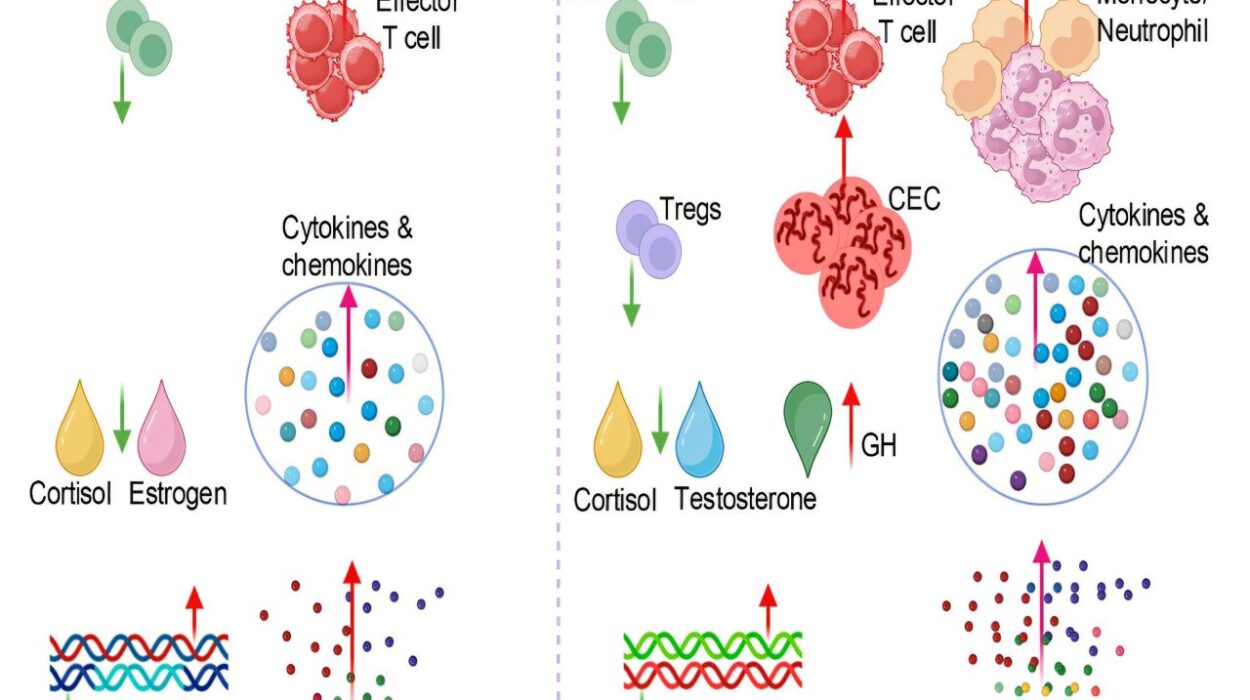

Recent advances in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified specific genes linked to schizophrenia, major depression, and autism spectrum disorders. Some of these genes influence brain development, immune function, and even how neurons communicate.

However, having these genes does not guarantee a person will develop a mental illness. Instead, genes set the stage, and environment provides the script.

Environmental Triggers: When Life Impacts the Mind

The phrase “nature versus nurture” is outdated. Today, scientists speak of nature interacting with nurture—a dynamic, ever-changing dance between biology and experience.

Early-life trauma, chronic stress, abuse, neglect, war, poverty, or substance use can all activate or worsen mental health issues. The developing brain, particularly in childhood and adolescence, is highly sensitive to environmental influences.

Prolonged exposure to stress—whether emotional, financial, or physical—floods the body with cortisol, the stress hormone. When stress is short-term, cortisol helps us survive. But when it becomes chronic, it begins to harm the brain, especially areas like the hippocampus (which regulates memory) and the prefrontal cortex (responsible for decision-making and emotional regulation).

Trauma, especially in childhood, can cause lasting changes in brain circuitry and stress-response systems, increasing vulnerability to mood disorders, personality disorders, and substance abuse.

Substance use is another environmental risk factor. Psychoactive drugs can cause or exacerbate mental illnesses by altering brain chemistry. Methamphetamine and cocaine can induce psychosis; alcohol abuse often coexists with depression and anxiety; cannabis, especially high-THC strains, may trigger symptoms of schizophrenia in genetically vulnerable individuals.

Societal factors—like discrimination, isolation, and lack of access to care—can also worsen outcomes and increase risk, especially in marginalized communities.

Diagnosis: The Challenge of Seeing the Invisible

Diagnosing mental illness is both an art and a science. Unlike physical illnesses that may show up on X-rays or blood tests, mental illnesses manifest through behavior, mood, speech, cognition, and subjective reports.

Clinicians rely on structured interviews, patient histories, and standardized tests. Diagnostic criteria must be met for a certain duration and intensity before a label is given.

This process is not perfect. Mental illness symptoms often overlap. Depression may look like anxiety. Bipolar disorder may be misdiagnosed as ADHD or personality disorder. Cultural and language differences can mask or mimic symptoms.

Moreover, stigma causes many to underreport symptoms. Men may hide depression as anger or irritability. Young people may dismiss intrusive thoughts as normal. Elderly individuals may attribute cognitive changes to aging, not mental illness.

Accurate diagnosis requires time, empathy, and training. And even then, it can evolve. Some patients are misdiagnosed for years before receiving the right treatment.

Treatment: Managing the Mind

Treatment of mental illness varies widely depending on the disorder, its severity, and the individual’s needs. The most common approaches include:

Psychotherapy (Talk Therapy): Evidence-based psychotherapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), and trauma-focused therapy help patients understand their thoughts, manage emotions, and change behaviors. Therapy can be short-term or long-term and is often the first line of treatment for mild to moderate conditions.

Medication: Antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and anti-anxiety medications act on neurotransmitters to correct imbalances. While not cures, they can reduce symptoms, prevent relapses, and restore functionality. Medication works best when paired with therapy.

Lifestyle Changes: Regular exercise, healthy sleep, a nutritious diet, social support, and stress-reduction practices like mindfulness and meditation can significantly improve mental health. These lifestyle factors influence neurochemistry and reduce inflammation in the brain.

Hospitalization and Crisis Care: In severe cases, where individuals are suicidal, homicidal, or experiencing psychotic episodes, inpatient care provides safety, stabilization, and intensive treatment.

Community Support: Peer groups, support networks, rehabilitation centers, and community-based programs play a crucial role in long-term recovery, especially for chronic conditions.

Modern medicine is moving toward personalized psychiatry, tailoring treatments based on genetic, biological, and psychological profiles. Newer interventions, like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), ketamine infusions, and even psychedelic-assisted therapy, show promise in treatment-resistant cases.

The Stigma of Mental Illness: A Barrier to Healing

Despite decades of scientific progress, mental illness remains deeply stigmatized. Misconceptions—like equating schizophrenia with violence, or thinking depression is laziness—persist even among educated populations.

Stigma leads to shame, silence, and delay in seeking help. Many sufferers go years without treatment, fearing judgment or discrimination. Families may deny or hide illness due to cultural taboos. Insurance companies may offer inadequate mental health coverage, further reinforcing inequality.

Combatting stigma requires education, media responsibility, and open dialogue. Seeing mental illness as a medical condition—not a moral one—is the first step.

Famous figures sharing their struggles, from athletes to artists to presidents, has helped reduce stigma. But much work remains, especially in rural areas and developing countries, where resources are scarce and beliefs remain rigid.

Mental Illness in Children and Adolescents

The early years of life are foundational for mental health. Half of all mental illnesses begin by age 14, and three-quarters by age 24. Conditions like ADHD, autism, anxiety, and depression often manifest during childhood.

Early detection is crucial. Untreated mental illness can impair learning, social development, and long-term outcomes. But diagnosing children is complex—normal behavior varies widely by age and temperament.

Pediatric psychiatry must navigate family dynamics, school systems, and developmental stages. Treatments often involve parents, teachers, and therapists working together.

Adolescence adds new pressures: identity, peer relationships, academic expectations, and exposure to substances. The digital world compounds these challenges. Cyberbullying, social media comparisons, and online radicalization can all impact mental well-being.

Schools play a vital role in mental health support. So do pediatricians, community programs, and public awareness campaigns that emphasize early intervention and destigmatization.

Culture and Mental Illness: One Condition, Many Expressions

Mental illness is universal—but its expression is shaped by culture. Depression in the West may appear as sadness or despair. In East Asian cultures, it might manifest more as fatigue or physical complaints. In some African societies, schizophrenia may be seen as spiritual possession rather than illness.

Beliefs, language, and community norms influence whether people seek help, how they describe symptoms, and what treatments they accept.

This is why culturally competent care is essential. Mental health providers must understand their patients’ backgrounds to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure effective treatment.

Global health organizations like the WHO now emphasize context-sensitive models, blending Western medicine with indigenous healing, where appropriate, to address mental illness in culturally meaningful ways.

The Future of Mental Health: Where Science Is Headed

We are entering a new era of mental health science. Advances in neuroscience, genetics, and artificial intelligence promise earlier diagnosis, better treatments, and even prevention.

Neuroimaging may one day identify mental illness before symptoms appear. AI algorithms could predict suicide risk from online behavior or medical records. Digital therapeutics—apps that deliver CBT or mindfulness training—are becoming more sophisticated.

Ketamine and psychedelics like psilocybin and MDMA are being tested for treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and addiction, with promising results. These therapies may work by “resetting” neural pathways and facilitating emotional breakthroughs.

Precision psychiatry, using biomarkers and personalized data, aims to match patients with the most effective treatment from the start—rather than relying on trial and error.

But the future also demands equity. Global access to mental healthcare remains deeply unequal. Rural areas, war zones, and low-income communities still face shortages of professionals and resources.

To address the mental health crisis globally, we must not only advance science—but also ensure compassion, access, and justice.

Conclusion: Understanding the Human Mind

Mental illness is not someone else’s problem. It touches every family, every nation, every age group. It is part of the human condition—complex, painful, and deeply intertwined with who we are.

Science offers hope. The brain is no longer a black box. We are beginning to understand how thoughts, emotions, genes, and environment interact. We are developing better tools, better drugs, and better ways to talk about suffering.

But science alone is not enough.

To truly confront mental illness, we must listen. We must support. We must stop treating mental health as an afterthought and make it a central pillar of healthcare, education, and society.

Because when we heal the mind, we don’t just treat illness.

We restore dignity.

We reclaim lives.

We rediscover our shared humanity.