Imagine waking up each day not knowing whether your gut will be your ally or your enemy. For millions of people around the world, this is the reality of living with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). On the outside, they may look perfectly fine, but inside their digestive system feels like a battlefield—unpredictable cramps, bloating, urgent trips to the bathroom, or sometimes the complete opposite: days without relief. IBS is not life-threatening, but it can be life-altering, shaping daily choices, diets, social plans, and even emotional well-being.

The frustrating part? IBS is a condition without a clear “one-size-fits-all” explanation. It is a complex interplay of the gut, brain, and environment, making it both fascinating and maddening to understand. To truly grasp IBS, we need to explore not just the physical symptoms but also the psychological impact, the science of the gut-brain connection, and the growing body of research that is slowly unraveling its mysteries.

What Is Irritable Bowel Syndrome?

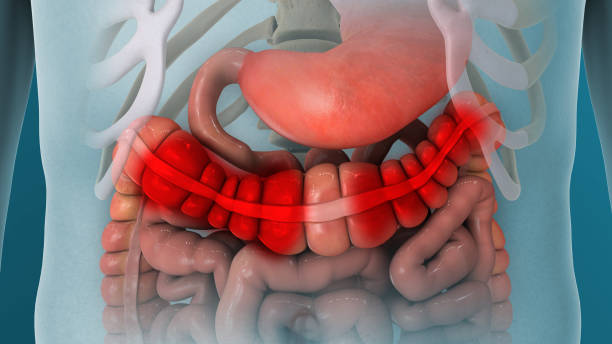

Irritable Bowel Syndrome is a chronic disorder of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, particularly the large intestine, characterized by recurring abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits. It is categorized as a functional gastrointestinal disorder, meaning the digestive tract looks normal under tests like colonoscopy, but it doesn’t function normally.

Globally, it is estimated that 10–15% of the population suffers from IBS, though many cases remain undiagnosed. Women are more likely than men to be affected, and symptoms often begin in late adolescence or early adulthood. Despite its prevalence, IBS is still misunderstood, sometimes dismissed as “just stress” or “just diet-related,” which only adds to the stigma and emotional burden carried by patients.

The Science of the Gut-Brain Connection

To understand IBS, we must look beyond the intestines themselves. The gut and brain are intimately connected through what scientists call the gut-brain axis. This communication system involves the nervous system, hormones, immune cells, and even trillions of microbes living in our intestines.

In a healthy person, the gut and brain work in harmony: the gut digests food, absorbs nutrients, and communicates with the brain about hunger, satiety, and potential threats. But in IBS, this system becomes hypersensitive. The nerves in the gut overreact to normal digestive processes, sending exaggerated pain signals to the brain. Meanwhile, stress, anxiety, or emotional disturbances can amplify the gut’s response, creating a feedback loop that worsens symptoms.

Emerging research highlights the role of the gut microbiome—the diverse community of bacteria and microorganisms in the intestines. People with IBS often show imbalances in these microbes, which may contribute to inflammation, gas production, and altered bowel movements. This microbial influence is one of the most exciting frontiers in IBS research.

Causes of IBS: Untangling a Complex Web

IBS does not have a single cause. Instead, it arises from a combination of factors that disrupt the delicate balance of the digestive system. Some of the most studied contributing elements include:

Abnormal Gut Motility

In IBS, the muscles of the intestine may contract too quickly or too slowly. Rapid contractions can cause diarrhea, while sluggish contractions can lead to constipation. Both can trigger cramping and discomfort.

Hypersensitivity of the Gut

People with IBS have an enhanced sensitivity to pain signals from the intestines. Normal amounts of gas or stool movement, which would not bother most individuals, can cause significant pain in those with IBS.

Altered Microbiome

Research shows differences in the gut bacteria of IBS patients compared to healthy individuals. Some may have fewer “good bacteria” and more gas-producing microbes, contributing to bloating and discomfort.

Post-Infectious Changes

For some people, IBS begins after a severe bout of gastroenteritis or food poisoning. This is known as post-infectious IBS, and it may be linked to lingering inflammation or changes in the gut microbiome after infection.

Psychological and Emotional Factors

Stress, anxiety, and depression are not causes of IBS, but they strongly influence its severity and frequency. The brain and gut are so interconnected that emotional distress can manifest as digestive symptoms.

Food Sensitivities

Certain foods, especially those high in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs), can worsen IBS symptoms. These foods produce gas during digestion, leading to bloating, pain, and altered bowel movements.

Types of IBS

Doctors often categorize IBS based on the predominant bowel habit:

- IBS-D (Diarrhea-predominant): Frequent loose stools, urgency, and abdominal discomfort.

- IBS-C (Constipation-predominant): Hard, infrequent stools often accompanied by straining.

- IBS-M (Mixed type): Alternating between constipation and diarrhea.

- IBS-U (Unclassified): Symptoms do not fit neatly into the other categories.

Understanding which type a person has is crucial for tailoring treatment, since strategies for IBS-D may not help someone with IBS-C.

Symptoms of IBS

IBS manifests in a variety of ways, but its hallmark is abdominal pain associated with changes in bowel habits. Symptoms can range from mild inconvenience to severe disruption of daily life.

Common Symptoms

- Abdominal cramping or pain, often relieved by a bowel movement

- Bloating and excessive gas

- Diarrhea, constipation, or both

- Urgency or a feeling of incomplete evacuation after using the bathroom

Additional Symptoms

- Mucus in the stool

- Fatigue and sleep disturbances

- Nausea, especially after meals

- Increased urinary frequency in some cases

Importantly, IBS does not cause structural damage to the intestines, nor does it increase the risk of colon cancer. However, its symptoms can overlap with more serious conditions, which is why proper diagnosis is essential.

The Emotional and Social Impact of IBS

IBS is often called an “invisible illness” because outwardly, sufferers may look perfectly healthy. Yet, the unpredictability of symptoms can take a heavy toll on mental and social well-being.

The anxiety of not knowing when a flare-up might occur can lead to avoidance of social situations, travel, or dining out. Some people even struggle with workplace challenges, fearing embarrassment or being misunderstood by colleagues. Over time, this can lead to feelings of isolation, frustration, and depression.

The stigma surrounding IBS also complicates matters. Digestive issues are still taboo in many cultures, leaving people reluctant to talk openly about their struggles. Raising awareness and normalizing these conversations is a critical step in supporting those who live with IBS.

Diagnosing IBS

There is no single test to diagnose IBS. Instead, diagnosis relies on clinical evaluation, symptom patterns, and the exclusion of other conditions.

The Rome Criteria

Doctors often use the Rome IV criteria, which define IBS as recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week in the last three months, associated with two or more of the following:

- Related to defecation

- Associated with a change in stool frequency

- Associated with a change in stool form or appearance

Rule-Out Testing

Because IBS symptoms can mimic other gastrointestinal conditions—such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or colon cancer—doctors may order tests like:

- Blood tests for celiac disease or anemia

- Stool tests for infection or inflammation

- Colonoscopy in patients with alarm features (such as rectal bleeding, unexplained weight loss, or onset after age 50)

The goal is to ensure that symptoms are not caused by more serious underlying disorders.

Treatment of IBS

There is no cure for IBS, but a wide range of strategies can manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Successful treatment often requires a personalized approach, as triggers and responses vary widely among individuals.

Dietary Management

Diet plays a central role in managing IBS. One of the most effective dietary strategies is the low-FODMAP diet, which reduces intake of fermentable carbohydrates like lactose, fructose, and certain fibers. Many patients experience significant relief after eliminating high-FODMAP foods.

Other dietary strategies include:

- Eating smaller, more frequent meals

- Reducing caffeine and alcohol

- Limiting fatty or highly processed foods

- Keeping a food diary to identify personal triggers

Medications

Depending on the type of IBS, medications may be prescribed:

- Antispasmodics to reduce cramping

- Laxatives for constipation-predominant IBS

- Antidiarrheal drugs for diarrhea-predominant IBS

- Low-dose antidepressants to reduce gut hypersensitivity and improve the gut-brain connection

- Probiotics to balance gut bacteria, though results vary

Stress Management and Psychological Therapies

Since stress and anxiety amplify IBS symptoms, therapies targeting the mind are highly effective. Options include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helps patients reframe negative thought patterns.

- Gut-directed hypnotherapy: A specialized form of hypnosis shown to reduce IBS symptoms.

- Mindfulness and meditation: Practices that calm the nervous system and reduce gut sensitivity.

Lifestyle Modifications

- Regular exercise to improve gut motility and reduce stress

- Adequate sleep to support hormonal and immune balance

- Hydration to aid digestion

The Role of Emerging Research

Science is continuously uncovering new insights into IBS. Exciting developments include:

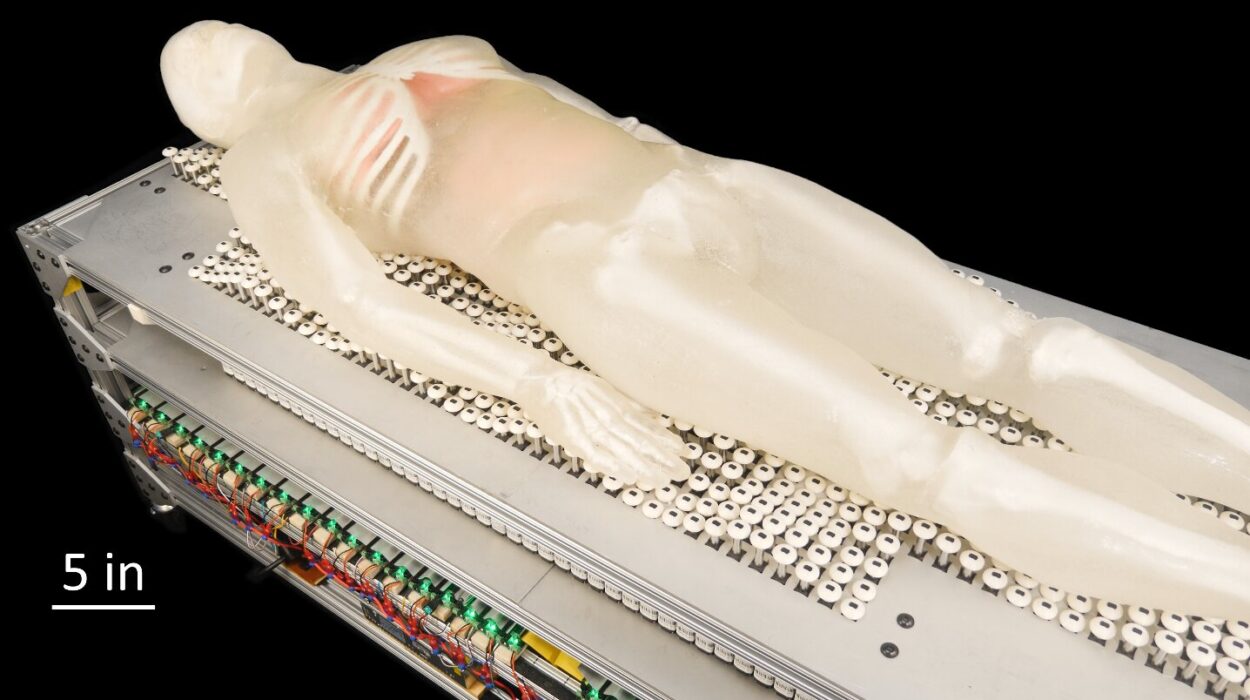

- Microbiome therapies: Researchers are exploring fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and targeted probiotics to restore balance in gut bacteria.

- Biomarkers: Efforts are underway to identify blood or stool markers that can simplify IBS diagnosis.

- Neuromodulators: Drugs that directly target the gut-brain axis are being developed to reduce hypersensitivity.

While these advances are promising, they also highlight how complex IBS truly is—a condition at the crossroads of biology, psychology, and environment.

IBS vs. Other Digestive Disorders

IBS is often confused with other conditions, particularly Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Unlike IBS, IBD (which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) involves structural damage, inflammation, and increased risk of cancer. IBS does not cause these complications, but the symptoms can overlap.

Similarly, celiac disease (an autoimmune reaction to gluten) must be carefully ruled out, as untreated celiac disease leads to intestinal damage, whereas IBS does not. The distinction is crucial because treatment approaches differ significantly.

Coping with IBS: Beyond Medicine

Living with IBS requires more than just medical management—it requires resilience, adaptation, and support. Many patients find empowerment through education, joining support groups, and developing self-care strategies. Open conversations with healthcare providers, family, and friends can help reduce the isolation and stigma often felt.

Some individuals embrace holistic approaches like yoga, acupuncture, or aromatherapy. While not universally proven, these practices can provide comfort and a sense of control. Ultimately, coping with IBS is about building a toolkit of strategies that address not just the gut, but the whole person.

The Human Side of IBS

Behind the statistics and medical definitions are real stories—people navigating careers, relationships, and dreams while managing an unpredictable digestive system. For some, IBS means carefully planning meals before big events. For others, it means declining invitations for fear of embarrassment. And yet, many show remarkable resilience, using humor, creativity, and determination to live fully despite the challenges.

Recognizing IBS as more than “just a stomach issue” is essential. It is a condition that demands compassion, understanding, and holistic care.

Conclusion: IBS as a Journey

Irritable Bowel Syndrome is not a single-path illness but a journey with twists, setbacks, and discoveries. It challenges the body, the mind, and the spirit, yet it also reveals the profound complexity of the human gut and its deep connection to our emotions and daily lives.

Science continues to advance, offering new tools and hope, but in the meantime, living well with IBS is about finding balance—through food, lifestyle, mental health, and community support.

IBS may not have a definitive cure today, but with knowledge, patience, and holistic care, individuals can reclaim control, reduce symptoms, and live vibrant, meaningful lives.