There’s a quiet virus that millions of women carry without ever realizing it. It doesn’t knock. It doesn’t announce its arrival with dramatic symptoms. Most of the time, it lingers in the background of your health story—unnoticed and underestimated. This virus is human papillomavirus, better known as HPV. And while it might not be the most glamorous topic for a conversation over coffee, it’s one of the most important ones every woman should have with herself—and her doctor.

HPV is not just one virus. It’s a family of more than 200 related viruses, some of which are passed from person to person through intimate skin-to-skin contact. You’ve probably heard of it in the context of cervical cancer or seen its name pop up on a pamphlet in your gynecologist’s office. But understanding HPV isn’t just about medical jargon and clinical statistics. It’s about knowing how it behaves, how it can affect your health, and how you can protect yourself and others. Knowledge, in this case, isn’t just power—it’s preventive care in its purest form.

Unpacking the Science: What Is HPV, Really?

Let’s strip the name down to its basics. “Human papillomavirus” sounds intimidating, but it essentially refers to a group of viruses that infect human skin and mucous membranes. Think of HPV like a large extended family—some relatives are benign and harmless, while others are a bit more troublesome. Some types of HPV cause common warts on your hands or feet, but those are not the ones we’re concerned with here.

The HPV types you hear about most in women’s health are the ones that infect the genital area, mouth, or throat. These are considered sexually transmitted infections, even though they don’t require traditional intercourse to spread. All it takes is skin-to-skin contact, and just like that, the virus finds its way in. The scary part? It’s incredibly common. Nearly every sexually active person—man or woman—will get HPV at some point in their lives. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that nearly 80 million Americans are currently infected with some form of HPV.

High-Risk vs. Low-Risk HPV: Why It Matters

Among the many strains of HPV, a handful are labeled as high-risk. These high-risk types don’t cause noticeable symptoms at first, but they have a sinister reputation for contributing to cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, anus, penis, and even the throat. Of all these, cervical cancer is the one most directly linked to high-risk HPV strains, particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, which are responsible for around 70% of cervical cancer cases.

Low-risk HPV strains, on the other hand, don’t usually lead to cancer. Instead, they might cause genital warts—small, flesh-colored growths that can appear on the vulva, cervix, vagina, or anus. They’re not dangerous, but they can be uncomfortable, unsightly, and emotionally distressing.

Here’s the twist: most HPV infections go away on their own. Your immune system is usually strong enough to clear the virus within a year or two. You might never even know you had it. But sometimes, the virus sticks around, quietly causing changes in your cervical cells over time. This is when it shifts from being a silent visitor to a potential health threat.

The Cervix Under Siege: How HPV Leads to Cancer

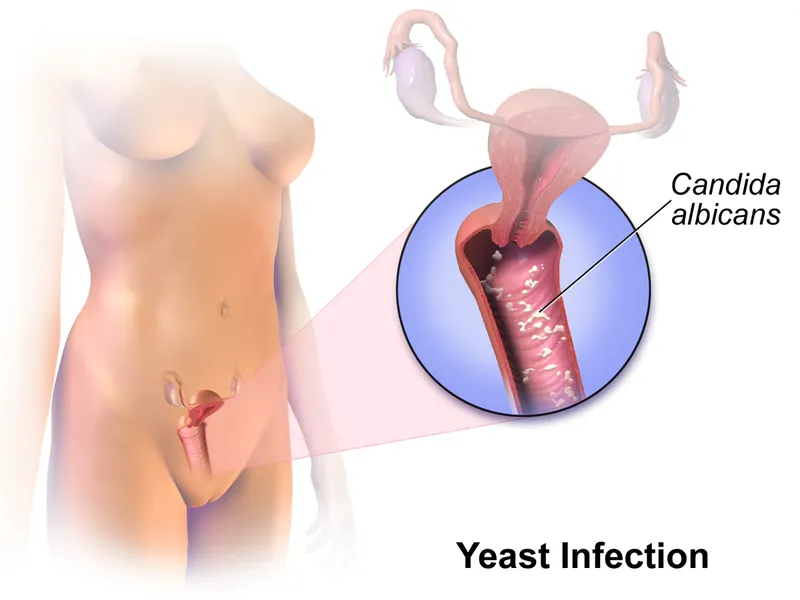

The cervix is a narrow passage that connects the vagina to the uterus. It plays a critical role in childbirth, menstruation, and reproductive health. But it’s also ground zero for HPV-related cellular changes. When high-risk HPV types infect the cervix, they can start to interfere with the normal cycle of cell growth and repair. Over months or years, this can cause precancerous lesions, areas where cells look abnormal but aren’t cancerous—yet.

If left unchecked, these abnormal cells can evolve into cervical cancer, a disease that still claims the lives of thousands of women each year, despite being one of the most preventable forms of cancer. The key to prevention lies in early detection, which is where routine Pap smears and HPV testing come in.

Testing and Screening: Your First Line of Defense

Let’s be clear: HPV testing isn’t something to fear. It’s something to embrace. The Pap smear, long a mainstay of women’s health, is designed to catch early cell changes on the cervix. When combined with an HPV test—which can detect the presence of high-risk HPV strains—it becomes a powerful tool for prevention.

Women aged 21 to 29 are typically advised to get a Pap test every three years. Once you hit 30, you may be offered co-testing: a combination of a Pap smear and an HPV test, which is recommended every five years if results are normal. In some guidelines, primary HPV testing—without a Pap—may even be used alone starting at age 25.

These screening tools don’t just save lives; they buy you time. Time to monitor changes. Time to treat precancerous conditions before they progress. And time to take charge of your own health narrative.

The Vaccine Revolution: A Shot at Prevention

If there’s one thing that’s dramatically shifted the landscape of HPV-related health issues, it’s the HPV vaccine. Introduced in 2006, the vaccine—known commonly by its brand name Gardasil—targets the most dangerous strains of HPV, including types 16 and 18, as well as others linked to genital warts.

Originally recommended for preteens (both boys and girls) starting at age 11 or 12, the vaccine can be given as early as age 9 and up through age 45. The idea is to vaccinate before exposure—before sexual activity begins—because the vaccine can’t remove HPV once you’ve contracted it.

But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth getting if you’re older. If you’re in your 20s, 30s, or even early 40s and haven’t been vaccinated, talk to your doctor. Even if you’ve already been exposed to one type of HPV, the vaccine can still protect you against others. It’s not a cure, but it’s a powerful form of armor.

The safety profile of the HPV vaccine is strong, and widespread vaccination has already led to significant drops in HPV infections and cervical precancers in many countries. This is public health success in real time.

HPV and Relationships: The Emotional Side of the Virus

One of the hardest parts of an HPV diagnosis isn’t physical. It’s emotional. Many women feel blindsided, confused, and even ashamed when they hear they’ve tested positive for HPV. But here’s the truth: HPV isn’t a sign of promiscuity. It’s a sign of being human.

Because the virus can lie dormant for years, it’s nearly impossible to know when or from whom it was contracted. You could have been exposed from a long-term partner or even in a previous relationship years ago. This latency makes HPV one of the most misunderstood STIs—and one of the hardest to talk about.

But talk we must. HPV doesn’t mean you’ve done anything wrong. It doesn’t mean your partner has cheated. And it doesn’t mean you can’t have a healthy, fulfilling sex life. It simply means your body is carrying a virus that most people carry at some point. Removing the shame removes the stigma. And when the stigma is gone, women can speak openly, ask questions, and seek the care they deserve.

Pregnancy and HPV: What You Should Know

HPV and pregnancy don’t usually mix in dangerous ways, but if you’re planning a family or are already pregnant, it’s worth understanding how the virus plays into prenatal care. Most women with HPV have normal, healthy pregnancies and deliveries. However, if HPV has caused cervical changes, your doctor may monitor you more closely.

Genital warts caused by low-risk HPV can grow faster during pregnancy due to hormonal changes. While rare, large warts can complicate vaginal delivery and might need to be treated before birth.

Importantly, HPV doesn’t affect your ability to conceive. And the risk of passing the virus to your baby is very low. Most infants exposed during delivery clear the virus on their own without any complications.

When HPV Doesn’t Go Away: Dealing with Persistence

For most women, the immune system kicks HPV to the curb within two years. But in some cases, the virus sticks around. When that happens, it’s known as persistent HPV infection, and it can increase your risk for cervical cancer.

The key word here is “risk.” Persistent HPV doesn’t mean you will get cancer, but it does mean you need to keep up with regular follow-ups and, if necessary, undergo procedures to remove abnormal cervical cells. Treatments might include cryotherapy (freezing the cells), laser therapy, or LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision procedure). These are highly effective in preventing cancer from ever taking root.

And remember, lifestyle plays a role. Smoking, a weakened immune system, and high stress levels can all increase the chance that HPV sticks around. Taking care of your overall health—eating well, exercising, and managing stress—might help your body fight the virus more effectively.

HPV Beyond the Cervix: Other Cancers to Know About

Cervical cancer gets most of the headlines when we talk about HPV, but it’s not the only cancer linked to this virus. HPV can also cause vaginal, vulvar, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers (cancer of the throat, tonsils, and tongue). While these are less common in women than cervical cancer, they are on the rise—especially head and neck cancers.

This underscores why HPV is not just a women’s issue. Men are also affected by HPV-related cancers, and both genders benefit from vaccination and safe practices. By understanding the full scope of the virus, we can push for better public health policies, more research, and greater awareness.

What Women Need to Take Away from All This

There’s a lot to digest when it comes to HPV. But here’s what it boils down to: don’t be afraid of it—be informed. HPV is common, often silent, and usually harmless. But in some cases, it can lead to serious health issues. That’s why screening, vaccination, and education are your best tools.

If you’re due for a Pap or HPV test, make the appointment. If you’re eligible for the vaccine, roll up your sleeve. If you’re navigating an HPV diagnosis, don’t do it alone. Talk to your doctor. Ask questions. Lean on your circle. You are not defined by a virus.

HPV doesn’t mean your body is broken. It means you’re part of a shared human experience. One where science, medicine, and community can come together to protect your health and your future.

The Future of HPV: Toward Eradication

There’s real hope on the horizon. With increasing vaccination rates and better screening methods, experts believe we could one day eliminate cervical cancer as a public health threat. Some countries, like Australia, are already on track to achieve this within the next decade.

But it will take all of us—women getting screened, parents vaccinating their kids, doctors staying informed, and health advocates pushing for equity and access. Eradicating HPV-related diseases is within reach. But only if we continue to talk about it, care about it, and fight for prevention.

So let this article be your invitation. To learn. To protect. To act. Because every woman deserves to know her body, her risks, and her power.